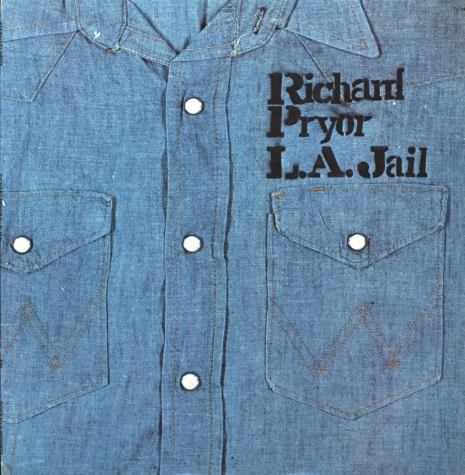

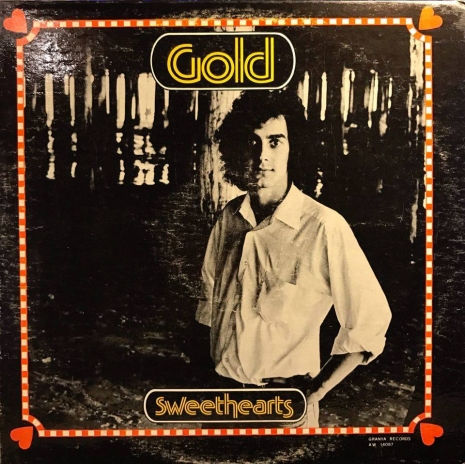

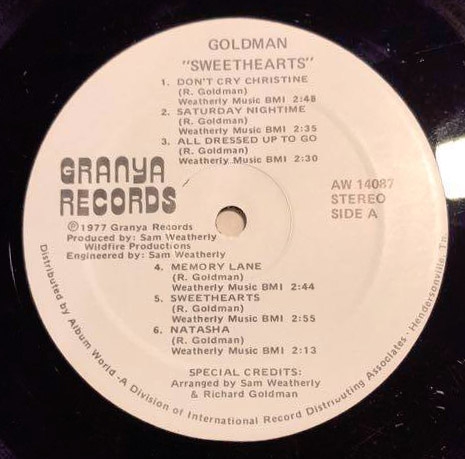

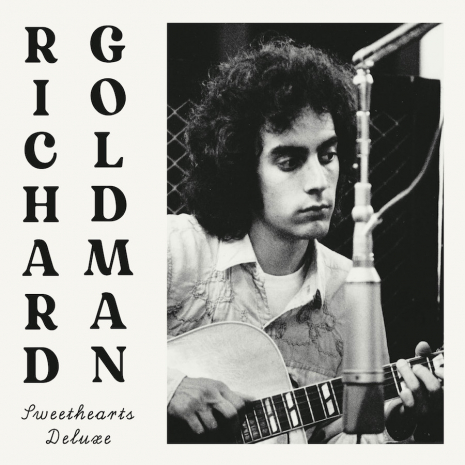

In April 2017, we told you the incredible story of the talented singer/songwriter Richard Goldman and the LPs of his material that were put out without his knowledge. Both records were released as part of tax shelter deals in 1977. The albums are testaments to his knack for writing and performing clever, catchy songs, but in addition to not being asked if his works could be used on those records, Richard received no financial compensation. Forty-plus years later, these injustices are finally being righted with Numero Group’s issuing of Sweethearts Deluxe, the first authorized collection of Richard’s recordings that were included on tax shelter albums.

To celebrate the release, which is out today, we’re reposting part one of our 2017 article on Richard Goldman and the shady world of “tax scam records.”

*****

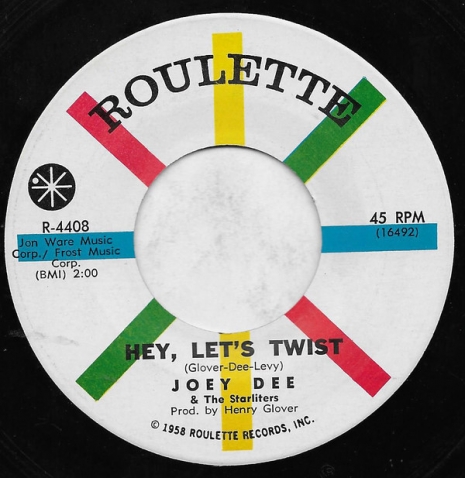

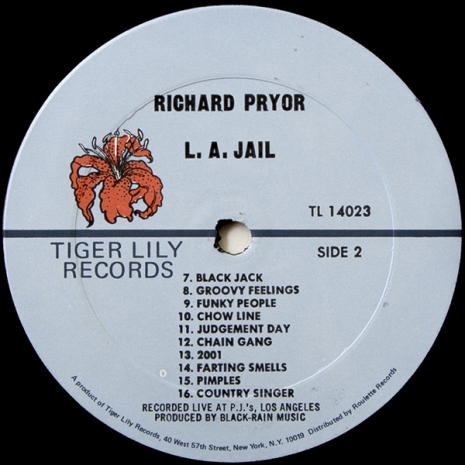

“Tax scam records” is a term that was coined by collectors to identify albums that are believed to have been manufactured for the sole purpose of—get this—losing money. From around 1976 until 1984, a number of record labels were established as tax shelters, with investors putting their money into albums. A financier would invest, say, $20,000 in an LP, and if it tanked, the backer could claim a loss on their taxes, based on the assessed value of the master recording. Technically, the practice was legal, but to maximize the write-off, the appraisal was often grossly inflated—as high as seven figures.

The I.R.S would come to question the legitimacy of some of these labels, and accuse those promoting shelters that focused on tax benefits—rather than the music being bankrolled—of perpetuating fraud.

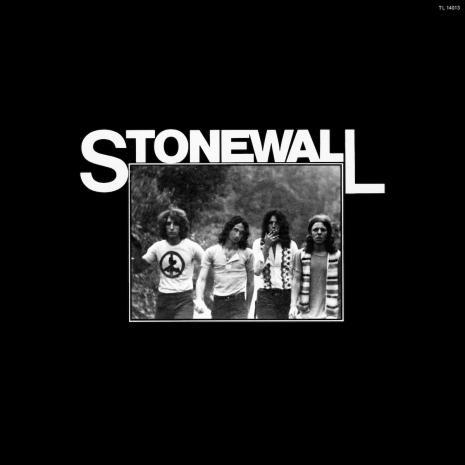

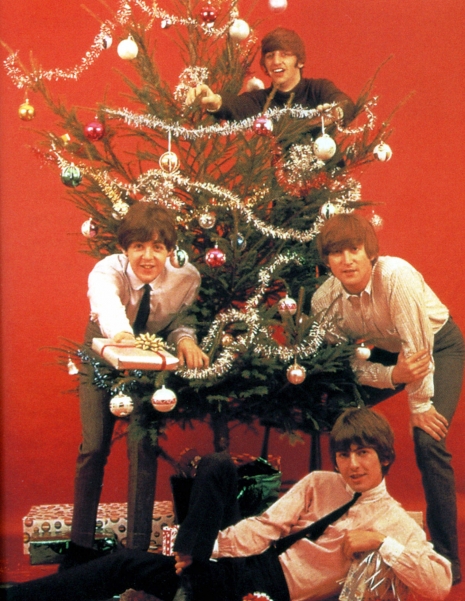

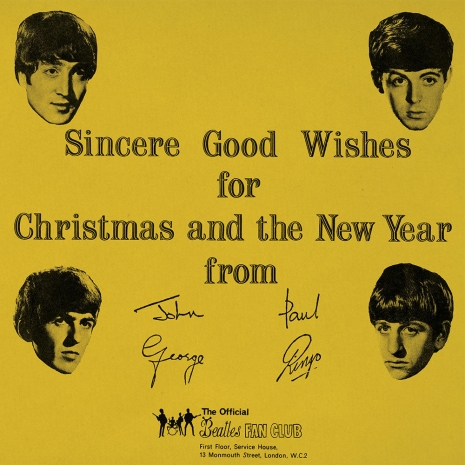

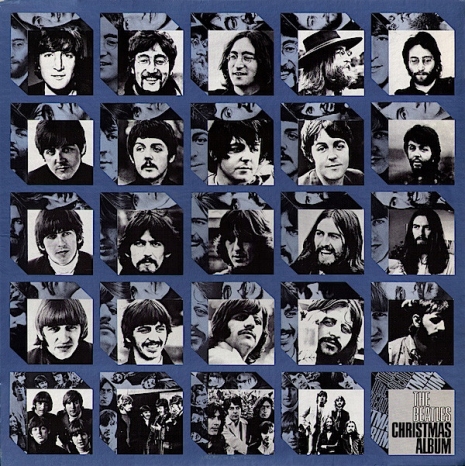

Anything was seemingly fair game for a tax shelter album, including LPs previously issued as private press records, demo tapes by aspiring artists, and studio outtakes by name acts. Some labels were so brazen, they released albums using material by groups as big as Led Zeppelin and the Beatles.

Album of Beatles Christmas messages, 1981

Another issue that caught the attention of the I.R.S., was how little to no money was put into marketing these releases. Over time, collectors came to realize that relatively few copies of individual tax shelter albums had made it into stores. It’s believed that most of the LPs went directly to a warehouse or were simply destroyed. Many of these records are so scarce that only a handful of copies are known to exist.

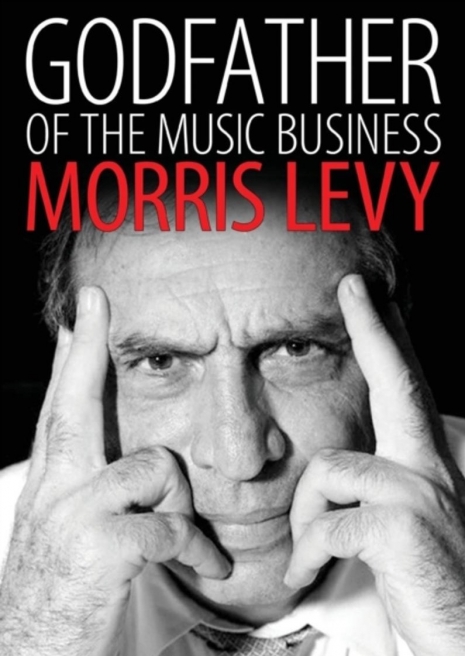

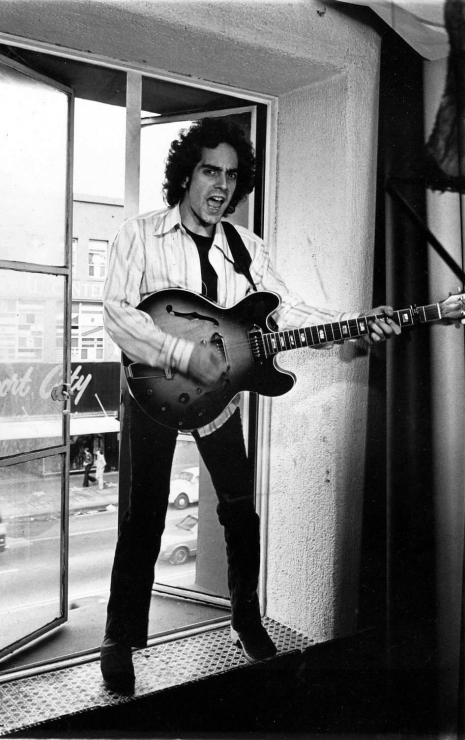

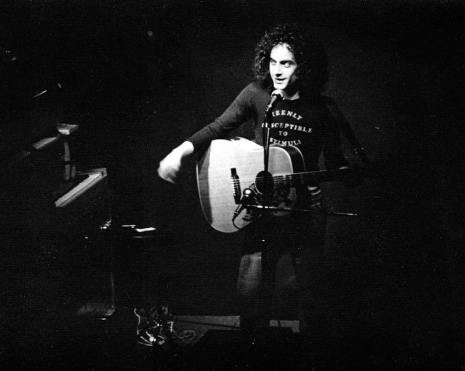

Sometimes the artists knew about the release and were compensated, but more often than not, they had no idea. The singer-songwriter Richard Goldman is an artist in which the latter applies. Though getting ripped off isn’t unusual in the music business, his story is a fantastic one—even in the strange universe of “tax scam records.”

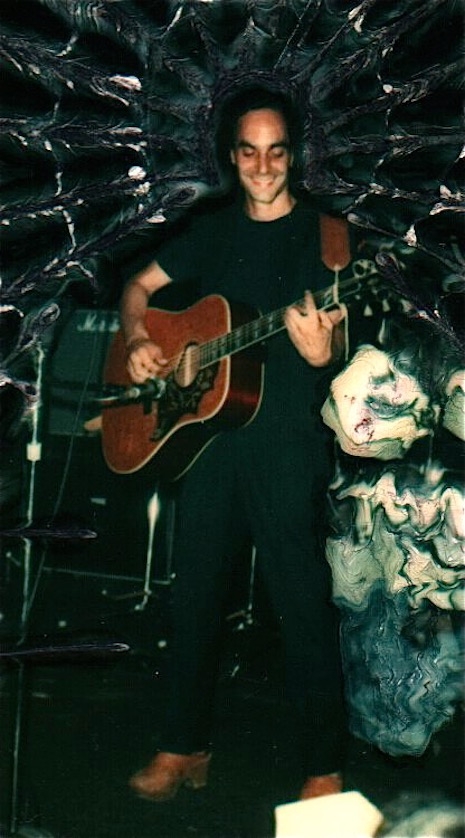

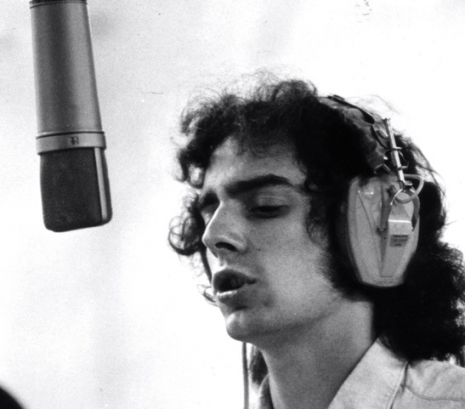

In late 1970, with dreams of making it in the music business, a 20-year-old Richard Goldman moved from his hometown of New Rochelle, New York to Los Angeles. “I wanted to be Jimmy Webb,” Richard told me recently (other inspirations include witty songsmith, Harry Nilsson; alt-country pioneer, Gram Parsons; and pop titans, the Beatles). His goal was to be a behind the scenes figure, thinking he would have a longer career as songwriter, rather than as a performer, as they tended to have shorter lifespans. But he wasn’t averse to playing his songs in public.

Richard became a fixture of the weekly open mic night at the Troubadour, then the hottest venue for singer-songwriters. After one such a set at the club, he was approached by an impressed member of the audience, Sam Weatherly, who became Richard’s manager and producer. Weatherly paid for demo sessions, which enabled Richard to record studio-quality versions of the songs he had been writing. For a session that took place at Sunset Sound, Weatherly brought in a musician by the name of George Clinton to play piano on a few tracks. Yep, the George Clinton.

Weatherly, who was older, “wasn’t just my manager,” Richard says today. “He was like a parent.” Richard would head over to Weatherly’s house often to have dinner, watch football, or play the board game Risk. Weatherly and his wife were like Richard’s west coast family.

In 1975, Richard recorded at the famed Sound City Studios. He’d actually recorded there a couple of years prior, and was invited back by one of the owners, Joe Gottfried. The engineer for the sessions, Fred Ampel, had taken on the managerial role in Richard’s career. By this time, Weatherly and Richard had drifted apart, though the circumstances are now unclear. Richard was thrilled to be recording again at Sunset Sound. “You knew you were in a very cool place.” Fleetwood Mac were right across the hall, and Lindsay Buckingham caught a playback of one of Richard’s songs, “Sinatra’s Car.” Buckingham expressed his admiration for the tune, noting that the bridge sounded Beatlesesque. He even lent a hand, overdubbing a bit of bass for a particularly tricky section of the track. “It was a thrill to watch,” remembers Richard. “He was ripped on pot but absolutely flawless on bass.”

Continues after the jump…