This is a guest post from Charles Hugh Smith. His newest book is Why Things Are Falling Apart and What We Can Do About It

Social recession is my term for the social and cultural consequences of a permanently recessionary economy such as that of Japan—and now, Europe and the U.S.

Forget Gross Domestic Product (GDP) as a measure of expansion (“growth”) or recession—what really matters is the social recession, which continues to deepen in America.

The term social recession has two distinct meanings: around 2000, the term was used to describe the erosion of social cohesion via the decline of institutions such as marriage and the rise of social problems such as teen pregnancy.

Many commentators pinned the responsibility for this erosion of social constraints and bonds on rampant individualism and overstimulated consumerism, while others pointed to urbanization, the commodification of child care, women entering the workforce en masse and similar trends. Poverty was explicitly rejected as a causal factor, hence the term “social recession.”

This notion of social recession was aptly described by Robert E. Lane, author of the 2001 book The Loss of Happiness in Market Democracies:

There is a kind of famine of warm interpersonal relations, of easy-to-reach neighbors, of encircling, inclusive memberships, and of solidary family life… For people lacking in social support of this kind, unemployment has more serious effects, illnesses are more deadly, disappointment with one’s children is harder to bear, bouts of depression last longer, and frustration and failed expectations of all kinds are more traumatic.

(For more on the subject, please see “The Social Recession” (The American Prospect.)

I use the term social recession to describe a very different phenomenon, the social and cultural consequences of permanently recessionary economies such as Japan, and now Europe and the U.S.

I have defined and used social recession in this way since 2010:

The Non-Financial Cost of Stagnation: “Social Recession” and Japan’s “Lost Generations” (August 9, 2010)

Here are the conditions that characterize social recession:

1. High expectations of endless rising prosperity have been instilled in generations of citizens as a birthright.

2. Part-time and unemployed people are marginalized, not just financially but socially.

3. Widening income/wealth disparity as those in the top 10% pull away from the shrinking middle class.

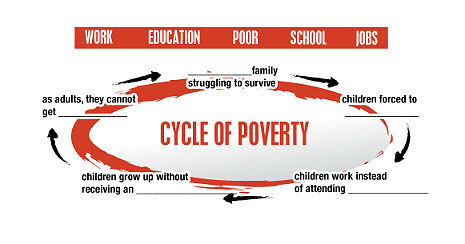

4. A systemic decline in social/economic mobility as it becomes increasingly difficult to move from dependence on the state (welfare) or parents to the middle class.

5. A widening disconnect between higher education and employment: a college/university degree no longer guarantees a stable, good-paying job.

6. A failure in the status quo institutions and mainstream media to recognize social recession as a reality.

7. A systemic failure of imagination within state and private-sector institutions on how to address social recession issues.

8. The abandonment of middle class aspirations by the generations ensnared by the social recession: young people no longer aspire to (or cannot afford) consumerist status symbols such as autos.

9. A generational abandonment of marriage, families and independent households as these are no longer affordable to those with part-time or unstable employment, i.e. the “end of work”.

10. A loss of hope in the young generations as a result of the above conditions.

I have described the “end to (paying) work” many times:

End of Work, End of Affluence (December 5, 2008)

End of Work, End of Affluence II: Cascading Job Losses (December 8, 2008)

End of Work, End of Affluence III: The Rise of Informal Businesses (December 10, 2008

Endgame 3: The End of (Paying) Work (January 21, 2009)

Demographics and the End of the Savior State (May 17, 2010)

What happens to the social fabric of an advanced-economy nation after a decade or more of economic stagnation?

For an answer, we can turn to Japan. The second-largest economy in the world has stagnated in just this fashion for almost twenty years, and the consequences for the “lost generations” which have come of age in the “lost decades” have been dire. In many ways, the social conventions of Japan are fraying or unraveling under the relentless pressure of an economy in seemingly permanent decline.

While the world sees Japan as the home of consumer technology juggernauts such as Sony and Toshiba and high-tech “bullet trains” (shinkansen), beneath the bright lights of Tokyo and the evident wealth generated by decades of hard work and the massive global export machine of “Japan, Inc,” lies a different reality: increasing poverty and decreasing opportunity for the nation’s youth.

The gap between extremes of income at the top and bottom of society—measured by the Gini coefficient—has been growing in Japan for years; to the surprise of many

outsiders, once-egalitarian Japan is becoming a nation of haves and have-nots.

The media in Japan have popularized the phrase “kakusa shakai,” literally meaning “gap society.” As the elite slice of society prospers and younger workers are increasingly marginalized, the media has focused on the shrinking middle class. For example, a bestselling book offers tips on how to get by on an annual income of less than three million yen ($30,770). Two million yen ($20,500) has become the de-facto poverty line for millions of Japanese, especially outside high-cost Tokyo.

More than one-third of the workforce is part-time as companies have shed the famed Japanese lifetime employment system, nudged along by government legislation which abolished restrictions on flexible hiring a few years ago. Temp agencies have expanded to fill the need for contract jobs, as permanent job opportunities have dwindled.

Many fear that as the generation of salaried Baby Boomers dies out, the country’s economic slide might accelerate. Japan’s share of the global economy has fallen below 10 percent from a peak of 18 percent in 1994. Were this decline to continue, income disparities would widen and threaten to pull this once-stable society apart.

Young Japanese, their expectations permanently downsized, are increasingly opting out of the rigid social systems on which Japan, Inc. was built.

The term “Freeter” is a hybrid word that originated in the late 1980s, just as the Japanese property and stock market bubbles reached their zenith. It combines the English “free” and the German “arbeiter,” or worker, and describes a lifestyle which is radically different from the buttoned-down rigidity of the permanent-employment economy: freedom to move between jobs.

This absence of loyalty to a company is totally alien to previous generations of driven Japanese “salarymen” who were expected to uncomplainingly turn in 70-hour work weeks at the same company for decades, all in exchange for lifetime employment.

Many young people have come to mistrust big corporations, having seen their fathers or uncles eased out of “lifetime” jobs in the relentless downsizing of the past twenty years. From the point of view of the younger generations, the loyalty their parents unstintingly offered to companies was wasted.

They have also come to see diminishing value in the grueling study and tortuous examinations required to compete for the elite jobs in academia, industry and government; with opportunities fading, long years of study are perceived as pointless.

In contrast, the “freeter” lifestyle is one of hopping between short-term jobs and devoting energy and time to foreign travel, hobbies or other interests.

As long ago as 2001, The Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare estimates that 50 percent of high school graduates and 30 percent of college graduates now quit their jobs within three years of leaving school.

The downside is permanently downsized income and prospects. Many of the four million “freeters” survive on part-time work and either live at home or in a tiny flat with no bath. A typical “freeter” wage is 1,000 yen ($10.25) an hour.

Japan’s slump has lasted so long, that a “New Lost Generation” is coming of age, joining Japan’s first “Lost Generation” which graduated into the bleak job market of the 1990s.

These trends have led to an ironic moniker for the Freeter lifestyle:

Dame-Ren (No Good People). The Dame-Ren get by on odd jobs, low-cost living and drastically diminished expectations.

The decline of permanent employment has led to the unraveling of social mores and conventions. Many young men now reject the macho work ethic and related values of their fathers. These “herbivores” also reject the traditional Samurai ideal of masculinity.

Derisively called “herbivores” or “grass-eaters,” these young men are uncompetitive and uncommitted to work, evidence of their deep disillusionment with Japan’s troubled economy.

A bestselling book titled The Herbivorous Ladylike Men Who Are Changing Japan by Megumi Ushikubo, president of Tokyo marketing firm Infinity, claims that about two-thirds of all Japanese men aged 20-34 are now partial or total grass-eaters. “People who grew up in the bubble era (of the 1980s) really feel like they were let down. They worked so hard and it all came to nothing,” says Ms Ushikubo. “So the men who came after them have changed.”

This has spawned a disconnect between genders so pervasive that

Japan is experiencing a “social recession” in marriage, births, and even sex, all of which are declining.

With a wealth and income divide widening along generational lines, many young Japanese are attaching themselves to their parents, the generation that accumulated home and savings during the boom years of the 1970’s and 1980’s. Surveys indicate that roughly two-thirds of freeters live at home.

Freeters “who have no children, no dreams, hope or job skills could become a major burden on society, as they contribute to the decline in the birthrate and in social insurance contributions,” Masahiro Yamada, a sociology professor wrote in a magazine essay titled, Parasite Singles Feed on Family System.

This trend of never leaving home has sparked an almost tragicomic counter-trend of Japanese parents who actively seek mates to marry off their “parasite single” offspring as the only way to get them out of the house.

An even more extreme social disorder is Hikikomori, or “acute social withdrawal,” a condition in which the young live-at-home person will virtually wall themselves off from the world by never leaving their room.

What we’re seeing in Japan is the confluence of three dynamics: definancialization, the demise of growth-positive demographics and the devolution of the consumerist model of endless “demand” and “growth.”

Japan is the leading-edge of the crumbling model of advanced neoliberal capitalism: that consumerist excess creates wealth, prosperity and happiness.

What consumerist excess actually creates is alienation, social atomization, narcissism,and a profound contradiction at the heart of the consumerist-dependent model of “growth”: the narcissism that powers consumerist lust and identity is at odds with the demands of the workplace that generates the income needed to consume.

Japan and the Exhaustion of Consumerism

The Hidden Cost of the “New Economy”: New-Type Depression

The Future of America Is Japan: Stagnation

The Future of America Is Japan: Runaway Deficits, Runaway Debts

The younger generation of workers raised in a consumerist “paradise” are facing an economic stagnation that reduces opportunities to earn the high income needed to fulfill the consumerist demands for status symbols. Given the hopelessness of earning enough to afford the consumerist lifestyle, they have abandoned traditional status symbols such as luxury autos and taken up fashion and media as expressions of consumerism.

But the narcissism bred by consumerism has nurtured a kind of emotional isolation and immaturity, what might be called permanent adolescence, which leaves many young people without the tools needed to handle criticism, collaboration and the pressures of the workplace.

Narcissism is the result of the consumerist society’s relentless focus on the essential project of consumerism, which is “the only self that is real is the self that is purchased and projected.”

Narcissism, Consumerism and the End of Growth (October 19, 2012)

In my analysis, this is the direct consequence of the supremacy of a consumerism that is dependent on financialization: an economy dependent on debt-fueled consumption to power its “endless growth” is one that will necessarily implode from its internal contradictions: debt and leverage eventually exceed the carrying capacity of the collateral and the national income, and the narcissism of consumerism leads to social recession, a crippling state of “suspended animation” adolescence and great personal frustration and unhappiness.

The ultimate contradiction in this debt-consumption version of capitalism is this: how can an economy have “endless expansion and growth” when pay and opportunities for secure, high-paying jobs are both relentlessly declining? It cannot. Financialization, consumerist narcissism and the end of growth are inextricably linked.

This leads to a dispiriting no exit:It’s as if there is a split in the road and no third way: some young people make it onto the traditional corporate or government career path, and everyone else is left in part-time suspended animation with few options for adult expression or development.

We need a third way that offers people work, resilience and authentic meaning. In my view, that cannot come from the Central State or the global corporate workplace: it can only come from a relocalized economy in revitalized communities.

For more on this topic:

Generational Wealth and Upward Mobility (October 24, 2012)

Priced Out of the Middle Class (June 28, 2012)

Do We Have What It Takes To Get From Here To There? Part 1: Japan (November 8, 2012)

Degrowth, Anti-Consumerism and Peak Consumption (May 9, 2013)

Tune In, Turn On, Opt Out (May 17, 2013)

Will Crushing Student Loans and Worthless College Degrees

Politicize the Millennial Generation? (May 31, 2013)

The Recession That Never Ended: 2008 -2013 (and Counting) (August 26, 2013)

This is a guest post from Charles Hugh Smith. His newest book is Why Things Are Falling Apart and What We Can Do About It