The artist and mystic Hilma af Klint (1862-1944) never described the 193 paintings she produced between 1906-15 as “Abstract art.” Instead, af Klint thought of these paintings as diagrammatic illustrations inspired by conversations she (and her friends) conducted with the spirit world from the late 1890s on.

That af Klint did not call her work “Abstract art” is enough for some art historians to (foolishly) discount her art as the work of the first Abstract artist. In fact af Klint was painting her Abstract pictures long before Wassily Kandinsky made his progression from landscapes to abstraction sometime around 1910, or Robert Delaunay dropped Neo-Impressionism for Orphism and then moseyed along into Abstract art just a year or two later. But these men were members of voluble artistic groups and Kandinsky was a lawyer who knew the importance of self-promotion. Unlike af Klint who worked alone, in seclusion, and stipulated that her artwork was not to be exhibited until twenty years after her death. Af Klint died in 1944. In fact, it took forty-two years for her work to be seen by the public as part of an exhibition called The Spiritual in Art in Los Angeles, 1986.

And there’s the issue. The word “spiritual.” In a secular world where anything with a whiff of bells and candles is considered irrelevant, contemptible, and generally unimportant, it has been difficult for af Klint to be seen as anything other than an outsider artist or a footnote to the boys who have taken all the credit. Of course, a large part of the blame for this must rest with af Klint herself and her own prohibition on exhibiting her work. It’s very unfortunate, for this self-imposed ban meant that although af Klint may have been (I’ll say it again) the very first Abstract artist, her failure to share her work or exhibit it widely meant she had no or very limited influence through her artistic endeavors.

But now that af Klint has been rediscovered, it’s probably the right time to rip up the old art history narrative about Kandinsky and Delaunay and all the other boys and start all over again with af Klint at the top of that Abstract tree.

Hilma af Klint was born in Sweden in 1862 into a naval family. Her father was an admiral with a great interest in mathematics, who could play a damn fine tune on the violin. Her family were Protestant Christians but took considerable interest in the rapid advances made by science into the world—from medicine and x-rays to the theory of evolution. Unlike today, religious belief and scientific investigation were not mutually exclusive. In the same way, there was (at the time) a scientific interest in the spiritual.

Af Klint was passionate about mathematics, botany, and art. Some of her earliest paintings were detailed examinations of plants. Her father had little understanding of his daughter’s passion for art and would ruefully shake his head when she enthused about painting. Af Klint studied portraiture and landscape at the Academy of Fine Arts in Stockholm 1882-87, graduating with honors. Her paintings are exceedingly good and technically very fine but not extraordinary or even offering much of a hint of what was to come.

The turning point for this great change roughly stemmed from the death of her younger sister. After her sister’s death in 1880, af Klint joined a group of women who shared an interest in the spiritual, in particular, the occult theories and Theosophical ideas of Madame Blavatsky who promoted a unity of the scientific and the spiritual. These women became known as “The Five.” They held séances together with af Klint often acting as the medium. The group made contact with spirit entities which they called the “High Masters.” Under their guidance, these women started producing works created by automatic writing and automatic painting—this was almost four decades before the Surrealists laid claim to inventing such techniques.

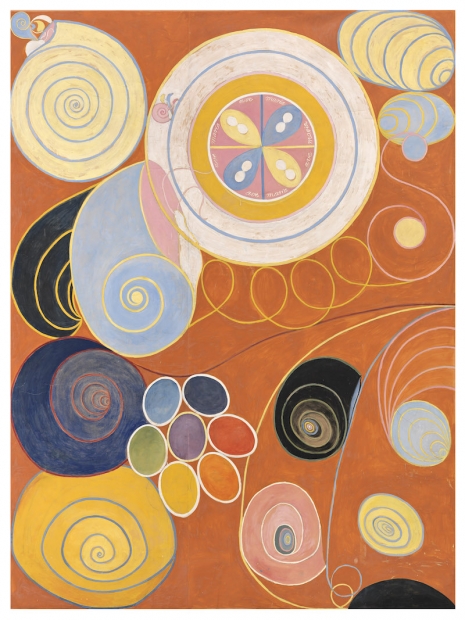

It was through her contact with these High Masters that af Klint began her series of Abstract paintings in 1906. These pictures, she claimed, were intended to represent “the path towards the reconciliation of spirituality with the material world, along with other dualities: faith and science, men and women, good and evil.”

Af Klint detailed her conversations with these spirits including one with a spirit called Gregor who told her:

All the knowledge that is not of the senses, not of the intellect, not of the heart but is the property that exclusively belongs to the deepest aspect of your being […] the knowledge of your spirit.

In 1906, af Klint began painting the images these spirits instructed her to set down. Her first was the painting Ur-Chaos which was created under the direction of the High Master Amaliel, as af Klint wrote in her notebooks:

Amaliel sign a draft, then let H paint. The idea is to produce a nucleus from which the evolution is based in rain and storm, lightning and storms. Then come leaden clouds above.

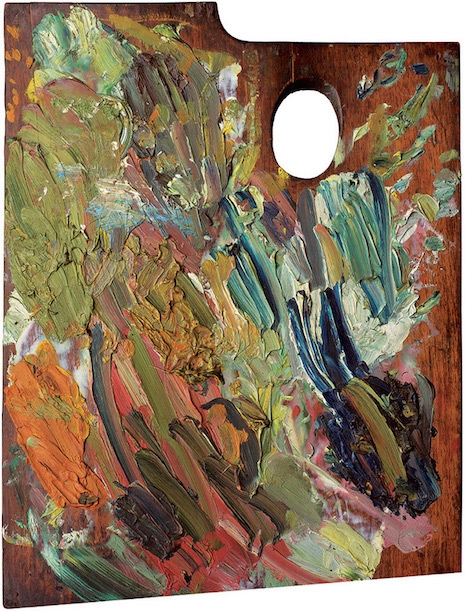

Between 1906 and 1915, af Klint produced a total of 193 paintings and an outpouring of thousands of words describing her conversations with the High Masters and the meaning of her paintings. Her work depicted the symmetrical duality of existence like male/female, material/spiritual, and good/evil. Blue represented the feminine. Yellow the masculine. Pink signified physical love. Red denoted spiritual love. Green represented harmony. Spirals signified evolution. Marks that looked like a “U” stood for the spiritual world. While waves or a “W” the material world. Circles or discs meant unity. Af Klint believed she was creating a new visual language, a new way of painting, that brought the spiritual and scientific together.

These paintings were often over ten feet in height. Af Klint stood around five feet. She painted her pictures on the floor—the occasional footprint can be seen smudged on the canvas. Af Klint worked like someone possessed. She believed her work was intended to establish a “Temple.” What this temple was or what it signified she was never exactly quite sure. All af Klint knew was that she was being guided by spirits:

The pictures were painted directly through me, without any preliminary drawings, and with great force. I had no idea what the paintings were supposed to depict; nevertheless, I worked swiftly and surely, without changing a single brush stroke.

All through this, af Klint continued her own rigorous investigation into new scientific and esoteric ideas. This brought her to the work of Rudolf Steiner who was similarly following a path towards creating a synthesis between the scientific and the spiritual. When af Klint showed her paintings to the great esoteric, Steiner was shocked and told her these paintings must not be seen for fifty years as no one would understand them.

Steiner’s response devastated af Klint and she stopped painting for four years. Af Klint spent her time tending to her blind, dying mother. She then returned to painting but kept herself and more importantly her work removed from the world. After her death in 1944, the rented barn in which she kept her studio was to be burnt by the landlord farmer. A relative quickly decanted all of af Klint’s paintings and notebooks into wooden crates and stored them in a tin-roofed attic for the next thirty years.

In 1970, af Klint’s paintings were offered to the Moderna Museet (Museum of Modern Art) in Stockholm which was surprisingly (some might say foolishly) knocked back. Thankfully, through the perseverance of her family and the art historian Åke Fant, af Klint’s work was eventually exhibited in the 1980s. In total, Hilma af Klint painted over 1,200 abstract paintings and wrote some 23,000 words, all of which are now owned and managed by the Hilma af Klint Foundation.

‘The Ten Largest #3’ (1907).

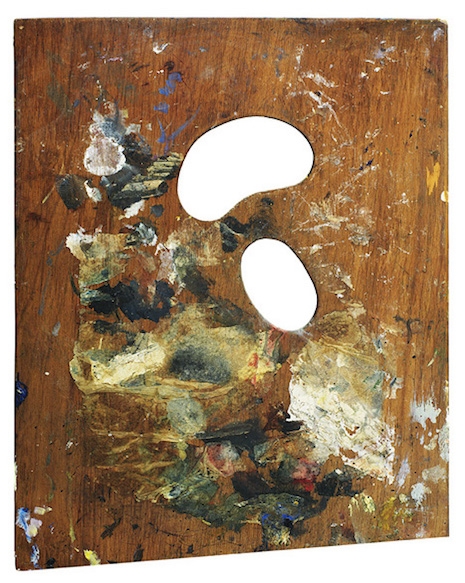

‘The Ten Largest #4’ (1907).

‘The Ten Largest #7.’ (1907).

More Abstract art from Hilma af Klint, after the jump…