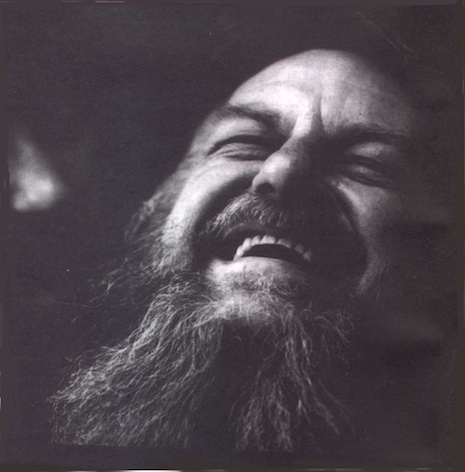

Cultural critic Mark Dery, whose erudite essays have appeared in the pages of the Atlantic Monthly, Washington Post, Village Voice and his own collections, The Pyrotechnic Insanitarium: American Culture on the Brink and Escape Velocity: Cyberculture at the End of the Century, returns with his remarkable biography of the comically sinister author and illustrator Edward Gorey. This delightful combination of biographer and subject has been praised in the New York Times, the New Yorker, at NPR Vogue and other prestige outlets. We’re pleased to present a short excerpt from Born To Be Posthumous: The Eccentric Life and Mysterious Genius of Edward Gorey (Little, Brown) at Dangerous Minds.

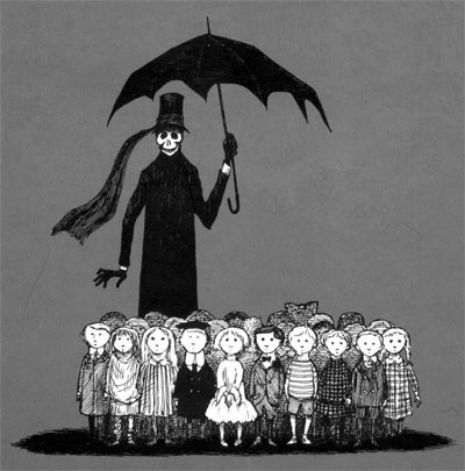

In the following excerpt from my just-published biography, Born To Be Posthumous: The Eccentric Life and Mysterious Genius of Edward Gorey (Little, Brown), I explore Gorey’s role, alongside Seuss and Sendak, in the postwar revolution in children’s books, a gleeful insurrection that killed off those insufferable, simpering Goody-Goodies, Dick and Jane, for good. In so doing, Gorey and other writer-illustrators reshaped American notions of kids lit and even childhood itself, making way for a more honest acceptance of the facts of life: divorce, death, racial tensions, queer desire. As well, the new wave slyly satirized not only the mainstream culture of the ‘50s and ‘60s but the conventions of children’s literature itself, many of which dated back to the cautionary tales and nursery-rhyme sermonizing of the Victorian era, when the children’s book as we know it was born. Whether Gorey’s work really was kiddie fare or arsenical treats for adults ironically disguised as picture books is still up for debate. Regardless, his influence is stronger than ever, identifiable at a glance in the YA novels of Lemony Snicket (A Series of Unfortunate Events) and Ransom Riggs (Miss Peregrine’s Home for Peculiar Children), the twee-goth movies of Tim Burton, and somber memoirs of “the miseries of childhood,” as Gorey put it, such as Alison Bechdel’s graphic novel Fun Home.

— Mark Dery

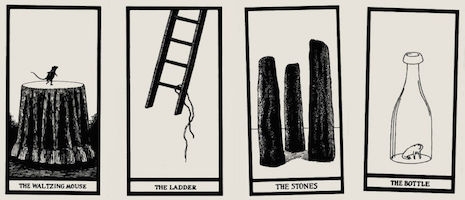

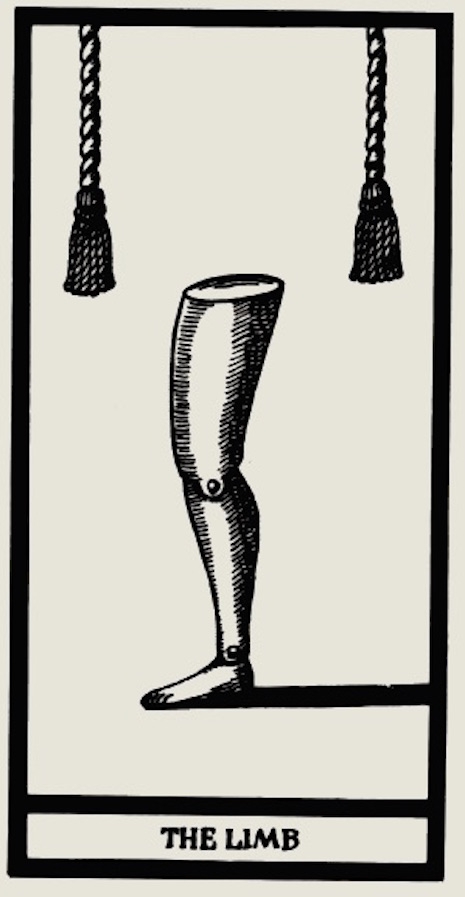

Nineteen-sixty saw the publication of Edward Gorey’s sixth book, The Fatal Lozenge, by the New York publisher Ivan Obolensky. Subtitled An Alphabet, The Fatal Lozenge was his first foray into the ABC genre. He would go on to perform variations on the abecedarium theme in six books, one of which, The Gashlycrumb Tinies, would become his best-known title. [They are, in chronological order, The Fatal Lozenge, The Gashlycrumb Tinies, The Utter Zoo, The Chinese Obelisks, The Glorious Nosebleed, and The Eclectic Abecedarium.]

The alphabet book is one of the oldest forms of children’s literature. Rhyming couplets, illustrated by woodcuts, aided memorization. Early examples wedded ABCs and Calvinist catechism. The New England Primer, ubiquitous in late-seventeenth-century America, is typical of the genre:

A In Adam’s Fall We sinnèd all.

B Heaven to find; The Bible Mind.

C Christ crucify’d For sinners dy’d.

D The Deluge drown’d The Earth around.

Gorey’s interest in the alphabet book was undoubtedly a byproduct of his interest in Edward Lear, well known for loopy abecedaria like “Nonsense Alphabet” (1845) (“P was a pig, / Who was not very big; / But his tail was too curly, / And that made him surly”). His library reveals a longstanding fascination with the form, with a predictable focus on the nineteenth century. On Gorey’s bookshelves, we find A Moral Alphabet (1899) by Hilaire Belloc, A Comic Alphabet (1836) by George Cruikshank, a Dover facsimile of The Adventures of A, Apple Pie, Who Was Cut to Pieces and Eaten by Twenty Six Young Ladies and Gentlemen with Whom All Little People Ought to Be Acquainted (circa 1835), and of course Lear in abundance.

At the same time, he couldn’t have been oblivious, as an illustrator working in commercial book publishing, to the waves Dr. Seuss was making in kid lit. Alphabet books were playing an important part in reshaping American ideas about childhood. Consider Seuss’s On Beyond Zebra! (1955), whose boy narrator dreams up a new alphabet for kids who think outside the Little Golden box (“In the places I go there are things that I see / That I never could spell if I stopped with the Z”). Or Maurice Sendak’s Alligators All Around (1962), in which “shockingly spoiled” reptilian protagonists throw tantrums and juggle jelly beans with abandon. These and other unconventional abecedaria celebrate Romper Room radicals who flout the rules. Seen in their cultural and historical context, they look like premonitions of the hippie era, with its worship of nonconformity and its elevation of the child to a cultural icon, not to mention its stoner humor and acid-soaked song lyrics.

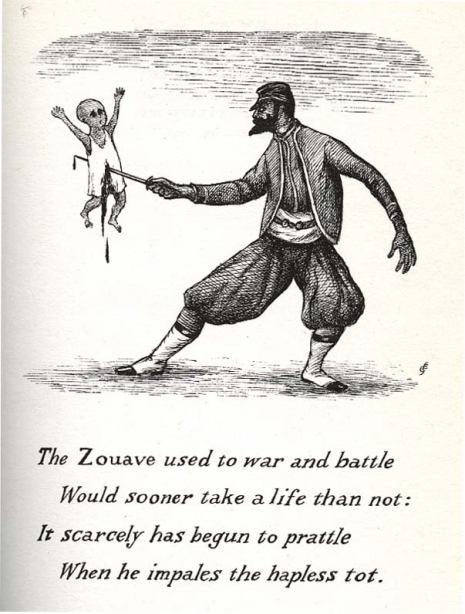

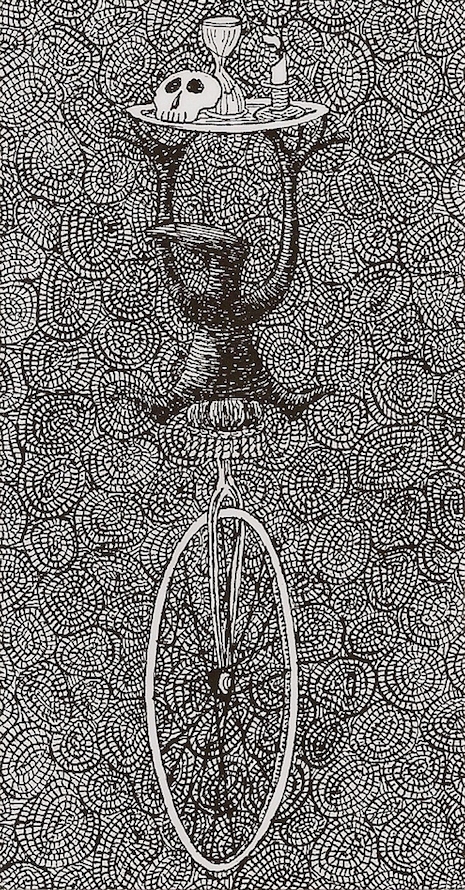

Though he seemed barely to notice the counterculture of the ’60s, beyond the Beatles, Gorey was in his own quietly perverse way more iconoclastic than Seuss or Sendak. In The Fatal Lozenge, as in The Listing Attic, his earlier book of macabre limericks, his combination of a children’s genre (in this case, the ABC book) with dark subject matter and black comedy is both mordantly funny and unsettling, especially when he crosses the line, as he occasionally does, into the “sick humor” of contemporaries such as the cartoonist Gahan Wilson. When an interviewer mentioned to Sendak that the grisly drawing of an infant skewered on the point of a Zouave’s sword in The Fatal Lozenge was the moment when Gorey went “down the road of no return as far as publishers were concerned,” Sendak quipped, “That’s why he was so loved. There’s never enough dead babies for us.”

The literary theorist George R. Bodmer places Gorey’s ironic, sardonic ABCs in the context of a postwar pushback, among children’s authors such as Seuss and Sendak, “against the limits of imagination, or the limits the outside world would impose on imagination . . .” In his essay “The Post-Modern Alphabet: Extending the Limits of the Contemporary Alphabet Book, from Seuss to Gorey,” Bodmer calls Gorey’s “anti-alphabets” a “sarcastic rebellion against a view of childhood that is sunny, idyllic, and instructive.” Gorey’s mock-moralistic tone satirizes received wisdom about the benignity of parents and other authority figures: a magnate waiting for his limousine “ponders further child-enslavement / And other projects still more mean”; two little children quail in terror at the sight of their towering, bearded uncle, for they “know that at his leisure / He plans to have them come to harm.” Yet Gorey also punctures the myth that children are little angels: a baby, “lying meek and quiet” on a bearskin rug, “Has dreams about rampage and riot / And will grow up to be a thug.” (The rug’s enormous, snarling head, with its bared fangs, is an omen of mayhem to come.)

Talking about The Fatal Lozenge in 1977, Gorey said, “This was a very early book and at that date I was not above trying to shock everyone a bit.” In that sense, his sixth book is so similar to his second that it might as well be called Son of Listing Attic. A good part of the book consists of the usual droll riffing on stock characters and situations borrowed from gothic novels, penny dreadfuls, Conan Doyle, and Dickens.

But just as clearly, there’s more going on in The Fatal Lozenge than enfant terrible-ism (“trying to shock everyone a bit”) or the larger trends identified by Bodmer: the bohemian backlash against the suffocating normalcy of the Eisenhower era and the growing resistance, led by Drs. Spock and Seuss, to outdated, repressive ideas about childhood and parenting. The recurrence of themes closer to home—the beastliness of babies, the depravity of the clergy (a nun is “fearfully bedevilled”), the furtiveness and shamefulness of homosexual desire, here associated with child molestation and even more monstrous perversions (“The Proctor buys a pupil ices, / And hopes the boy will not resist / When he attempts to practice vices / Few people even know exist”)—makes us feel, at times, as if we’re eavesdropping on a psychotherapy session. That these disconcerting images come to us in the reassuring wrappings of a children’s book makes The Fatal Lozenge even more disquieting.

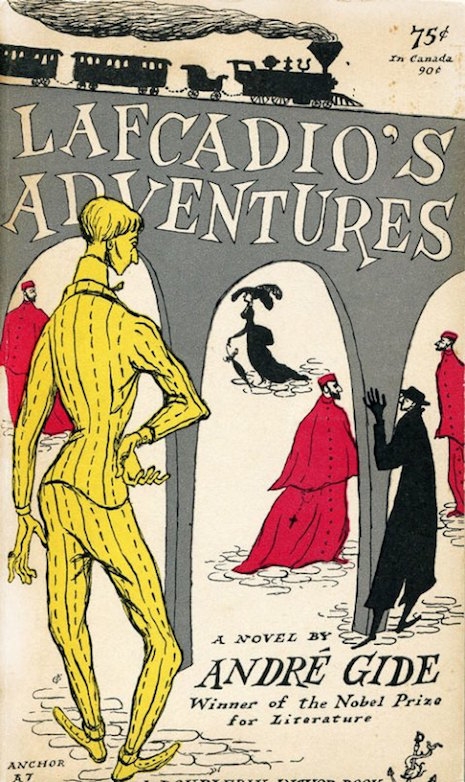

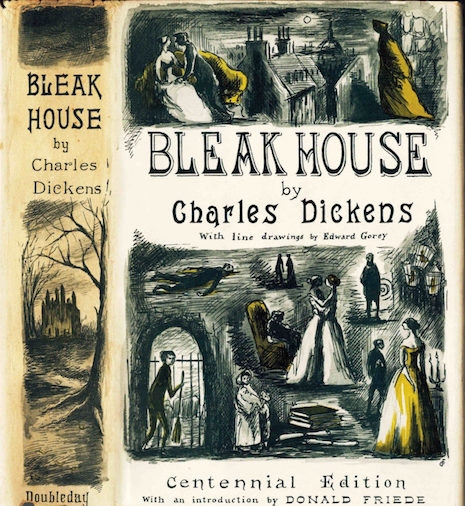

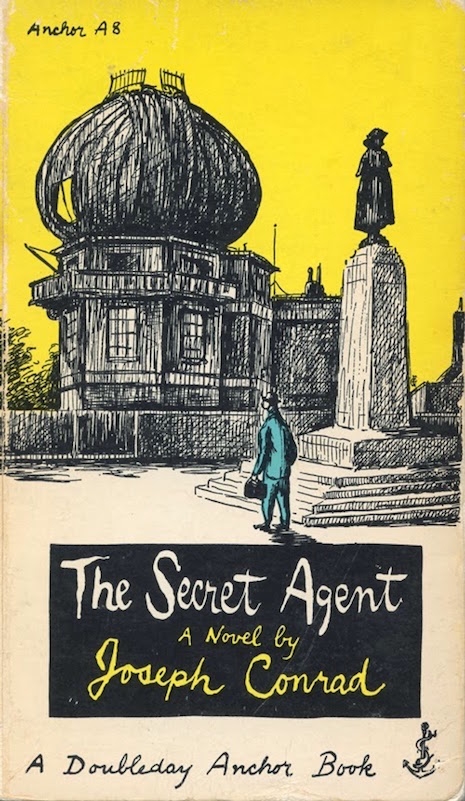

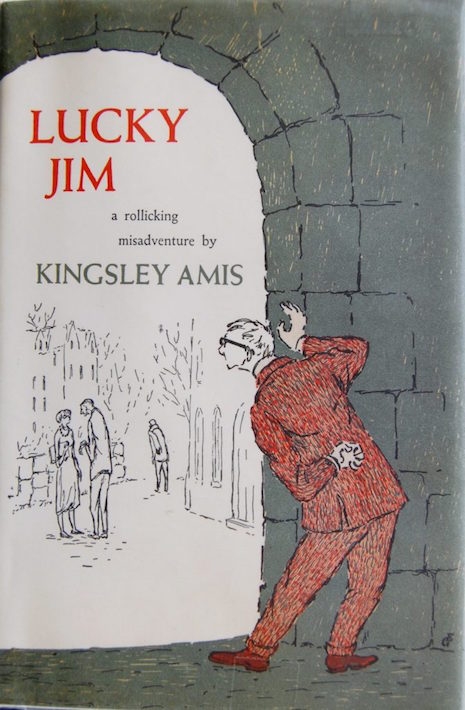

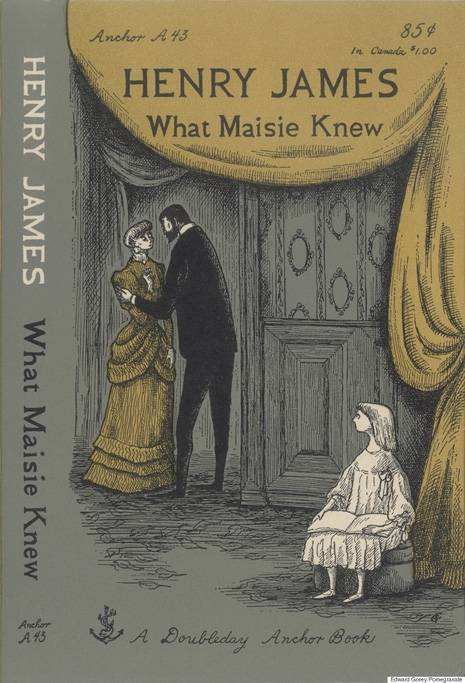

It’s precisely that insinuating knowingness that Sendak loved about Gorey’s little books. “They all had what appealed to me so much—aside from the graphics and the writing—[which] was the wicked sexual ambiguity that ran through all of it.” Even Gorey’s artlessly brilliant covers for Anchor Books, Doubleday’s tasteful paperback line, exhibited an arch wit, Sendal thought. “I remember a jacket he did for…a novel by Melville, Redburn. And the jacket summed up completely the kind of confused homosexuality of that novel….So erotic and yet so simple. You can look at it any way you like. . . . [H]e buried a lot of information about himself in the art.”

More after the jump…