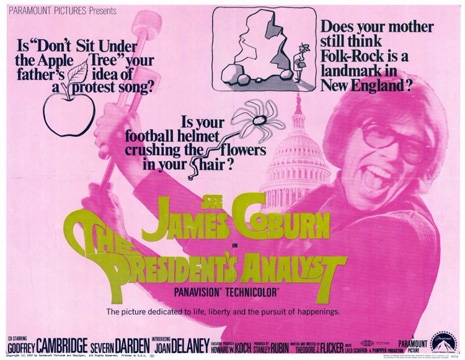

Twelve years ago I found myself at Cinefile Video in West Los Angeles when I happened to notice a movie poster on the wall for the 1967 film, The President’s Analyst. The duotone pink and green poster depicted James Coburn wearing a `60s mod wig and sunglasses holding two gong mallets in his hand with the tagline, “Is your football helmet crushing the flowers in your hair?” What the hell kind of movie is this? I had recently developed a fascination with James Coburn after discovering the sixties spy-spoof films Our Man Flint, and the sequel, In Like Flint. Perhaps it was due to exposure to late `90s pop culture references like the Beastie Boys album Hello Nasty or the movie Austin Powers (both of which named dropped the character Derek Flint) that Coburn had been embedded into my subconscious at that time.

I went home that night and watched The President’s Analyst. It was absolutely fantastic in the way it ridiculed virtually every important `60s institution—establishment and anti-establishment alike. But unlike most 1960s-era political satires and comedies, it was surprisingly fresh, relevant, and still laugh-out-loud funny in the present age. A man I had never heard of named Theodore J. Flicker was credited as the film’s writer and director. After repeated viewings I began to wonder: who is Theodore J. Flicker? How come nobody’s ever heard of him? How is it possible for someone to make a film this good and then vanish completely from sight? The lack of information available on the internet only fueled my interest, but I eventually learned that Mr. Flicker had been blacklisted from Hollywood. But why, how could that happen? I would end up going to great lengths to answer these questions, including a trip to Santa Fe, New Mexico to find Flicker, who spent the last twenty years of his life as a sculptor.

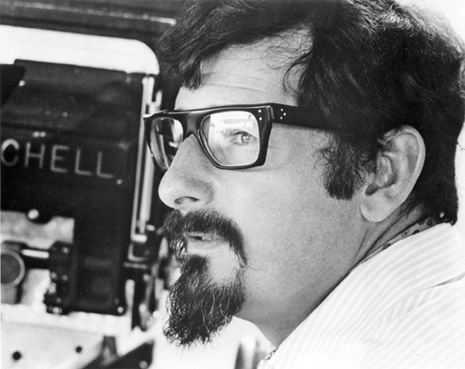

Ted Flicker in Santa Fe, Sept 2013. Photo by Doug Jones

After failing to open a theater of his own in New York City, Theodore J. Flicker headed to Chicago in 1954 to check out the improvisational Compass Theatre by recommendation of his college friend Severn Darden. According to Flicker, the Compass was in terrible shape when he entered: the players were unprofessional, wore street clothes, had a lack of respect amongst their fellow performers, and were basically “all over the place.” However, Flicker saw potential in the company and in 1957 he launched his own wing of The Compass Players at the Crystal Palace in St. Louis. Mike Nichols and Elaine May arrived in St. Louis, and Flicker auditioned Del Close who had come highly recommended by Darden despite the fact that he had no previous improv experience. Ted hired Del on the spot after seeing him perform a fire-breathing act from the work of Flaminio Scala. They all felt that the “meandering” Chicago style of improv did not sustain the audience’s attention for an entire show. Realizing that new techniques were needed if improvisation were to transform from an acting exercise into an art form, Flicker began developing a new technique which he referred to as “louder, faster, funnier”… the audiences responded. His goal was to re-create the Chicago Compass without any of the people involved and without the experience of Viola Spolin’s teachings, Flicker wanted to invent his own way. Every morning after a show, he would sit down with Elaine May and examine what went wrong the previous night and then determine how it could be corrected. Through these sessions “The Rules” for publicly-performed improv were formulated, including the importance of the Who? Where? and What? of each scene needing to be expressed, avoiding transaction scenes, arguments, and conflict as they usually lead to dead ends, and playing at the top of one’s intelligence. “We came up with a teachable formula for performing improvisation in public in two weeks,” Flicker said. These new rules differed greatly from the rules of Viola Spolin, who wasn’t a performer and explored improv only as an acting exercise. This was a new era of improvisation.

Following the collapse of The Compass Players, Paul Sills launched the successor troupe “The Second City” in 1959. Nichols and May went on to become a smash hit on Broadway. Del Close moved back to Chicago and spent the rest of his life developing, refining, and experimenting with Ted’s rules. Del became an improvisational guru for three decades with a student roster that included Dan Aykroyd, John and James Belushi, John Candy, Bill Murray, Chris Farley, Andy Dick, Harold Ramis, Mike Myers, Bob Odenkirk, Stephen Colbert, Amy Sedaris, Andy Richter, Tina Fey, and all three founding members of the Upright Citizens Brigade (Matt Walsh, Matt Besser, and Amy Poehler.) Unquestionably some of the biggest and most influential names in the comedy world, and it all circles back to Flicker. “I never could have done it without the sheer force of Ted’s will and discipline,” Close said.

But what was next for Theodore J. Flicker? In the sixties he wed Barbara Joyce Perkins, television actress and star of dozens if not hundreds of commercials, and the two set their sights on Hollywood. Theodore’s first feature film The Troublemaker, which he co-wrote with Buck Henry, described as an “improvised adventure” and was a moderate success, and the next thing he knew the phone started ringing. He was offered to write a feature film to launch the careers of Sonny and Cher; however, when the project fell through Flicker instead penned a screenplay for Elvis Presley, the 1966 “racecar musical comedy” Spinout.

It was Paramount Pictures that gave Flicker a chance to write and direct a major motion picture studio film in 1967, the first movie Robert Evans greenlit as a studio executive. The President’s Analyst was a fantastic, on-target satire. James Coburn plays Dr. Sidney Schaefer, who is awarded the job of the President’s top secret psychoanalyst. When Dr. Schaefer’s paranoia sinks in and he realizes he “knows too much,” he decides to run away and the film becomes a fast-paced action adventure romp involving spies, assassins, the FBI, CIA, a suburban family station wagon, flower power hippies, and even a British pop group. An unusual sci-fi plot twist reveals the movie’s most surprising villain: The Telephone Company (referred to in the film as “TPC”).

Problems began when the FBI got ahold of the screenplay. Robert Evans claims he was visited by FBI Special Agents who didn’t appreciate their unflattering and incompetent portrayal in the film. When Evans denied their request to cease production, they began conducting surveillance on the film’s set. Evans refused their demands, but increasing pressure led to extensive overdubs during the film’s post-production phase: the FBI became the FBR, and the CIA became the CEA. Even the Telephone Company got wind of their negative portrayal in the film, and Evans believed that his telephone had begun to be monitored by either the Bureau or the phone company. Evans’ paranoia would ironically mirror that of James Coburn’s character in the film’s storyline.

The President’s Analyst hit theaters on December 21st, 1967, the same day as Mike Nichols’ The Graduate. Both films were instant hits and received critical and box office praise. Roger Ebert called The President’s Analyst one of the “funniest movies of the year.” However, two weeks later Flicker received an unsettling phone call from his agent who told him, “You’ll never work in this town again.” Apparently FBI head J. Edgar Hoover had seen the film and was outraged by 4’7” actor Walter Burke whose character name Lux (like Hoover, a popular brand of vacuum cleaner) as the head of the “FBR” was blatantly poking fun at him. J. Edgar called the White House who called Charles Bluhdorn at Paramount, who called Flicker’s agent to inform him they were pulling the movie from theaters immediately. “What the hell are you trying to do to me?” Bluhdorn said on a phone, “But we have a hit!” “What the hell do I care about your hit, I have 27 companies that do business in Washington?” A millionaire at age 30, Charlie Bluhdorn didn’t just own Paramount; he owned Gulf and Western, Madison Square Garden, and Simon & Schuster publishing. As Flicker delicately put it, “The shit hit the fan.” Overnight he was officially no longer part of Hollywood’s A-list. He and Barbara had to foreclose their home and his agent stopped returning his phone calls.

More on the life and times of Ted Flicker after the jump…