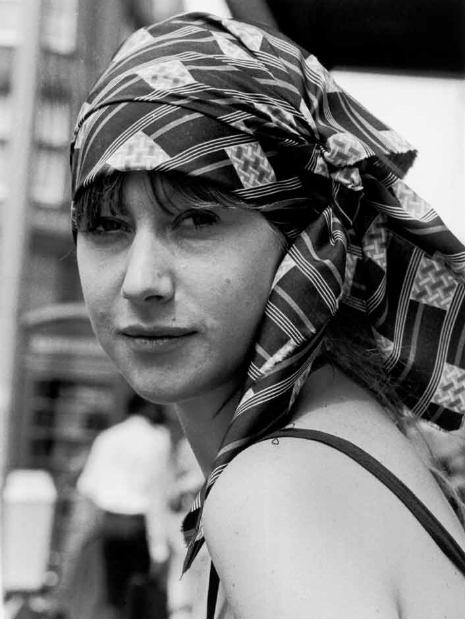

Helen Mirren interviewed about her starring role as Maggie, a rock singer, in David Hare’s play Teeth ‘n’ Smiles, and its revival at the Wyndham’s Theater in London’s West End, 1976.

The play related the events of a May Ball at Jesus College, Cambridge, in 1969, when a fading rock band are hired to perform to the College’s indifferent students, leading to a meeting of two very different worlds, which ends with Maggie burning down the marquee, in which the band played. Teeth ‘n’ Smiles originally opened at the Royal Court in 1975 to some mixed reviews for its author, but generally positive reviews for its star.

With its revival on the West End, Helen appeared on BBC’s news and current affairs show Tonight, where she was asked by interviewer Donald MacCormick, whether she thought the production would have a good West End run?:

‘You never can tell with the West End. You have a play here that is not usual West End material, in the sense that it’s not middle aged and middle class, particularly. It’s got a lot of swear words in it, a lot of very loud music. On the first public preview quite a lot of people walked-out, quite early on in the play when the first music takes place as it was too loud.’

Dame Helen was attracted to the central role of Maggie because the character had “balls” though she did find the part “worrying” as it made her feel “unattractive.” She explained this here and in other interviews given at the time:

I’m very like Maggie in many ways, only she’s much more ballsy and gutsy than me. I endorse most of what Maggie says, in fact in many ways it’s difficult to talk about her because I feel so close to her…

When I was first offered the part I was so scared. I’ve never wanted to play a part so much since I played my first part when I was seven years old [Gretel]. I get very bored going to the theatre now. I’d much rather go to rock concerts [JJ Cale, Dr John and Led Zeppelin are among her favourites]. So when I was offered the part of Maggie, a singer, well, I’m not a natural audience, I’m a performer, I had to do it. Of course I felt scared about the singing, I love singing but I can’t sing. [Nick Bicat, music director for the production, says she can sing ‘because she’s herself and very brave’.] (Time Out, 1975, parentheses in the original)

There aren’t many good parts for actresses. Maggie is a good strong part and that’s quite rare in modern theatre. So I like it for that. I don’t like it because it gets to me in a funny sort of way. Perhaps too close to sides of me I don’t much like. But it just makes me feel unattractive.

… Maggie’s doing it [struggling with a boring middle-class background] in one way. I don’t think that’s the only way to do it, possibly. But I’ve always had this sneaking admiration for people who go to the extremes of energy and wit. They’re terribly, horribly destructive often, but there’s something really fascinating and very lovable about them. I find it very difficult to let go. I mean I find it practically impossible to let go. I just get very sulky instead. I don’t think I can do a Maggie at all. I’m too self-conscious.

… When I played Miss Julie, it was the same cathartic experience, because you let it go. You let it all come out without ever actually committing yourself personally – although I do try to commit myself personally as much as possible on stage and try to make it as real and present as possible. (NME, 1976)

Teeth ‘n’ Smiles was very much an important part of its day, reflecting a time when London’s theaters were filled with old school socialist machismo—where male writers (David Hare, Howard Brenton, David Edgar, Trevor Griffiths, amongst others) dealt with the issues of politics and society, often with little recourse (or collaboration) to women.

Ms. Mirren has thankfully gone on from strength-to-strength, to become one of England’s greatest actresses.

Previously on Dangerous Minds

Bugger the Natives: The Trial of Howard Brenton’s ‘The Romans in Britain’

With thanks to NellyM