Turkey Day has passed us by, and it is officially the Christmas season. And, as the Pamplona of Black Friday reminded us, this means an onslaught of fevered consumerism, fetishizaton of commodities, conspicuous consumption, and all that other icky stuff that turns our red little stomachs stomachs. Exacerbating that nausea is the hallmark corniness of the holidays. “Peace on earth and goodwill towards men” can feel so cliched and forced when contrasted with the materialism of the spectacle. It’s easy to get a little contemptuous at Christmas.

It’s all reminiscent of George Orwell’s essay, “Why Socialists Don’t Believe in Fun.” A self-identified socialist, Orwell begins the piece with an anecdote on Lenin, who was, as the story goes, reading Dickens’ A Christmas Carol on his death bed. It’s said that communist revolutionary denounced the feel-good classic as full of “bourgeois sentimentality.” A fun guy, that one.

Orwell goes on to bemoan the kind of cynicism exhibited by Lenin and his ilk, noting that we dour anti-capitalists can’t seem to enjoy anything nostalgic or sentimental. I think anyone with much experience in radical circles has recognized the tendency. So in the interest of subverting our fuddy-duddy dispositions, allow me to show you one of my favorite Christmas music sub-genres: The Black Power Christmas Song.

Now, I’m not just talking about a Christmas song performed by a black artist, or even a Christmas song performed in a black genre. I am talking about a Christmas song that portrays Christmas itself as explicitly black. Let’s start with “The Be-Bop Santa Claus,” by Babs Gonzalez.

This 1957 update of T’was the Night Before Christmas starts out with the line, “T’was the black before Christmas.” Now Babs was a bebop pioneer and poet, and used to go by the name “Ricardo Gonzalez” in an attempt to get into hotels that discriminated against black people; that coy little line is an incredibly personal one. What follows is a perfect depiction of the Reaganite’s boogeyman, complete with suede shoes, Cadillacs, and Applejack; it’s fantastically subversive, unapologetic, and totally self-aware.

Of course, I can’t resist including the 1958 white hipster rip-off, “Beatnik’s Wish,” by Patsy Raye & the Beatniks.

It’s quite the (ahem) “homage.” Paging Norman Mailer…

If “The Be-Bop Santa Claus” alludes to urban poverty, James Brown’s “Santa Claus, Go Straight to the Ghetto” leaves nothing to the imagination.

“Say It Loud—I’m Black and I’m Proud” was released as a two-part single in August of 1968. This song was released a few months later on James’ full-length, A Soulful Christmas, which was the first LP to feature “Say it Loud.” Meaning James Brown, already a floating signifier for the Black Power Movement, released “Say it Loud—I’m Black and I’m Proud,” on a fucking Christmas album. Take that, Lenin!

It acknowledges black poverty as a pressing matter of social justice in a seemingly incongruously celebratory song. Second, the song applies radical Black Power politics to something as traditional as Christmas. (If I could add a third, I’d also say that this is just a sick jam, but I digress.)

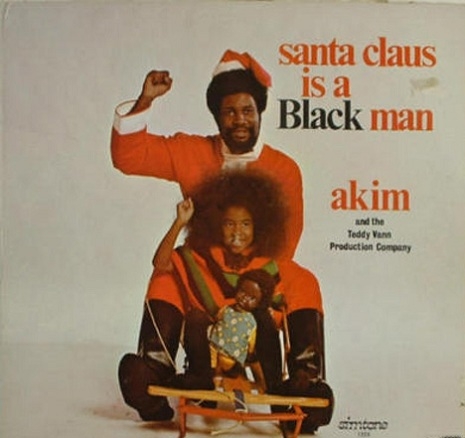

This one, however, is my absolute favorite.

Performed by Teddy Vann and his daughter, Akim, “Santa Claus is a Black Man” is arguably the most adorable product of Black Power. I mean look at that album cover! Look at her wee little Black Power fist! Listen to her sweet, spastic, bubbly little voice!

Not only can I not overemphasize the significance of radical children’s art being sung by an actual child (we so rarely give children the reigns, so to speak), “Santa Claus is a Black Man” is a brilliantly executed piece of kid-sized politics. You have a black child satirizing “I Saw Mommy Kissing Santa Claus,” which was originally sung by Jimmy Boyd, arguably the whitest damn child in the world. And the hook is, “and he’s handsome, like my Daddy, too,” an joyous assertion of “Black is Beautiful.”

Interestingly, towards the end, Akim says, “I want to wish everybody Happy Kwanzaa.” When Kwanzaa was first introduced in 1966, founder and activist Maulana Karenga promoted the holiday as a way to “give Blacks an alternative to the existing holiday, and give Blacks an opportunity to celebrate themselves and history, rather than simply imitate the practice of the dominant society.” Much to Karenga’s surprise, African Americans were rarely willing to give up the holiday of the oppressor, and eventually Karenga softened his position to allow Kwanzaa to be celebrated alongside Christmas, though not before “Santa Claus is a Black Man” was released in 1973. In the grand scheme of things, people don’t really want to be sectarian when it comes to Santa Claus.

Of course, none of this music succeeds in making Christmas cool. Even though these are great, subversive little songs, they’re also rife with the exact sort of schlocky sentimentality we’ve come to expect from Christmas music. And why shouldn’t they be? What’s so bad about sentimental and schlocky, anyway? Does Wal-Mart win if we enjoy a little syrupy holiday cheer? Will a few tender moments soften our anti-capitalist resolve? These songs are all navigating a very old tradition in order to reflect the radical ideas, the radical ideas we hope will become our new traditions. They use Christmas to represent the underrepresented and condemn racism and poverty, and they do it all with a little bit of mawkish sincerity and delight.

This Christmas, let’s resist our inner-Lenins, and let’s wallow in a little sentimentality. Hey, it was good enough for James Brown.