It is extremely difficult to republish a long out of print book. I know this because I have actually done it myself. First off, a pre-computer era book was typeset by hand, so the text will not often exist as a digital file. This presents the option of either rekeying in an entire book, or else scanning in each page individually. Doing it with some sort of image-to-text OCR program only makes for introducing new problems. It’s a time consuming process and a pain in the ass. Anything beyond text such as illustrations and photographs need to be handled differently.

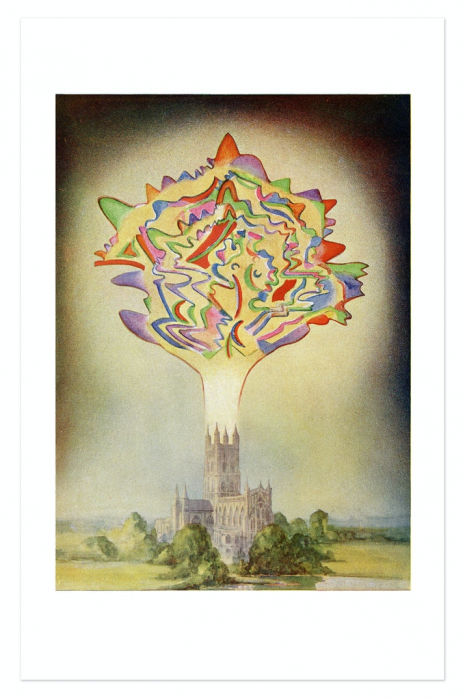

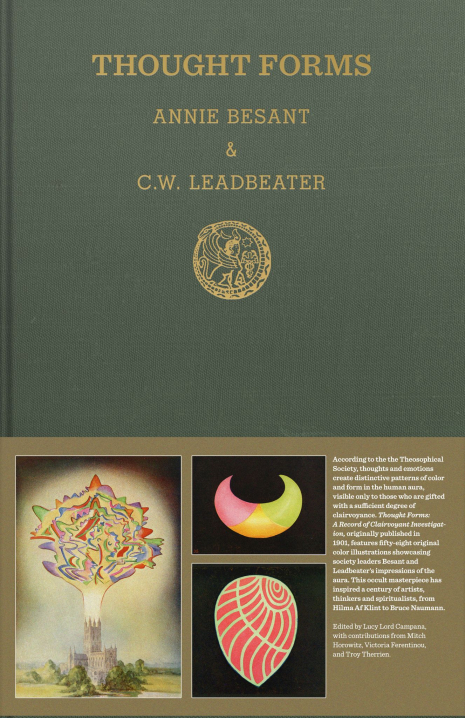

Which is why this exquisite recreation of the 1901 Theosophist publication Thought Forms: A Record of Clairvoyant Investigation is so noteworthy. This isn’t an example of merely putting out a new version of a book, but the complete recreation of the original object as it was 116 years ago. It’s beautiful. Although long out of print in its original form, and nearly forgotten, Thought Forms can be seen as an influential but overlooked link between esoteric thought and modern art. Certainly there’s been no other book like it, before or since.

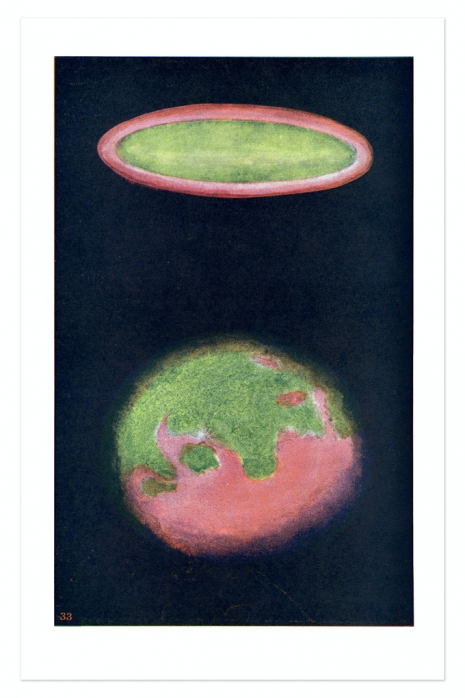

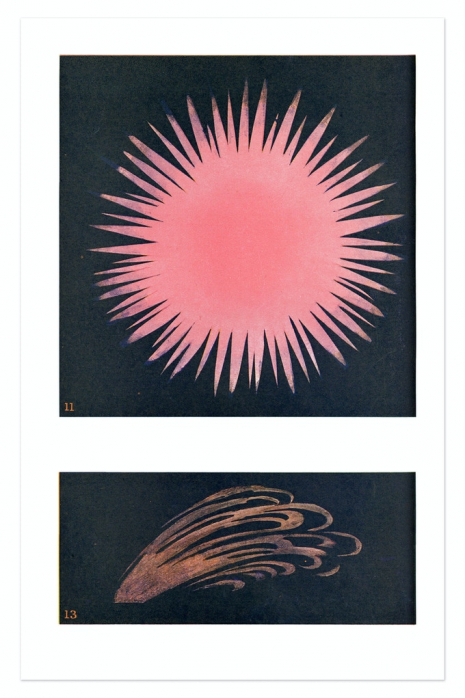

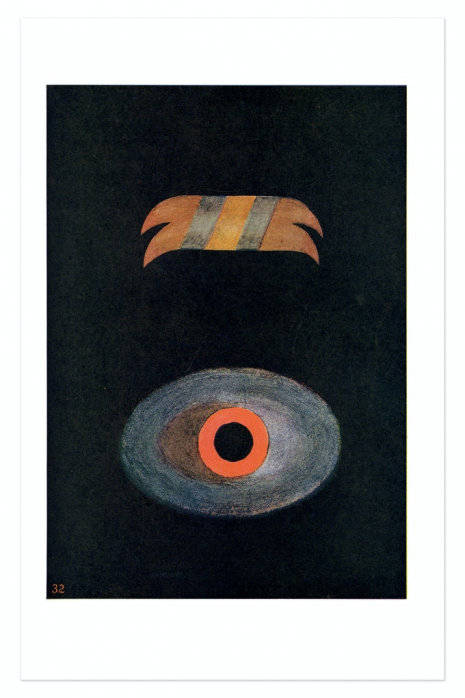

The volume explored the ideas of the occult society as they related to art, specifically the notion that certain people—clairvoyants—could sense and see energy and emotions in the auras of human beings. A person of high character would have a “clear” aura, whereas a selfish, insensitive brute’s aura would be cloudy and so on. Theosophist leaders Annie Besant and C. W. Leadbeater dictated their clairvoyant “thought-forms” to a group of followers who created the beautiful and unusual 58 illustrations seen in the book.

Published by Sacred Bones Books, an imprint associated with the Sacred Bones record label, the principals involved originally set the project up on Kickstarter which was a resounding success:

We learned of Thought Forms a few years ago and it completely took us by surprise. This one book totally challenged the classic art history narrative that had been taught to in school. Not like we fundamentally believed that story, abstraction is found in all cultures—not just in western 20th century painting, but the genesis story of a few male painters “inventing” abstraction does have its truths.

In this narrative of Modernism, Wassily Kandinsky is widely viewed as one of the most important founders of abstraction, and his manifesto “On the Spiritual in Art” is mandatory reading in art school.

What was never mentioned to us in school however, was that Kandinsky was a member of the Theosophical Society, and had acquired a copy of their book Thought Forms a few years before he abandoned conventional ways of painting. Learning that Kandinsky didn’t just come upon these ideas on his own as previously thought, totally changed our understanding of his work. It’s worth mentioning that Piet Mondrian was also deeply influenced by Theosophy and later on, Jackson Pollock was as well.

Last year the Guggenheim held the first US retrospective of Hilma af Klint’s paintings. She was a member of the Theosophical Society and was undoubtedly influenced by the spiritualistic currents of the time. Theosophy was the first occult group to open its doors to women, and it deeply questioned gender roles, many of these ideas are also in Af Klint’s paintings. This show was one of the first times the all-male origin story of abstraction was challenged within the ivory tower. Af Klint, made these paintings before Kandinsky, and she was a woman. Thought Forms came out before Af Klint began her abstract paintings and it is certain that she must have come across this book.

We’re republishing this beautiful, overlooked book, so that it may be widely accessible and no longer omitted from the past. Thought Forms offers a reminder that the history of modernist abstraction and women’s contribution to it is still being written.

Theosophy’s motto seems as appropriate today as it did in 1880, “there is no religion higher than truth.”

The new publication of Thought Forms: A Record of Clairvoyant Investigation was edited by Lucy Lord Campana, with introductory essays from renowned spiritualism expert Mitch Horowitz, art historian Dr. Victoria Ferentinou of the University of Ioannina and Troy Conrad Therrien of the Guggenheim Museum and Columbia University. A few of the book’s illustrations follow.