It was John Willett’s review of William S. Burroughs Naked Lunch, in the Times Literary Supplement, that led poet and writer, Dame Edith Sitwell to make her famous statement about the book, in 1963.

Willett was a writer, critic and, most importantly, translator of Bertolt Brecht’s plays. His translations so impressed the playwright that it led to their collaboration on the Berliner Ensemble’s historic 1956 London season. Yet, for such a seemingly radical critic and writer, Willett hated Naked Lunch and made his thoughts well known in a review headlined “Ugh!”:

“[Naked Lunch]...is not unlike wading through the drains of a big city . . . [It features] unspeakable homosexual fantasies . . . ...such things are too uncritically presented, and because the author gives no flicker of disapproval the reader easily takes the ‘moral message’ the other way…..If the publishers had deliberately set out to discredit the cause of literary freedom and innovation they could hardly have done it more effectively…”

Appearing not long after the controversial trial and publication of D. H. Lawrence’s infamous Lady Chatterley’s Lover in 1960, it seemed to many of England’s older and moneyed class that their world was under very real threat from the Barbarians at the gates.

One such figure, was Dame Edith, who upon reading Willett’s review fired off the following missive to the TLS:

To the Editor of the Times Literary Supplement

[published 28 November 1963]

Sir,

I was delighted to see, in your issue of the 14th instant, the very rightminded review of a novel by a Mr. Burroughs (whoever he may be) published by a Mr. John Calder (whoever he may be).

The public canonisation of that insignificant, dirty little book Lady Chatterley’s Lover was a signal to persons who wish to unload the filth of their minds on the British public.

As author of Gold Coast Customs I can scarcely be accused of shirking reality, but I do not wish to spend the rest of my life with my nose nailed to other people’s lavatories.

I prefer Chanel Number .

Edith Sitwell, C.L.

What Dame Edith failed to grasp was that to a generation of young, free-thinking individuals, this letter was the perfect encouragement to go and buy the book.

Though Mr. Burroughs and Mr. Calder had made no small an impression at the Edinburgh Festival in 1962 (though arguably upstaged by the legendary spat between Communist poet Hugh MacDiarmid and Beat writer Alexander Trocchi), it is fair to say, this letter was amongst the best publicity they could have had for Naked Lunch.

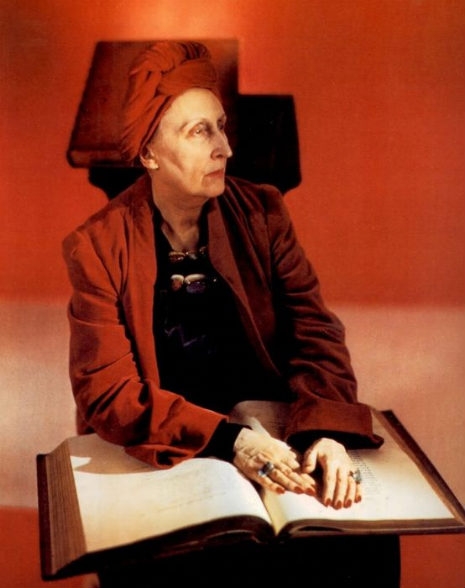

Edith Sitwell is sadly neglected today, and her poetry, biographies, and one experimental novel are now mainly left to the reading lists of academics. Yet once, Edith and her brothers Osbert and Sacheverell, were the English Avant Garde—but time, fashion, politics and a World War soon usurped their position.

The poem mentioned in her letter, Gold Coast Customs (1930), was Sitwell’s own (almost Ballardian) tale of the horrific barbarism lurking beneath the artificiality of civilized humans in the city of London.

The following clip is of Dame Edith discussing her life, her parents and Marilyn Monroe, in 1959.

Previously on Dangerous Minds

‘Whaur Extremes Meet: A portrait of the poet Hugh MacDiarmid