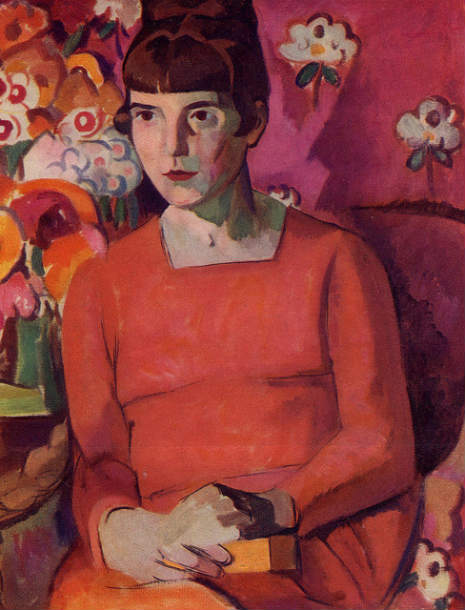

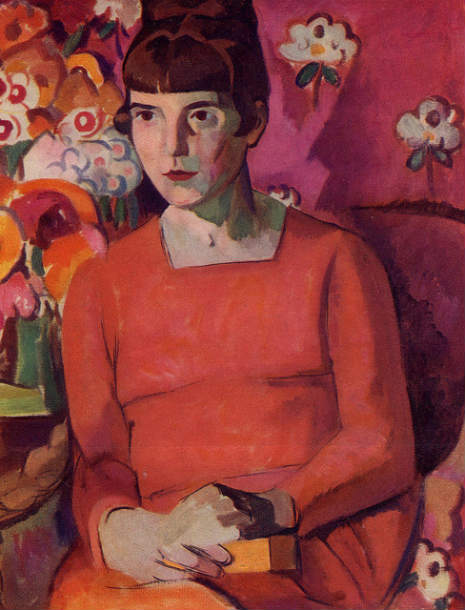

Virginia Woolf was never sure of Katherine Mansfield. She thought she was a literary rival, someone to be wary of, not quite trusted, and never to be fooled by her appearance, especially those big brown eyes, the severe bangs in a line across her forehead, her school marmish uniform, or the way she sat crossed-legged and drank tea out of bowls. Mansfield frightened Virginia, and it was only after Katherine’s early death in 1923 (a hemorrhage caused by running up a flight of stairs), and the subsequent publication of her journal, did Woolf see that Katherine Mansfield wasn’t a rival but her own distinct and brilliant talent.

Mansfield’s journal contained a heartbreaking tales of hardship, poverty, and debilitating illness. Woolf was shocked that Katherine had achieved so much against such very terrible odds. Virginia noted in her own journal how she would think about Katherine for the rest of her days. She did more than that, Woolf was directly influenced by Mansfield’s Modernist short stories and tried her own hand at Modernism with Mrs Dalloway, To the LIghthouse, The Waves and Between the Acts.

Mansfield’s Journal contained many short notes, ideas, descriptions and oblique details of her life - situations were often ill-defined, people disguised by initials, and important events missing - she destroyed much. Originally, the Journal had been edited for publication by John Middleton Murry, her indifferent husband and part-time lover, who literally abandoned Mansfield at the time of her greatest need. It was for him that she ran up those fatal stairs. Murry was a selfish, ineffectual and weak man, who exploited others to maintain a fantasy of his own genius - his books are lifeless, poorly written and dull. Woolf saw through him, and this may have clouded her judgment on Mansfield.

That’s the unfortunate thing about relationships, too often individuals can be limned by their other half. Mansfield was fiesty, brilliantly intelligent, and a very real talent, compared to Murry’s straw man.

There is a story in the Journal which is heartbreaking, and sad. And though not really about Mansfield, it in part mirrors something about the worst parts of relationships. Where Katherine suffered Murry’s damning indifference and torturous infidelities, the Cook of this tale suffered in a more brutal way.

I want to share it, because I think we can often judge too quickly, and too harshly, without ever knowing how another lives.

The Cook.

The cook is evil. After lunch I trembled so that I had to lie down on the sommier - thinking about her. I meant - when she came up to see me - to say so much that she’d have to go. I waited, playing with the wild kitten. When she came, I said it all, and she said how sorry she was and agreed and apologised and quite understood. She stayed at the door, plucking at a d’oyley. “Well, I’ll see it doesn’t happen in future. I quite see what you mean.”

So the serpent slept between us. Oh! why won’t she turn and speak her mind. This pretence of being fond of me! I believe she thinks she is. There is something in what L.M. says: she is not consciously evil. She is a FOOL, of course. I have to do all the managing and all the explaining. I have to cook everything before she cooks it. I believe she thinks she is a treasure…no, wants to think it. At bottom she knows her corruptness. There are moments when it comes to the surface, comes out, like a stain, in her face. Then her eyes are like the eyes of a woman-prisoner - a creature looking up as you enter her cell and saying: ‘If you’d known what a hard life I’ve had you wouldn’t be surprised to see me here.’

[This appears again in the following form.]

Cook to See Me.

As I opened the door, I saw her sitting in the middle of the room, hunched, still…She got up, obedient, like a prisoner when you enter a cell. And her eyes said, as a prisoner’s eyes say, “Knowing the life I’ve had, I’m the last to be surprised at finding myself here.”

The Cook’s Story.

Her first husband was a pawnbroker. He learned his trade from her uncle, with whom she lived, and was more like her big brother than anything else from the age of thirteen. After he had married her they prospered. He made a perfect pet of her - they used to say. His sisters put it that he made a perfect fool of himself over her. When their children were fifteen and nine he urged his employers to take a man into their firm - a great friend of his - and persuaded them; really went security for this man. When she saw the man she went all over cold. She said, Mark me, you’ve not done right: no good will come of this. But he laughed it off. Time passed: the man proved a villain. When they came to take stock, they found all the stock was false: he’d sold everything. This preyed on her husband’s mind, went on preying, kept him up at night, made a changed man of him, he went mad as you might say over figures, worrying. One evening, sitting in the chair, very late, he died of a blood clot on the brain.

She was left. Her big boy was old enough to go out, but the little one was still not more than a baby: he was so nervous and delicate. The doctors had never let him go to school.

One day her brother-in-law came to see her and advised her to sell up her home and get some work. All that keeps you back, he said, is little Bert. Now, I’d advise you to place a certain sum with your solicitor for him and put him out - in the country. He said he’d take him. I did as he advised. But, funny! I never heard a word from the child after he’d gone. I used to ask why he didn’t write, and they said, when he can write a decent letter you shall have it - not before. That went on for twelvemonth, and I found afterwards he’d been writing all the time, grieving to be taken away. He’d done the most awful things - things I couldn’t find you a name for - he’d turned vicious - he was a little criminal! What his uncle said was I’d spoiled him, and he’d beaten him and half starved him and when he was frightened at night and screamed, he turned him out into the New Forest and made him sleep under the branches. My big boy went down to see him. Mother, he says, you wouldn’t know little Bert. He can’t speak. He won’t come near anybody. He starts off if you touch him; he’s like a wild beast. And, oh dear, the things he’d done! Well, you hear of people doing those things before they’re put in orphanages. But when I heard that and thought it was the same little baby his father used to carry into Regent’s Park bathed and dressed of a Sunday morning - well, I felt my religion was going from me.

I had a terrible time trying to get him into an orphanage. I begged for three months before they would take him. Then he was sent to Bisley. But after I’d been to see him there, in his funny clothes and all - I could see ‘is misery. I was in a nice place at the time, cook to a butcher in a large way in Kensington, but that poor child’s eyes - they used to follow me - and a sort of shivering that came over him when people went near.

Well, I had a friend that kept a boarding house in Kensington. I used to visit her, and a friend of hers, a big well-set-up fellow, quite the gentleman, an engineer who worked in a garage, came there very often. She used to joke and say he wanted to walk me out. I laughed it off till one day she was very serious. She said, You’re a very silly woman. He earns good money; he’d give you a home and you could have your little boy. Well, he was to speak to me next day and I made up my mind to listen. Well, he did, and he couldn’t have put it nicer. I can’t give you a house to start with, he said, but you shall have three good rooms and teh kid, and I’m earning good money and shall have more.

A week after, he come to me. I can’t give you any money this week, he says, there’s things to pay for from when I was single. But I daresay you’ve got a bit put by. And I was a fool, you know, I didn’t think it funny. Oh yes, I said, I’ll manage. Well, so it went on for three weeks. We’d arranged not to have little Bert for a month because , he said, he wanted me to himself, and he was so fond of him. A big fellow, he used to cling to me like a child and call me mother.

After three weeks was up I hadn’t a penny. I’d been taking my jewels and best clothes to put away to pay for him until he was straight. But one night I said, Where’s my money? He just up and gave me such a smack in the face I thought my head would burst. And that began it. Every time I asked for money he beat me. As I said, I was very religious at the time, used to wear a crucifix under my clothes and couldn’t go to bed without kneeling by the side and saying my prayers - no, not even the first week of my marriage. Well, I went to a clergyman and told him everything and he said, My child, he said, i am very sorry for you, but with God’s help, he said, it’s your duty to make him a better man. You say your first husband was so good. Well, perhaps God has kept this trial for you until now. I went home - and that very night he tore my crucifix off and hit me on the head when I knelt down. He said he wouldn’t have me say my prayers; it made him wild. I had a little dog at the time I was very fond of, and he used to pick it up and shout, I’ll teech it to say its prayers, and beat it before my eyes - until - well, such was the man he was.

Then one night he came in the worse for drink and fouled the bed. I couldn’t stand it. I began to cry. he gave me a hit on the ear and I feel down, striking my head on the fender. When I came to, he was gone. I ran out into the street just as I was - I ran as fast as I could, not knowing where I was going—just dazed—my nerves were gone. And a lady found me and took me to her home and I was there three weeks. And after that I never went back. I never even told my people. I found work, and not till months after I went to see my sister. Good gracious! she says, we all thought you were murdered! And I never see him since…

Those were dreadful times. I was so ill, I could scarcely hardly work and of course I couldn’t get my little boy out. He had grown up in it. And so I hard to start all over again. I had nothing of his, nothing of mine. I lost it all except my marriage lines. Somehow I remembered them just as I was running out that night and put them in my boddy - sort of an instinct as you might say.

An edited version of Journal of Katherine Mansfield is available here, and her brilliant Collected Short Stories are available here and here. A documentary on Katherine Mansfield’s life can be viewed here.