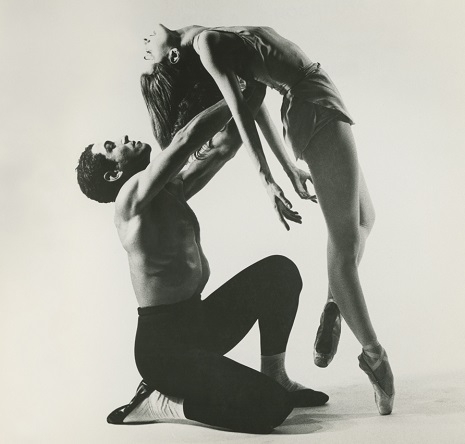

Francisco Moncion and Tanaquil Le Clercq from Jerome Robbins’ ballet ‘Afternoon of a Faun’

Too often Tanaquil Le Clercq’s contributions to the world of ballet are unfairly attributed to her husband and choreographer George Balanchine, the so-called “father of American ballet.” Balanchine infamously exercised a kind of droit du seigneur with the dancers under his direction, marrying them, divorcing them, cheating on them with their coworkers and even firing them when they rejected his advances. Tanaquil Le Clercq, or “Tanny,” as she was known affectionately, was no different. After admittance to Balanchine’s school of American Ballet at the age of 12, Tanny quickly became one of Blanchine’s favorite dancers,

At the age of 15 Tanny danced alongside Balanchine for a polio benefit show he choreographed—Balanchine played polio itself while Tanny played his victim, ultimately overcoming her illness at the end after children threw dimes at the stage. At 19, when Blanchine’s relationship with his former muse (and first American prima) Maria Tallchief had cooled, he took up with Tanny. When she was 21, they were married, with nearly 25 years between them. During the next few years, Tanny came to represent the ultimate “Balanchine ballerina,” her thin frame and long limbs belying a lean muscularity and a deft nimbleness (you can see some of her explosive footwork here, from the ballet Western Symphony with Jacques d’Amboise). Balanchine had always favored leaner bodies—prior to his influence ballerinas were often built more like gymnasts, more visibly muscular and compact. It was Tanny however, with her ultra-long legs and impossibly narrow sternum that represented the extreme of his vision.

Tragically, at the age of 27, Tanaquil collapsed onstage and was rushed to the hospital. She was diagnosed with polio; she had avoided vaccination, which she worried would leave her sore and unable to dance for a short time. Wracked by superstitious guilt, Balanchine spent years trying to train her body to dance again, but Tanny herself accepted the inevitable earlier than anyone. Eventually they split, and Balanchine went after his new muse, Suzanne Farrell. (She spurned him. He fired her.) Tanny eventually regained the use of her upper body and returned to teach ballet, using her long arms to demonstrate what should be done with legs. (There’s an amazing documentary of her life story you can stream from PBS.)

The performance below, “Afternoon of a Faun,” is not choreographed by George Balanchine, but by his colleague Jerome Robbins, who also vied for Tanny’s affections before her marriage to Balanchine—after her paralysis he wrote her love letters and photographed her extensively. Jerome Robbins never got the high society credit Balanchine did after leaving ballet to choreograph movies like West Side Story, but he’s clearly a genius of the genre. The performance is devastatingly erotic, with pelvic movements not considered “pretty” in classical ballet, and the use of Debussy, an impressionist, rather than a romantic of classical composer lends a dreamy ambiance to the entire affair. It’s filmed beautifully, and as Le Clercg and partner Jacques d’Amboise break the fourth wall to turn from the sparse stage setting to look at the camera, the audience is made to feel almost voyeuristic.