If it’s ever been your dream to produce a feature film, the good news is it’s easier and cheaper than ever. In fact, I just did exactly that and I’d like to share some thoughts and experiences on the process with any first-time would-be filmmakers out there looking to get started. I’m talking about doing it on the cheap.

First, a bit of background: I’ve always wanted to make movies. When it came time to go to college I couldn’t afford to go to a fancy film school, so I studied Media Arts at the local university. The degree I received was, in practicality, fairly worthless, and my college experience, if anything, dissuaded my interest in film. The curriculum pushed students toward industrial videos and commercial work—and that held no interest for me at all. I got out of college and, instead of going to Hollywood to gofer coffee for actors and execs on movie sets, I opened a record store. Records are my other great love. And so I have worked in record stores ever since, for twenty years, with the idea still always in the back of my mind “one day I’m gonna make movies.” Until, finally, one day I realized that I wasn’t getting any younger and it was time to either shit or get off the pot.

There were two catalysts that ultimately resulted in me producing and directing my first feature (which I just completed this month). The first was the inspiration of a filmmaker in my hometown named Tommy Faircloth who had made a horror feature called Dollface in 2014 for under $10,000. Citizen Kane, Dollface was not, but it looked and felt enough like a “real movie” to get me really excited about what one could be capable of on an extreme micro-budget. The second catalyst was my friend David Axe, a war journalist and would-be screenwriter expressing some frustration over breaking through in Hollywood. My thought at the time was “if I’ve always wanted to make a movie, and you’re trying to get your words on the screen, and if our friend Tommy can make a movie for less than $10K, then what are we waiting for? Why don’t we just get our act together and make a movie?”

We entered into “our first feature” looking at it as a “learning exercise” and I think this is an important attitude to have. Your first movie is bound to have a lot of mistakes, but you can look at the overall project as a success if you learn from any mistakes made. It doesn’t necessarily have to be good... it just has to be.

Ultimately, we decided that we were going to make a movie to learn how to make a movie and the only unbreakable rule we set for ourselves was “no matter what, no matter how disappointed we might possibly be with the end result, we have to FINISH THE PROJECT.” In hindsight, that was the perfect gameplan. If you know that finishing is a foregone conclusion, then that frees you up to concentrate more on the details of getting to that finish line. Ultimately, I ended up with very few disappointments in our completed product outside of some intermittently imperfect framing, lighting, and audio. If you go into the project with this attitude then the only way to fail is to do nothing.

And so David and I moved forward, brainstorming the things we could afford to put into a movie as far as locations, actors, and effects go. You have to use locations you can access for free. You have to have a small cast—ours was probably too big.

We made an “Exploitation 101” laundry list, informed by the entire history of low-budget cinema, of items to include in our feature to make up for the fact that our film would have no name actors and would likely suffer from dodgy production value.

If you are looking to make your first no-budget feature, I highly recommend going the genre route… particularly horror. Horror fans are extremely forgiving of production quality and non-professional acting as long as the story is interesting. For us, it helped that my favorite movies are essentially horror and exploitation films ANYWAY, but it’s a hell of a lot easier to find an audience for a cheapo slasher flick than it is for a cheapo rom-com. Without going into great detail about our list, essentially we were looking at some form of sex, violence, or general strangeness at least every five script pages. If you don’t titillate your audience every five minutes, they are going to start to notice, say, how shitty your lighting is. I mean, they’re going to notice that anyway, but they are much more forgiving if they are constantly distracted from it.

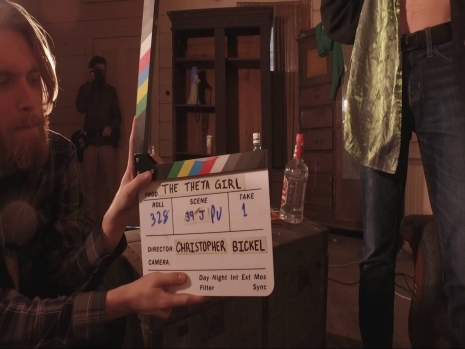

From that list, David wrote the script for our first feature, The Theta Girl, a psychedelic horror revenge story.

Our story contained all of the “Exploitation 101” elements we had laid out, but it also attempted to subvert some of those tropes. We also made sure it passed the Bechdel Test— because movies should do that anyway (though, to be fair, the horror genre as a whole tends to be better about this than most other genres).

One thing that was important to us, and I will offer this as a bit of advice to new filmmakers: make a film that can be categorized as a genre film, but DO NOT remake shit people have already seen. A $10,000 version of Friday the 13th is not only unnecessary, but it’s likely to be boring, and it certainly won’t win you any word-of-mouth unless you are able to go way-the-fuck-over-the-top with the kills. The best thing you can do as a new filmmaker, working under the duress of a microscopic budget, is to make a film that’s sort of like other things that people already enjoy, but also totally fucking different from everything else. Granted, this isn’t the easiest thing in the world, but no matter what your budget is, imagination is free (unless you’re paying a screenwriter—but if you can afford to do that, then why are you reading this?)

So what did we do next? What should you do next once you have an entertaining story ready to go? We brought in people to work and made the decision to pay everyone on our production. Not much, mind you… but enough to make it worthwhile for actors and crew to show up on set. Now you could (and a lot of people do) make a film with an all-volunteer cast and crew, but I am going to tell you from my first-timer experience that unpaid people will quit the first day that everything sucks… and you will have plenty of days where everything sucks. I’ll get more into this later, but making movies is really, really, really, really fucking hard.

I suggest paying a day rate to your cast and crew and have them sign a contract stating that they will be paid at the end of production for all days worked, but the contract becomes void if they quit before the end of production. This contract is assurance that the crew members will be paid, but also your insurance that the actors won’t bail on the project after you have 3/4 of the thing shot. Make meticulous records of days worked. Treat everyone fairly. Pay them as soon as you wrap shooting. We paid a flat $50 a day for every actor and crew person. This is admittedly jack-shit, but it was what we could afford and just enough to keep everyone motivated.

Having made that decision to pay or not to pay (PAY THEM!), you can then do a casting call and find some crew. Working on a mega-low budget means you will probably be hiring inexperienced crew who are looking to learn. Give them the opportunity to learn with you and allow them some room to fuck up with you.

Paying everyone meant that we were going to be spending a bit more than we had originally thought when the script was written. In hindsight, our script was rather (as one filmmaker friend delicately put it) “ambitious,” and probably a bite bigger than we had any right chewing.

Full disclosure here, it actually cost us $14,000 to make The Theta Girl, but had I known then what I know now, with better planning, we could have easily brought it in at $10K. Unfortunately, without ever having made a movie, there’s no real way to know how to plan your shooting days until you’ve actually done it. We ended up spending much of our budget paying multiple actors and crew members for multiple days that could have been more efficiently scheduled. My advice to new filmmakers on this front is: read as much as you can about pre-production. Plan for EVERYTHING. Think of every possible contingency. Storyboard everything. Create shotlists that you will stick to during production. Assume low-paid actors are going to be late a lot and have someone on your team whose job it is to pleasantly harass and wrangle them into being where they are supposed to be when you need them.

Knowing that money was likely to be extremely tight, we decided to do a crowd-funding campaign for our project. Now, in general, I’m not a huge fan of crowd-funding campaigns, but there is a way to do them “right” and, in retrospect, I think the crowd-funding campaign is a really smart idea beyond money generation. First of all, don’t be an entitled asshole with your campaign. No one owes you anything for “being cool” or making something that only you think is “awesome.” The best way to manage your campaign is to “pre-sell” your film or items related to your film. You can also “sell” roles and production credits. If people believe in your project, they will be more than happy to contribute. How will they believe in it? You must demonstrate that you are serious and capable, and that can take a bit of convincing. For us, having never made a movie before, the big looming question was “how do we demonstrate that we are capable of doing this?” It’s not like I had a showreel. I’d never made a movie before. Ever.

So what we did was this: We made a trailer for a fake movie in order to demonstrate that we could operate our gear and edit something together into a cohesive and entertaining form. This fake movie trailer also served the immeasurably benefitting purpose of allowing us to work with the actors we had just cast and the crew members we brought on board. It was also a good dry-run at learning how to direct and edit on a smaller scale before jumping totally into the deep end of a 90-minute feature head-first. It allowed us to make sure none of our hires were flakes or divas (they weren’t!). We decided to make a trailer for an imaginary movie INSTEAD of a direct trailer to The Theta Girl because we wanted to keep some element of mystery as to what our feature was going to be.

Continues after the jump…