Top fact: Jules Verne is the most translated French author ever.

Second slightly more impressive fact: Jules Verne is the second most translated author in the world, not too far behind Agatha Christie but ahead of William Shakespeare.

In the English-speaking world, Monsieur Verne may still have the reputation as a children’s author whose best-selling books have provided prime material for a lot of Hollywood movies but in truth, Jules Verne is the “Father of Science-Fiction.” Verne produced his best-known works like Journey to the Center of the Earth (1864), Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea (1870), and Around the World in Eighty Days (1873), long before his nearest rival H.G. Wells ever considered putting pen to paper.

At school, Jules Verne was the type of author whose novels were doled out during reading class and awarded (if you were lucky) at prize givings for academic excellence. That kind of thing. There was something wholesome about Verne and to an extent, H.G. Wells. A real belief that reading these authors inspired the right kind of enquiring mind—one driven by an interest in understanding the world through scientific investigation. Which was kinda strange as our teachers were a bunch of Christian Brothers whose remit was to instill the fear of God, teach some useful education, and offer the requisite religious instruction to live a good Catholic life.

Well, I suppose one out of three isn’t bad for the effort.

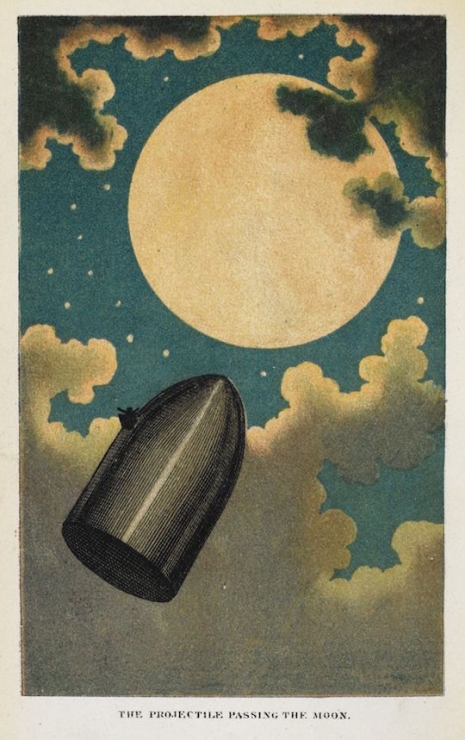

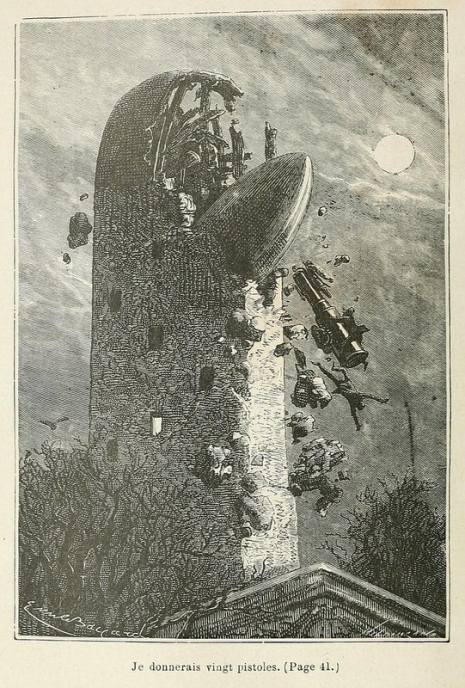

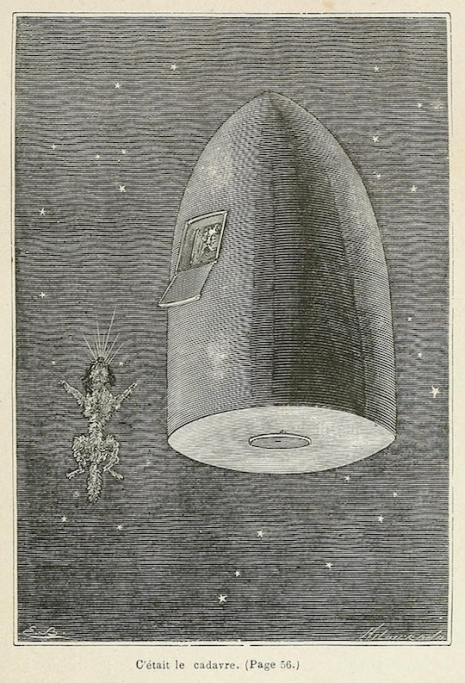

This was when America was firing rockets at the Moon, something that made Verne seem prescient and relevant in a way figures like Nostradamus never do. I’d read From the Earth to the Moon and thought it interesting but slightly disappointing as (unlike say Wells’ The First Men in the Moon with its insectoid creatures the Selenites) the book was mainly concerned with the scientific practicalities facing the Baltimore Gun Club in their ambitions (and rivalries) to send a rocket to the Moon. I was far more impressed by the follow-up novel Around the Moon which continued the adventures of the first three astronauts—Impey Barbicane, Captain Nicholl, and Michel Ardan (along with their dog)—who were fired in a bullet-shaped rocket from a giant cannon—the Columbiad space gun—up into space.

Verne’s novels were highly entertaining and his ideas always seemed feasible. One book, Paris in the Twentieth Century, which was written in 1863 but not published until 1994 having languished in locked bronze safe for almost a century, described the very world in which we live today, as Oliver Tearle notes in his compendium The Secret Library:

[Paris in the Twentieth Century] had been written in 1863 but [was] set in the then far-off future world of 1960. It described a world in which people drive motorcars powered by internal combustion and travel to work in driverless trains. Their houses are lit by electric light. They use fax machines, telephones and computers, and live in skyscrapers furnished with elevators and television. The criminals are executed using the electric chair. Greek and Latin are no longer widely taught in schools, and the French language has been ‘corrupted’ by borrowings from English. People shop in huge department stores, and the streets are adorned with advertisements in electric lights. Money has become everyone’s god. The novel also describes a tall structure in Paris, an electric lighthouse that can be seen for miles around. This was in 1863; the Eiffel Tower would not be built until 1889.

Similarly, many of the ideas in Around the Moon are scientifically possible and uncannily descriptive of how an Apollo misison to the Moon would return to Earth—jet rockets for thrust and a landing in the sea. The artist Émile-Antoine Bayard was tasked with illustrating Verne’s novel and he produced a set of images which are rightly described as “arguably the very first to depict space travel on a scientific basis.”

Take off with more incredible illustrations from Verne’s ‘Around the Moon,’ after the jump…