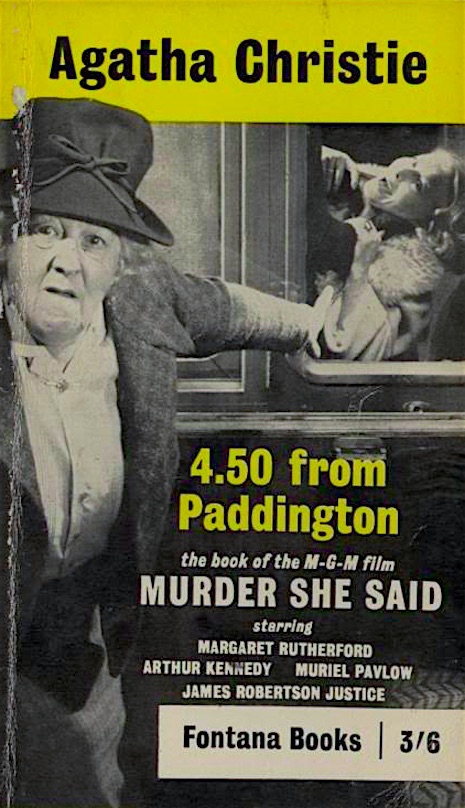

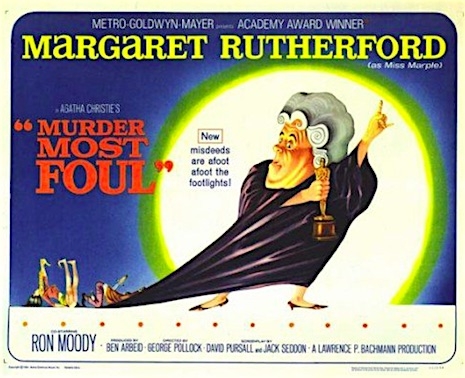

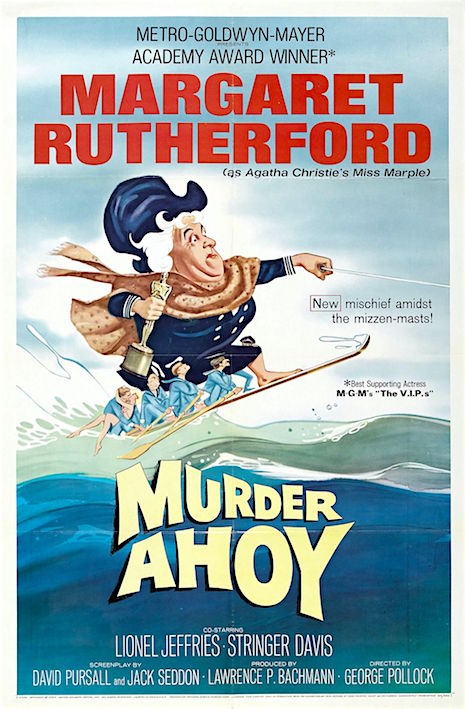

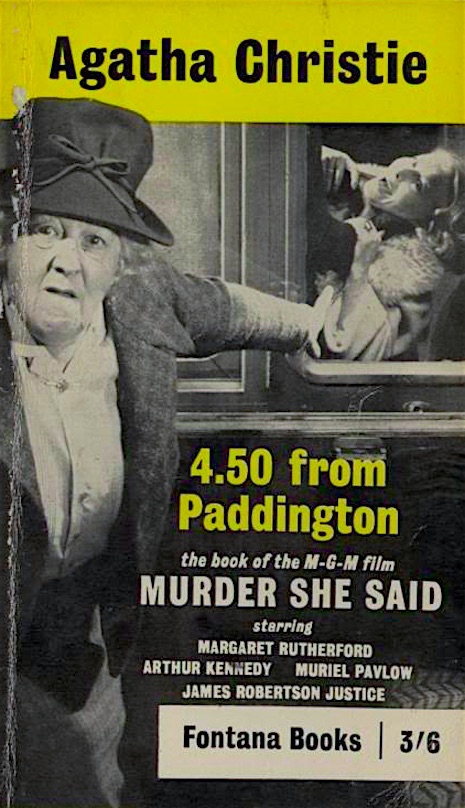

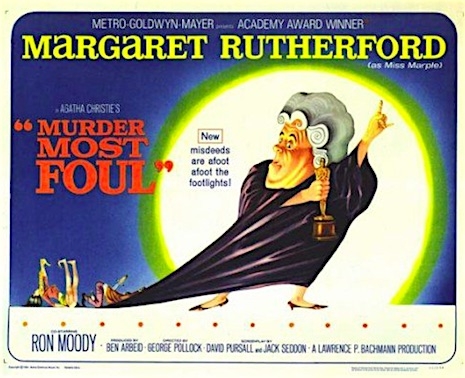

Sunday afternoon matinees on television first introduced me to the utter delight of watching Margaret Rutherford’s acting on screen. Her appearance as the much loved Miss Marple in a series of 1960s whodunnits loosely based on the novels by Agatha Christie left such an indelible impression that for all of those great actresses who have since played the inquisitive spinster from St. Mary Mead not one has eclipsed her unforgettable performance.

There was always something special about Margaret Rutherford. No matter what she did, she was always likeable. Over a thirty-year career on stage and screen she consistently delivered performances of quality and distinction, of grace and beauty, of comedy and excellence that made her sparkle in even the most second rate production.

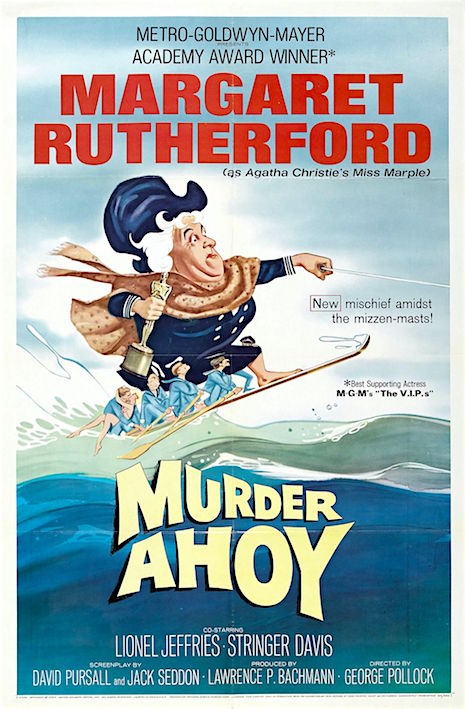

Nowadays she is best remembered for her scene-stealing turn as Madame Arcati in David Lean’s movie adaptation of Noel Coward’s Blithe Spirit in 1945. Or her fighting the battle of the sexes as headmistress of a girls school in The Happiest Days of Your Life from 1950. Or her 1963 Oscar-winning role as the Duchess of Brighton in the Richard Burton/Elizabeth Taylor movie The V.I.P.s.

As the actor Robert Morley once said, Margaret Rutherford was “everyone’s Maiden Aunt—a woman of enormous integrity who acted naturally…and was always frightfully funny.” Yet behind all this talent to amuse was a terrible secret worthy of a Miss Marple mystery—a story of madness, suicide and murder that haunted the great actress throughout her life.

To unlock this family secret we have to go back to the decade before Margaret Rutherford’s birth—to the marriage of her parents William Rutherford Benn and Florence Nicholson at All Saints Church, Wandsworth in December of 1882.

William was the son of the Reverend Julius Benn, an eminent social reformer and church figure and the grandfather of politician Tony Benn. Florence was of similar middle class stock but her parents were dead and one sister had committed suicide a few years before—which was an intimation of things to come.

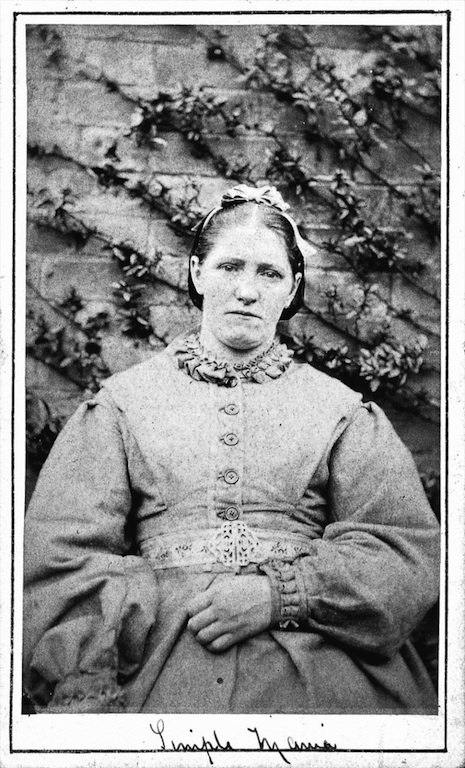

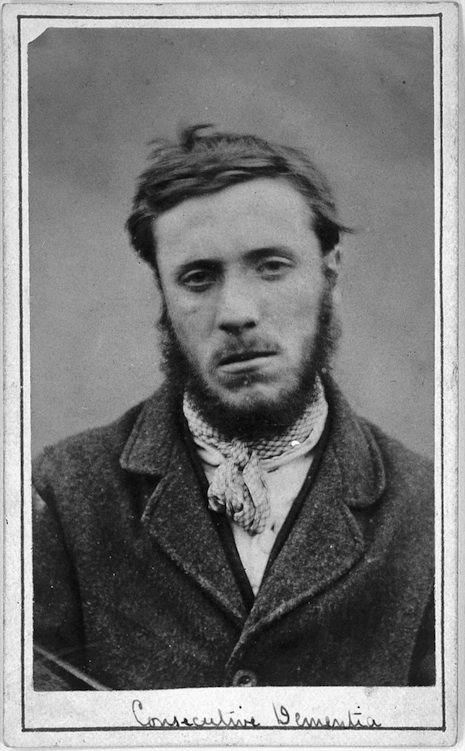

Not long after their honeymoon, William had a serious psychotic breakdown. It has been suggested this was caused by his failure to consummate the marriage. Exactly a month after their wedding, William was admitted to Bethnal House Lunatic Asylum, where he was described as suffering from:

...depression alternating with unusual excitement and irritability.

William was detained at the asylum for several weeks until his condition improved. On release, his parents decided it best that William should not return immediately to Florence but instead take “a rest cure in the country.” William’s father the Rev. Julius decided to take his son to the spa town of Matlock in Derbyshire.

On February 27th, 1883, the two men checked into their room at a boarding house run by a Mrs Marchant in Chesterfield Road. Father and son appeared “on the most affectionate of terms” and were “very attached to each other.” They were described as “abstemious” and were seen taking long walks to various local sites.

But on Sunday March 4th something terrible happened.

The first indications of there being wrong was the strange ghastly noises coming from their room. When neither men appeared for breakfast:

Mrs Marchant, accompanied by her husband, entered the Benns’ room to find William Benn, his night shirt covered in blood, pointing to his father, who lay on the bed quite dead.

William had killed his father with a single blow to the head with an earthenware chamber pot. William had then attempted suicide by cutting his own throat. He stood in the room making feral noises blood bubbling from the gash in his throat.

This self-inflicted was not fatal. William was arrested and treated at the local infirmary. A few days later he attempted suicide again this time by jumping out of a second story window. He suffered injuries to his back and cuts to his body but was not seriously hurt. He was recaptured and held at the hospital.

At the inquest, the jury unanimously decided William had “wilfully murdered” his father. He was committed to the mercy of the Derbyshire Assizes for sentencing. William’s condition deteriorated drastically. He was declared “insane” and admitted to Broadmoor hospital. All charges against him were dropped on grounds of insanity.

What caused this tragic psychotic episode is unknown. William was treated at Broadmoor for seven years, after which he was released into the care of his wife Florence.

In a bid to escape the association with his murderous past, William changed his name from Benn to Rutherford by deed poll. This time the marriage was consummated and Margaret Taylor Rutherford was born on May 11th, 1892.

William moved his family to India, where he worked as a merchant or “shipping clerk” and sometime journalist. Little is known of what happened during these years other than the suggestion (from Tony Benn) that William was deeply moved by the poverty he encountered and dedicated his time to helping those in direst need.

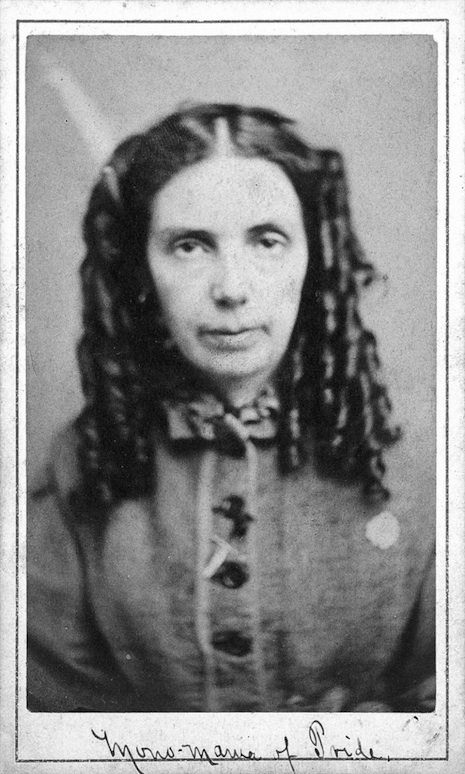

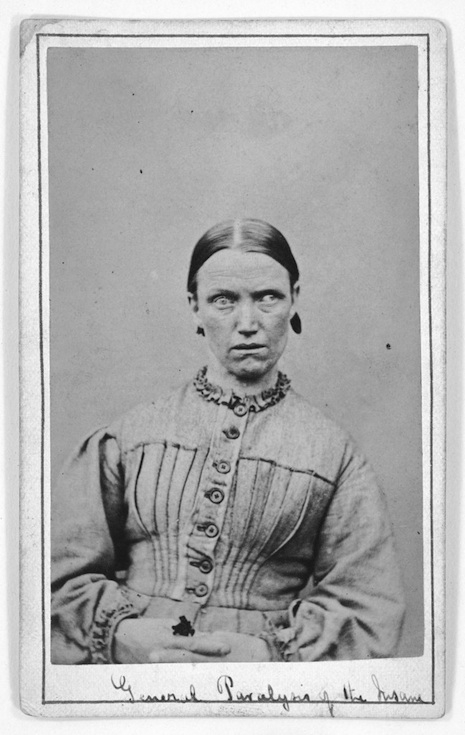

During their time together in India, Florence became pregnant. At some point during her pregnancy, Florence fell into a deep depression and exhibited signs of severe mental illness. Aware of his wife’s deteriorating condition, William made plans to move back to England. It came too late. Florence committed suicide. Her body was discovered one morning hanging from a tree in the garden.

In 1895, William and Margaret returned to England. He handed his daughter over to his wife’s remaining sister Bessie to raise. William then suffered a series of severe mental breakdowns that led to his incarceration at the Northumberland House Asylum, Finsbury Park, London in 1903.

Bessie took full charge of raising her niece. She told Margaret her parents were dead. All went well until one day a tramp approached Margaret as she played in the garden. This disheveled man told the young girl her father was very much alive and sent her his love. Margaret was terrified by the man and deeply troubled by what he had said.

She asked her aunt about her father. Bessie eventually told the truth. Margaret was devastated. She became depressed, withdrawn and non-communicative. Rutherford was terrified that she had inherited her parents’ insanity. She suffered the first of many mental breakdowns that she endured throughout her life, in later years going as far as undertaking electric shock therapy as a hopeful cure for her depression.

Margaret Rutherford never spoke publicly of her family’s history. In her autobiography, she made no reference to her father’s illness instead describing him as a:

...complicated romantic who changed his name to Rutherford as it was more aesthetic for a writer. My father died in tragic circumstances soon after my mother and so I became an orphan.

William had in fact been re-admitted to Broadmoor where he was incarcerated until his death in 1921. It is not known whether Margaret ever visited her father. However, he did write many letters to his daughter that caused her family considerable concern.

More after the jump…