Édouard Chimot was an artist, editor and writer whose career burned brightly through the 1920s but fizzled out during the 1930s and forties. His artwork was a last hurrah for the decadent world portrayed (and generally indulged in) by many French artists during the 1890s.

Born in Lille in 1880, Chimot studied at his local art college and at the École des Arts décoratifs in Nice. It’s fair to say, not much is known about Chimot during this period—though it has been posited he may have originally started out as an architect before switching career to becoming an artist. This may explain why he didn’t exhibit until he was in his early thirties in 1912.

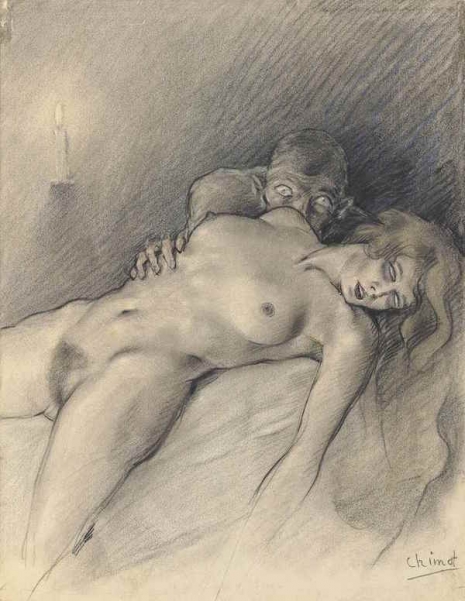

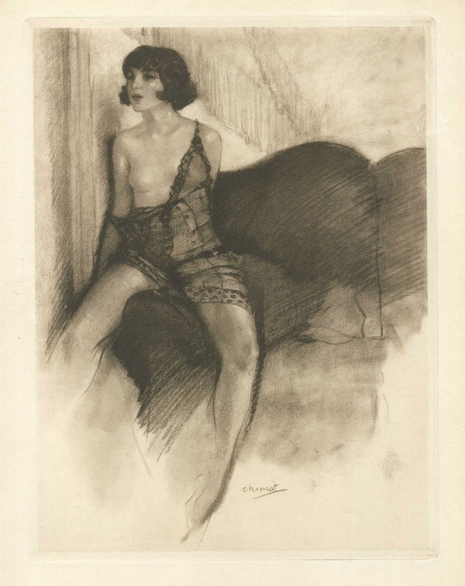

His first exhibition featured drawings, etchings and paintings of the “jeunes et jolies femmes”—the prostitutes and drug addicts who worked and lived near his studio in Montmartre. Chimot often paid these women to sit for him—as prostitutes were often cheaper to hire than models especially when paying by the night. He was heavily influenced by the Symbolist movement of the 1860s to 1890s—writers Charles Baudelaire, Stéphane Mallarmé, and Paul Verlaine; artists Félicien Rops and the Post-Impressionist Toulouse Lautrec. The success of his first show gained Chimot his a commission to illustrate René Baudu’s Les Après-midi de Montmartre—a depiction of seedy lowlife in Paris’s 18th arrondissement.

However, Chimot’s career was once again halted this time by a far more deadly and dangerous interlude—the First World War. Chimot served for almost five years in French army. One can only surmise what happened to him during this time. Yet, it may be possible to ascertain something of his grim experience from the comments of philosopher Ludwig Wittgenstein who once wrote that during war he never felt more alive than when in proximity to death. Wittgenstein’s bloody experience led him to some recklessness behavior—volunteering for several near fatal (if not downright suicidal) missions.

On leaving the trenches, this intense experience led Wittgenstein to a burst of creativity. Something similar undoubtedly happened to Chimot—who produced a large portfolio of drawings and etchings upon quitting the army. This portfolio formed the basis of illustrations published in books—including Les Après-midi de Montmartre.

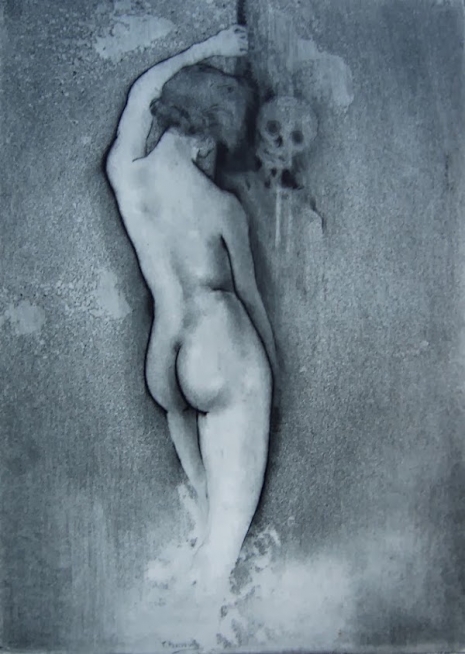

Most of these artworks were featured in limited edition books—which catered to the tastes of an exceedingly rich clientele. Chimot’s frenzied burst of activity produced his trademark monochromatic erotica of his favored “deadly and delicious passions”—prostitutes, drug addicts and lost young girls. His work tended to romanticize this shabby world of poverty, disease and addiction—but there are moments when his etchings captured some fleeting awareness at the depths of their despair. All that prostitution and skulls without thinking that men might have something to do with it.

Chimot’s career blossomed. He became an editor of Les Éditions d’Art Devambez—responsible for producing fine quality limited editions imprints of such infamous tales as Les Chansons de Bilitis, La Troisième Jeunesse de Madame Prune, Les Belles de Nuit and Mitsou. He also brought together a group of prominent writers and artists like Henri Barbusse, Collette, Pierre Brissaud and Tsuguharu Foujita.

However, his career came quickly unstuck by two very different forces—the major advances in art (Cubism, Fauvism, Dada, Surrealism and Abstraction) and most damagingly the Wall Street Crash which overnight killed off the demand for high-end exclusive erotica. Chimot carried on—but never to the same success. He moved to Spain where he produced artworks that now looked sadly dated, trite and often the kind of representations seen on sailor’s tattoos or low rent pulp magazines. The glory days of Chimot’s best work were over—the early 1920s when he produced some of the most memorable and haunting images for works of decadent literature.

More of Chimot’s decadent art, after the jump…