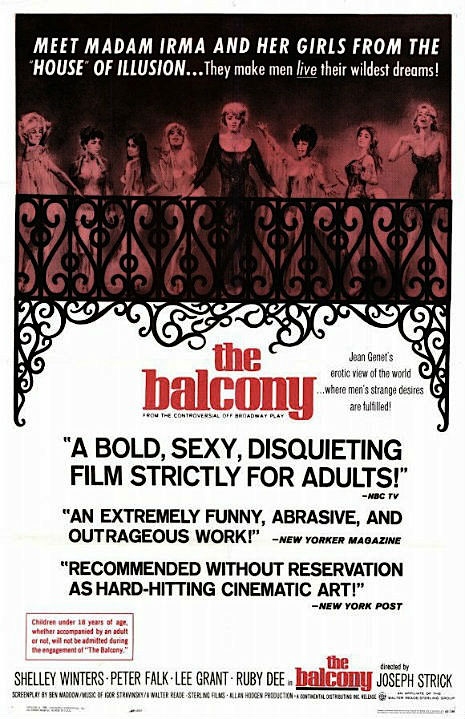

The Savage Eye was an early example of American cinema vérité that began as a film project worked on (over several years at weekends and days off) by three friends Ben Maddow (famed and award-winning screenwriter of Asphalt Jungle amongst many others), Sidney Meyers (radical film-maker and documentarian), and Joseph Strick (successful businessman and ambitious film-maker). Their movie mixed social documentary and drama that told the story of one woman’s (low) life in big, anonymous, brash, modern Los Angeles. It became a major hit at the Edinburgh Festival and won the trio a BAFTA—the equivalent of a British Oscar—in 1960. Encouraged by the film’s success, Strick sought out another project to work on.

He tried and failed to option James Joyce’s Ulysses, a project he had long cherished, though he would eventually film Ulysses with Milo O’Shea in 1967, and later produce and direct the big screen adaptation of Joyce’s A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man with Bosco Hogan and John Gielgud in 1977. Having failed on a first attempt with Ulysses, Strick approached Friedrich Dürrenmatt to option his play The Visit—in which a woman offers her home village money and success at the cost of killing her ex-boyfriend—but was also knocked back. He then approached Jean Genet and asked to option the film rights to his highly controversial play The Balcony. This time he was successful.

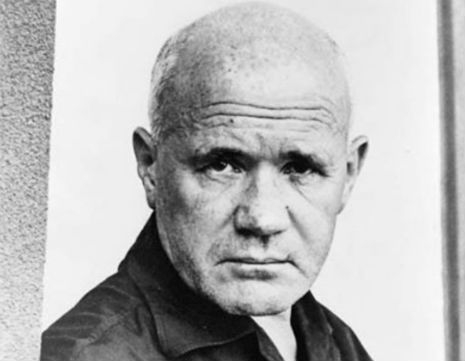

Jean Genet.

The Balcony is a brilliant and often disturbing drama, hailed as either the play that re-invented modern theater or the first great piece of French Brechtian theater—take your pick. Set in a high-class whorehouse situated in some unnamed city during an apparent bloody revolution, the play works as a metaphor for the different classes and corrupt structures of society. Genet wrote the first version of The Balcony (and a first version of The Blacks) in the spring and summer of 1955. Over the next ten years, Genet constantly wrote and rewrote The Balcony and between 1955 and 1961 he published five different versions. (There are some—like the play’s editor Marc Babezat—who believe Genet destroyed the script through his incessant revisions.)

In his introduction to the first version of The Balcony, Genet explained the drama’s story:

This play has as its object the mythology of the whorehouse. A Police Chief is infuriated, chagrined, to notice that at the ‘Great Balcony’ there are many erotic rituals representing various heroes: the Abbe, the Hero, the Criminal, the Beggar—and others besides—but alas, never he Police Chief. He struggles so that his own character will finally, through an exquisite act of grace, haunt the erotic daydreams and that he will thereby become a hero in mythology of the whorehouse.

Though Genet claimed he had no interest in films (“Cinema does not interest me”), he agreed to Strick’s offer to produce a movie version of The Balcony. Edmund White in his biography of Genet described the original meeting between French playwright and American film-maker:

Strick first encountered Genet in Milan, where Genet had reserved rooms in two different hotels ‘in case he had to reject my idea—he’s that sensitive,’ said Strick. Genet had seen one of Strick’s earlier films The Savage Eye, the story of a sad, recently divorced woman and her view of the seedy side of California life. Genet instructed Frechtman to speak to Strick for him: ‘Tell him that a lot of the images in his film touched me, but that the plot construction, the under-pinning appeared to me very weak. He doesn’t prove to us that this woman has changed at the end of the film. Now, a film adapted from The Balcony needs a very solid structure. Who will provide?’

While Strick stayed in the luxurious Hotel Negresco, Genet preferred a ratty hotel he called the Horresco. He was clean and neat but always dressed in the same corduroy trousers, turtleneck sweater and black leather jacket. Genet wrote a long treatment, a detailed description of the action without dialogue. Two stumbling blocks were the character Roger’s self-castration, and the whole end of the play, which is not well integrated with the preceding scenes. In the final version the castration was indeed removed. Genet worked four hours a day. Strick wanted Genet to do a shooting script and promised to follow every shot, but Genet didn’t want to invest any more time in the project. He latter told Marianne de Pury that he found the collaboration very irritating. He was still working on The Screens. He did accept, however, the idea that The Balcony should take place in a film studio and not a whorehouse.

Peter Falk as the Police Chief and Shelley Winters as Madame Irma in Strick’s ‘The Balcony’.

Ben Maddow was then employed to write the final script. The movie was then shot a very low budget, with the actors all working for minimum wage. Strick originally wanted Barbara Hepworth as Madame Irma, but she refused working for a minimum fee. Strick therefore approached the Hollywood star Shelley Winters to play the madame. Peter Falk, in only his second movie, agreed to play the Chief of Police, while future Mr. Spock, Leonard Nimoy played the role of Roger. Ruby Dee reprised her stage role as one of the prostitutes. Though considerably tamer than the Genet’s play, Strick still manages to maintain much of the play’s integrity. However, critics were mixed on the film’s release, with some papers, like The New York Times—quelle surprise—hating it. Watching it now, Strick made a bold and brave venture of a difficult and powerful drama.

+lobby+card_465_357_int.jpg)