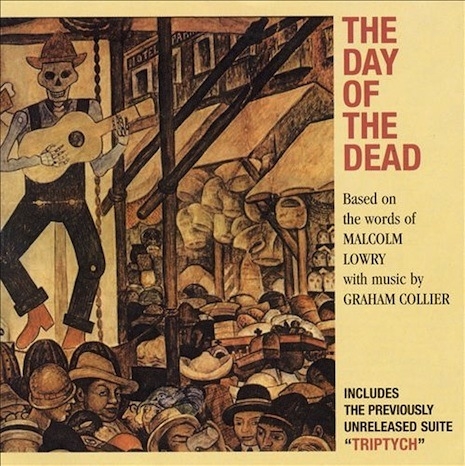

The loss of ignorance makes existence worthwhile. Two days ago I’d only vaguely heard of the late English composer and jazz musician Graham Collier (1937-2011) and would probably have never hooked up with his work if not for a tweeted image of his 1977 album The Day of the Dead that set me off on an Internet voyage of discovery.

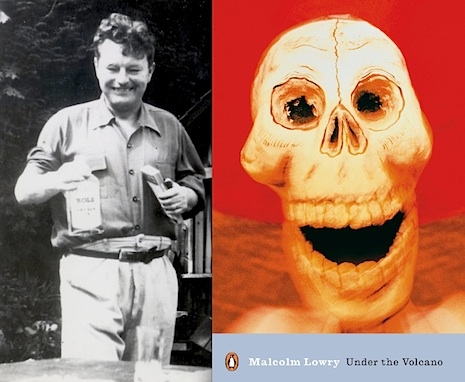

Collier was a musician, composer and teacher of considerable note—which only underlines my paltry knowledge—and wrote a significant body of work before his untimely death. But my attention was drawn to this photo by the name of the author on the cover of the album: Malcolm Lowry—one of the great misunderstood and underappreciated authors of the 20th century, whose books demand to be read and kept permanently in print—currently only one of his books is available, not surprisingly it’s his classic novel Under the Volcano.

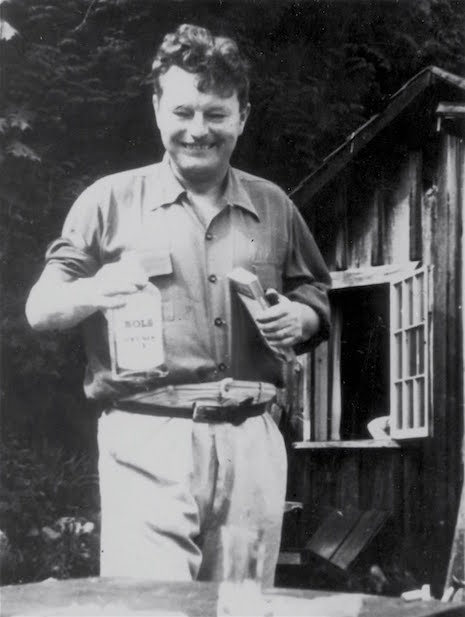

Little ole drink anything me, Malcolm Lowry and his classic book ‘Under the Volcano.’

Lowry’s Under the Volcano is the Faustian tale of Geoffrey’s Firmin, a British consul to Mexico, and his descent into a personal hell. This book inspired Collier to write The Day of the Dead, which was then described as his most “sprawling and ambitious” work as a composer.

Too often there is an awkwardness born out of improvised jazz and spoken word (listen to Jack Kerouac’s recordings) which can ruin good music and good words, but here Collier managed to wed Lowry’s words (culled from Under the Volcano and spoken by John Carbery) with his storm-tossed, intense music. It’s a revelation and has been deservedly hailed as his masterpiece. As critic Thom Jurek wrote of the album:

Collier’s vision here is focused, intense, and spiritually charged by Lowry’s work. This is not some jazz with text, where a written text becomes the thematic cause of a group of instrumentalists, but more a series of passages that offered great textural and spiritual depth and dimension by this obviously on fire group of musicians.

This is vanguard music, but it is far from “free jazz.” The gorgeous chromatic range is almost overwhelming as these players entwine around one another, and the text, further extending the entire notion of collaboration between literature and jazz.

The totality of this set makes for Collier’s most ambitious work yet, but also his most realized statement on record for a group of this size. This is the text for British and European big bands to follow.

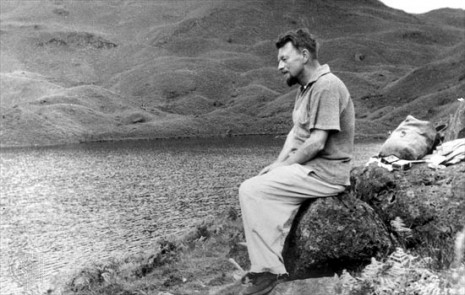

Graham Collier creating ‘the text for British and European big bands to follow.’

Collier had an understandable obsession with Lowry, as the writer mined a solitary path against insurmountable odds. In fact it was incredible that Lowry ever managed to write anything as his fondness for alcohol often had the better of him—here, was a man who would literally drink anything, including aftershave and hair tonic.

But Lowry for all his demons was a man who understood and loved life—he thrived in the joy and complexity of existence, writing everything down in his notebooks before it was all too quickly gone.

Listen to Graham Collier’s ‘The Day of the Dead,’ after the jump….