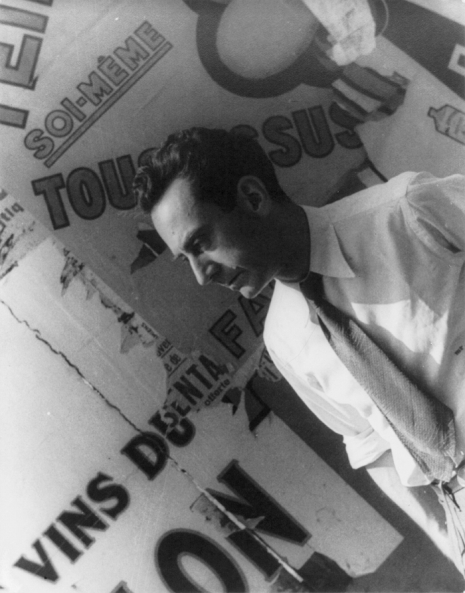

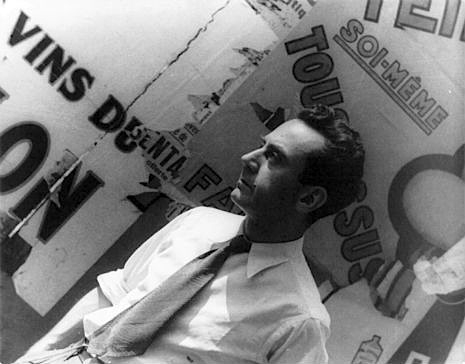

Man Ray never talked much about his childhood or his family background. He didn’t think it was important or relevant to his life as an artist. He never even acknowledged his real name, Emmanuel Radnitzky. He was born in Philadelphia to Max and Minnie Radnitzky in 1890, the eldest of four children (two brothers, two sisters). His father was a tailor and when the family moved to Brooklyn in 1897, Max changed their surname to “Ray” as he was concerned over the rise in anti-semitism in New York. This name-shortening led Emmanuel, or Manny as he was called, to edit his first name to “Man.”

Ray had ambitions to be an artist. At first, his parents weren’t too happy about their eldest son opting out of the family business but decided to let Ray follow his own course going so far as to rent him a studio/room in which to work. He became a successful commercial artist and furthered his ambitions by enroling in art classes.

In 1912, Ray saw the Armory Show, the “infamous” exhibition of paintings and sculptures by new “modern” artists like Cezanne, Matisse, Picasso, and Duchamp which caused considerable controversy and outrage among New Yorkers. It was Duchamp’s “Nude Descending a Staircase, No. 2.” that fired Ray’s imagination to the possibilities of art. The two met and Ray and Duchamp and became friends. Together they formed the New York Dada Group—a loose gathering of “anti-art” artists. Inspired by work he had seen at the Armory Show, Ray also started painting cubist pictures and began to experiment in different forms and techniques.

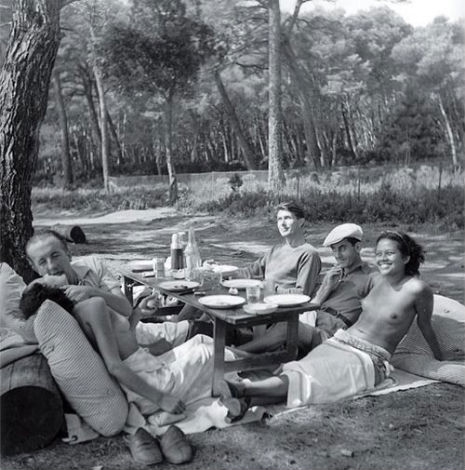

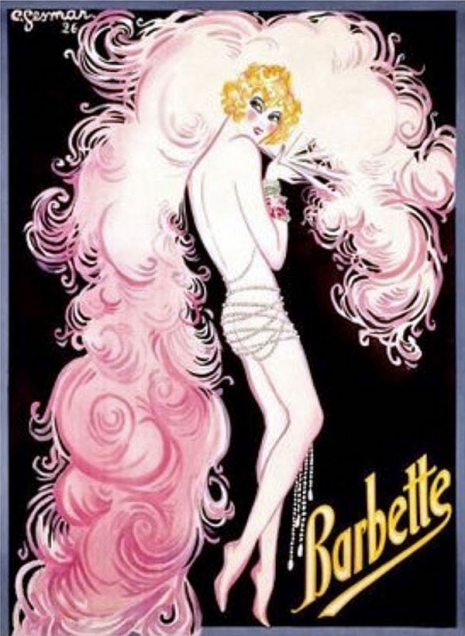

But it was when Ray moved to Paris in 1920, that he truly began his career as a photographer and filmmaker. He lived in the artists’s quarter of Montparnasse, and soon fell in love with the famous model, singer, budding actress and well-known Bohemian Kiki de Montparnasse (aka Alice Prin). Kiki became Man Ray’s lover and muse, who he began to photograph, which in turn led him to his first experiment as filmmaker Le Retour à la Raison in 1923.

Man Ray aligned himself with the Cinéma pur movement, which focussed on taking film away from narrative and plot and returning it to movement and image. Its proponents were René Clair, Fernand Léger, Hans Richter and Viking Eggeling, amongst others, and their short films were the beginnings of what is now described as “Art Cinema.”

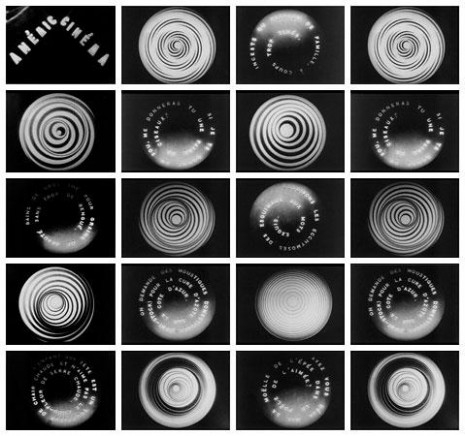

Adhering to Cinéma pur‘s loose manifesto, Man Ray’s early films, Le Retour à la Raison (Return to Reason) in 1923 and Emak-Bakia (Leave me alone) in 1926, focussed on creating startling textural patterns through the representation of objects within rhythmical loops. The experimental techniques of Le Retour à la Raison was repeated and developed in Emak-Bakia. Many of the techniques Man Ray developed (double exposure, Rayographs and soft focus) were later co-opted by animators and filmmakers during the 1940s to 1960s.

Moving away from Cinéma pur, Man Ray experimented with narrative structures and dramatic sequences. In L’Étoile de mer (The Sea Star) (1928), he told the story of two lovers from the point of view of an (underwater) starfish. The story had been inspired by a friend who kept a starfish in a jar by their bedside, and was written by the poet Robert Desnos, who died in a concentration camp in 1945.

In 1929, Ray started work on his longest film Les Mystères du Château de Dé (The Mysteries of the Chateau of Dice). This time Ray presented the story of two young travelers who visit the Villa Noailles in Hyères—the home of husband and wife Charles and Marie-Laure de Noailles, the patrons of Picasso, Cocteau, Dali, and many of the Surrealists—with its Cubist garden designed by Gabriel Geuvrikain. The film is surreal, dreamlike, and relies more on atmosphere and suggestion than any real narrative form. In large part it was “inspired by the poetry of Stéphane Mallarmé” in particular, his poem Un Coup de Dés Jamais N’Abolira Le Hasard (A Throw of the Dice will Never Abolish Chance), written in 1897. This poem was published over twenty pages in various typeface and structure. It contained early examples of Concrete Poetry, free verse and presented highly innovative graphic design that would later influence Dada. Some Surrealists criticized Ray’s films for not having enough narrative but Ray was more interested in creating something that didn’t relate to what had gone before. In the same way, he never acknowledged his own history before he became Man Ray.

Previously on Dangerous Minds:

‘The Cameraman’s Revenge’ - Wladyslaw Starewicz Surreal Stop-Motion Animation from 1912

‘Les Avortés’: Surreal short film with music by Captain Beefheart, from 1970

Boys and girls come out to play: The strange, surreal, and phantasmagorical world of Jaco Putker

Meet the Cubies: Modern Art spoof from 1913

Dream of Venus: Inside Salvador Dalí‘s spectacular & perverse Surrealist funhouse from 1939

The Autoerotic Art of Pierre Molinier

_thumb_465_348_int.jpg)