Six years before Alejandro Jodorowsky’s extraordinary but ill-fated 1975 attempt to film Frank Herbert’s Dune—the story of which was compellingly told in the recent documentary Jodorowsky’s Dune—there was another similarly ambitious and ground-breaking film project that, until recently, was largely unknown.

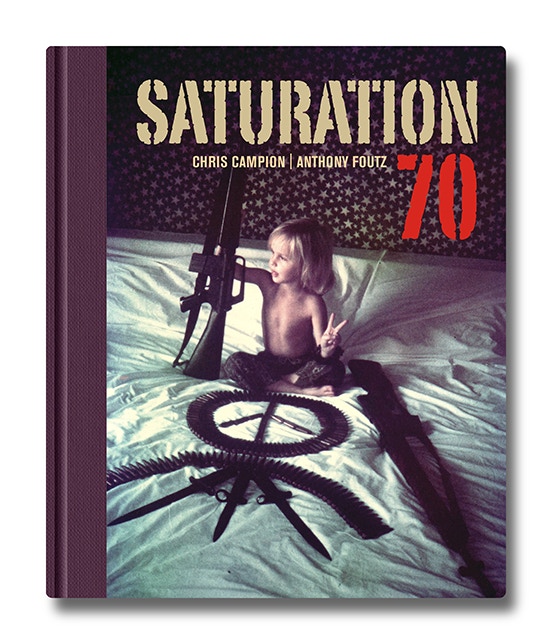

Saturation 70 was a special effects-laden science fiction movie starring Gram Parsons, Michelle Phillips of the Mamas and the Papas and Julian Jones, the five-year-old son of Rolling Stone Brian Jones. Unlike Dune, Saturation 70 did actually make it into production and was shot, but never completed, then was forgotten and undocumented for over forty years.

The film was written and directed by Tony Foutz, who crops up in several music histories, usually described as a ‘Stones insider’, but was actually much more than that. His father, Moray Foutz, was an early executive at Walt Disney. The younger Foutz had his own equally fascinating career path, working in the mid-sixties as a first assistant director in Italy for Gille Pontecorvo, Orson Welles and Marco Ferreri – for whom he later wrote Tales of Ordinary Madness, the first film adaptation of Charles Bukowski’s work. His connection to the Stones came via Anita Pallenberg, who he met in Rome during the filming of Roger Vadim’s Barbarella at Cinecitta Studios in the summer of 1967. Through her, he also befriended Keith Richards.

In 1968, while staying at Richards’ Redlands estate, Foutz wrote a script entitled Maxagasm in collaboration with Sam Shepard, for himself to direct as a vehicle for the Rolling Stones, who were to star in the movie and produce an original soundtrack album for it. During pre-production for Maxagasm in Los Angeles, Foutz was tipped off about Integratron designer and space devotee George Van Tassel’s ‘Spaceship Convention’ at Giant Rock, near Joshua Tree, an annual gathering of UFO abductees and alien enthusiasts. Foutz gathered up some friends to go and film documentary footage there, intending to use it as a way of testing out special effects he was planning for Maxagasm.

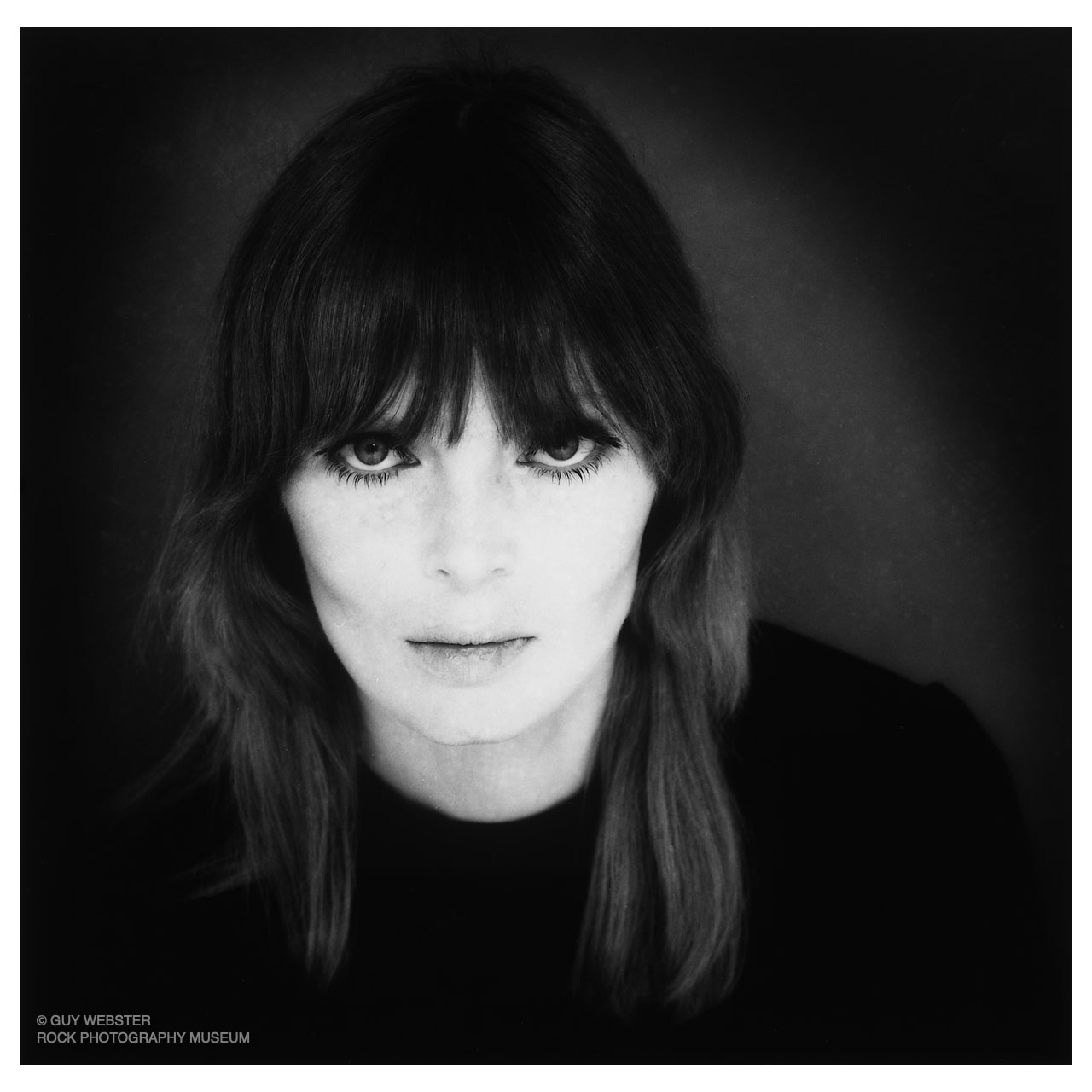

Gram Parsons at the piano in the lobby of the Chateau Marmont, 1970. Still from the ‘Saturation 70’ promo reel (Anthony Foutz Archive).

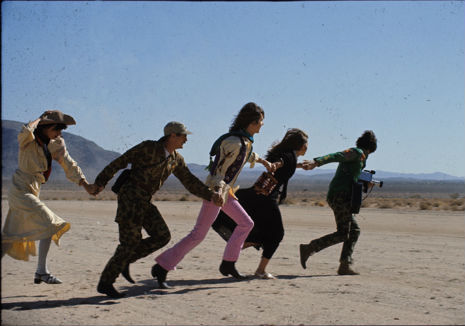

On that trip were Gram Parsons (Foutz’s roommate at the Chateau Marmont), Michelle Phillips, Julian Jones and his mother, Linda Lawrence (Parsons’ then-girlfriend), rock photographer Andee Cohen, Flying Burrito Brothers roadie Phil Kaufman, and western character actor Ted Markland—known as ‘the Mayor of Joshua Tree’ for his role in popularizing the location as a retreat for the hip Hollywood set. (It was Markland who first took Lenny Bruce, then the Stones, Parsons and Foutz to the desert to imbibe psychedelics and sit under the stars, scanning the sky for UFOs.) Also along for the ride were cinematographer Bruce Logan and special effects maestro Douglas Trumbull, both fresh off working on Stanley Kubrick’s 2001.

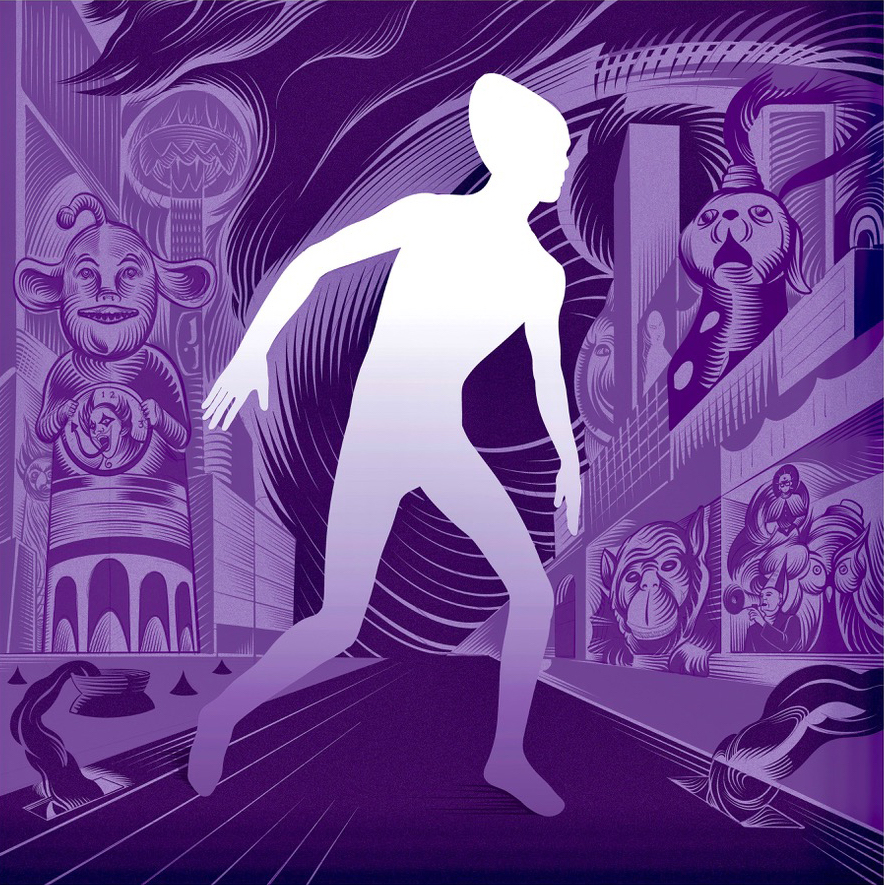

Fired up his experience at Giant Rock, Foutz decided to incorporate the footage they’d shot into another feature film project, that came together as a kind of counter culture version of the Wizard of Oz, about a lost star child (Julian Jones) who falls through a wormhole into present day Los Angeles and tries to find his way back home, assisted by four alien beings—the Kosmic Kiddies—who wear clean suits to protect them from the pollution. (The title of the film referenced the level at which carbon monoxide in human blood becomes lethal.)

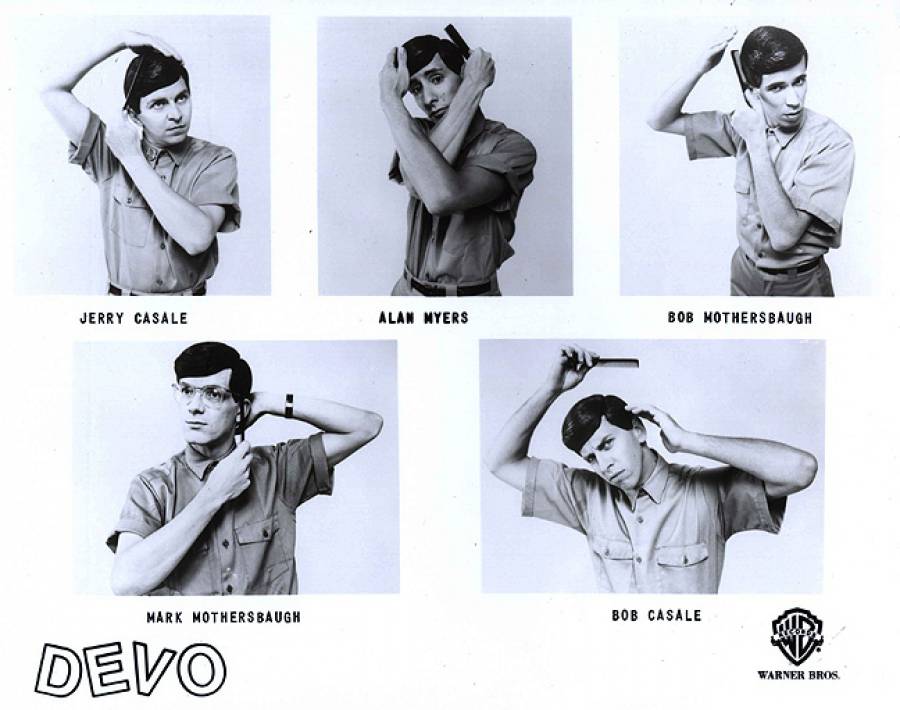

The Kosmic Kiddies, from R to L: Tony Foutz, Michelle Phillips, Gram Parsons, Phil Kaufman and Andee Cohen. Photo: Tom Wilkes

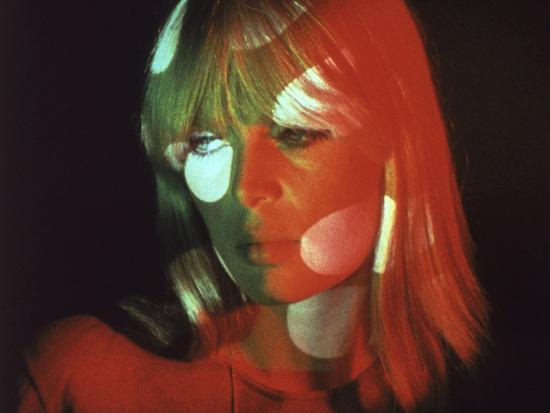

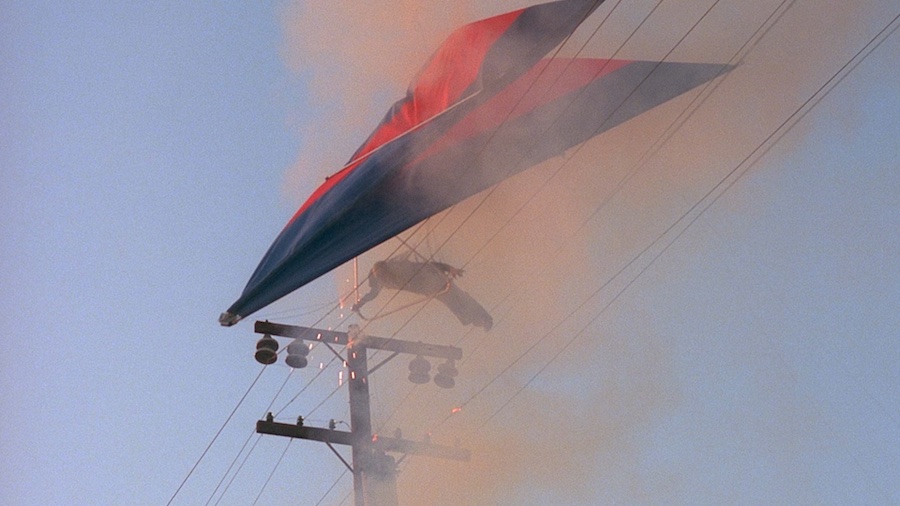

Saturation ’70 was shot in and around Los Angeles from October 1969 through spring of 1970 and included several spectacular set pieces: a surreal shootout between a Viet Cong soldier and an American G.I. in the aisles of Gelson’s supermarket in Century City (noted gun fan, Phil Spector, visited the set that day and stood on the sidelines to watch); a cowboy picnic on the Avenue of the Stars featuring country music couturier Nudie Cohn and a bevy of cowgirl cheerleaders; and a parade of Ford Edsel cars roaring through the City of Industry in a flying V-formation. He also filmed the Kosmic Kiddies roaming around the city in their clean suits and masks—inside them, Gram Parsons, Michelle Phillips, Stash Klossowski de Rola (the son of painter Balthus) and Andee Cohen.

Seeing an opportunity for cross promotion with his music career, Parsons had the Flying Burrito Brothers wear the same suits on the cover of their second album, Burrito Deluxe (also named in honor of the working title for Foutz’s script, “Rutabaga Deluxe”). Parsons and Roger McGuinn were brought together to write songs for and score the soundtrack. Rolling Stone would report that McGuinn intended to use the Moog synthesizer he had acquired at the Monterey Pop Festival two years earlier.

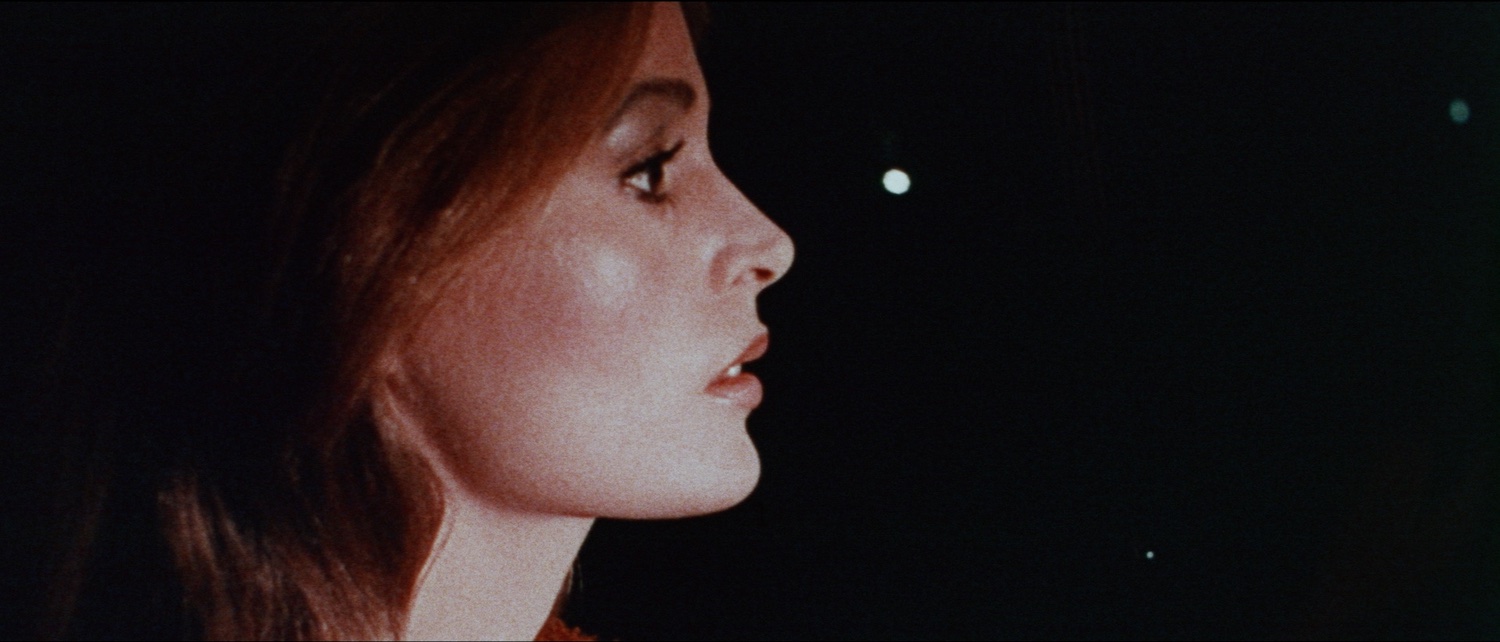

Julian Jones and his fairy godmother

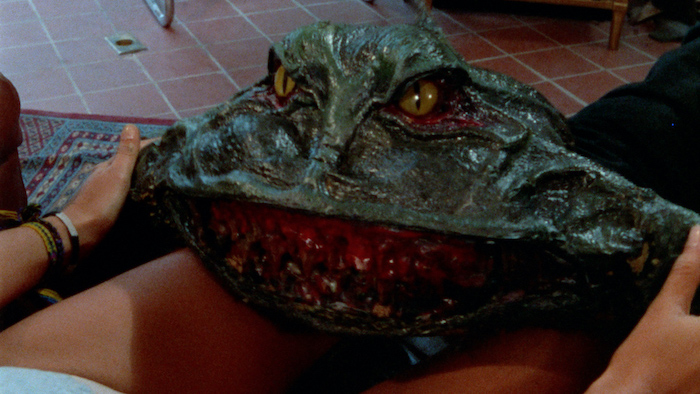

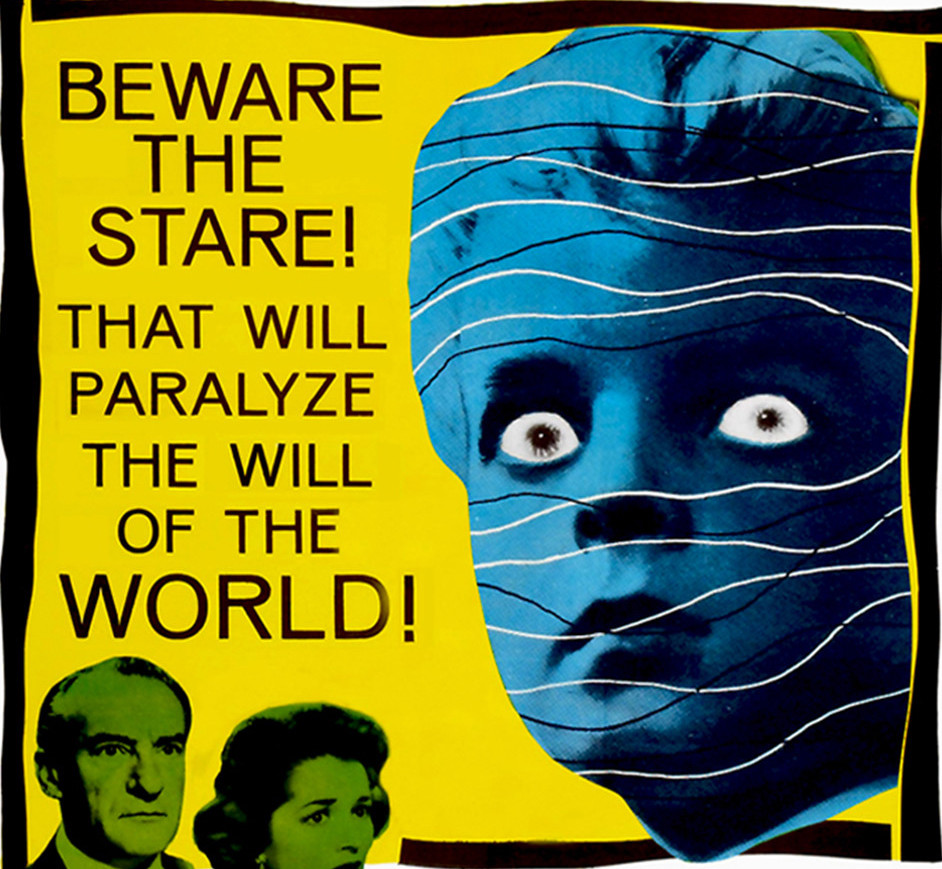

Once principal photography was complete, Foutz started working on the special effects sequences at Doug Trumbull’s Canoga Park facility, incorporating computer-processed visual effects Trumbull was developing there that allowed for graphic and textual overlays on pre-existing film images—a revolutionary idea at the time. Among the effects Foutz and Trumbull were working to create were propagandistic data clouds that floated in the sky (akin to the dirigibles later seen in Ridley Scott’s Blade Runner), towering skyscrapers made of television screens and dinosaurs roaming among the derricks in the Inglewood Oil Field near La Cienega Boulevard.

Skid Row Los Angeles, 1970. Not much has changed. Look closely at the signs.

However, before they could complete their work, funding for the film fell through, the producers abandoned the project and the entire project collapsed. All of the footage was subsequently lost apart from one five minute showreel cut to the Flying Burrito Brothers version of the Jagger/Richards song, “Wild Horses,” which Parsons had contributed to the writing of a few months earlier.

For years, existence of the film was little more than a rumour among Gram Parsons fans—a strange anomalous event in his short, gloried career—but now all the existing production photos have been dusted off for an upcoming book that recreates the film shoot, and the story of Saturation 70 can finally be told.

Preorder Saturation 70: A Vision Past of the Future Foretold HERE.