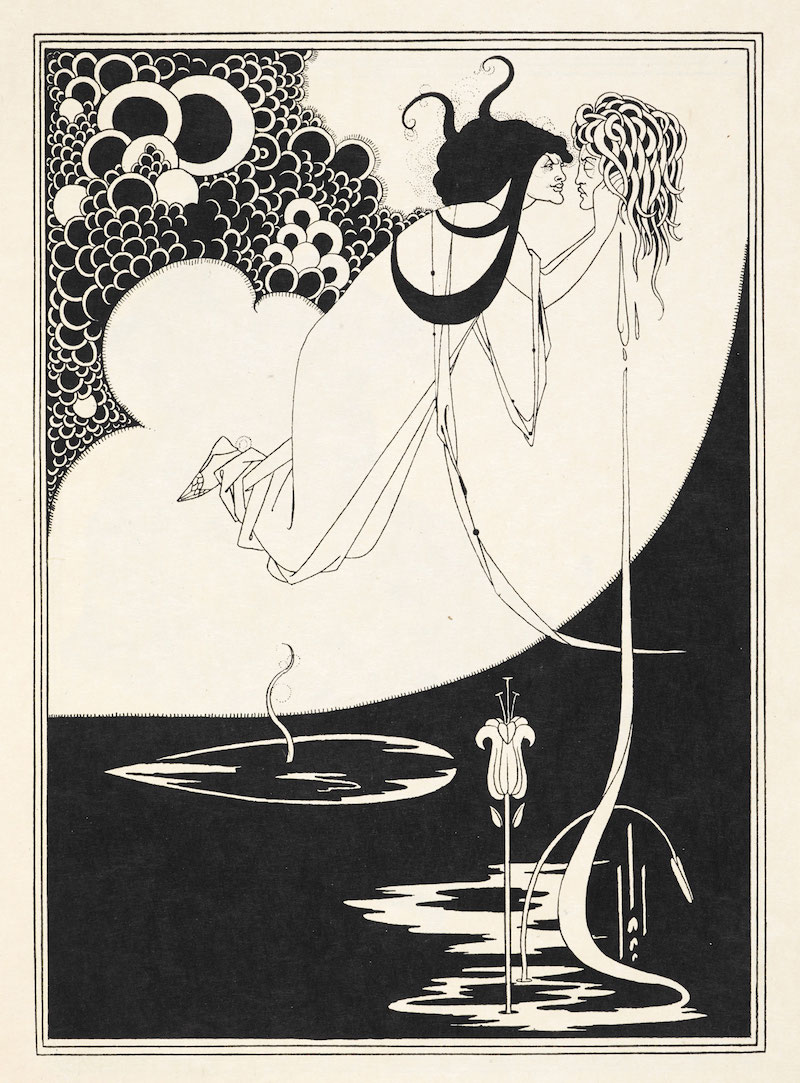

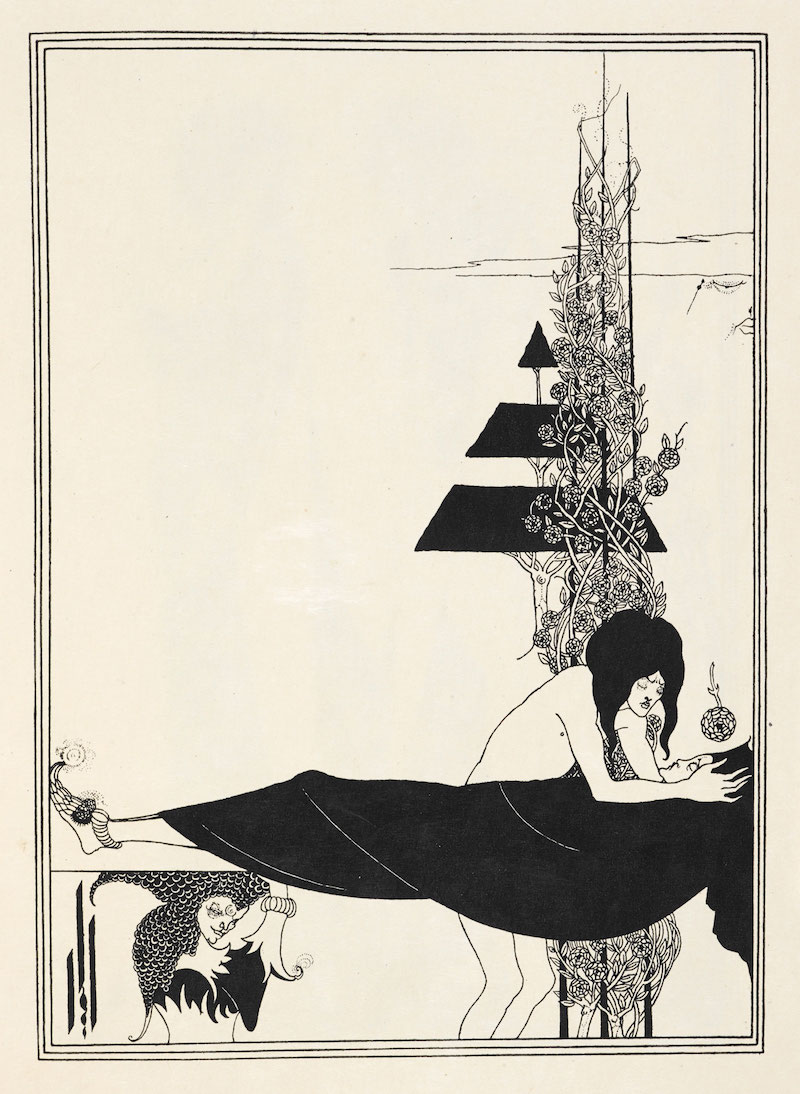

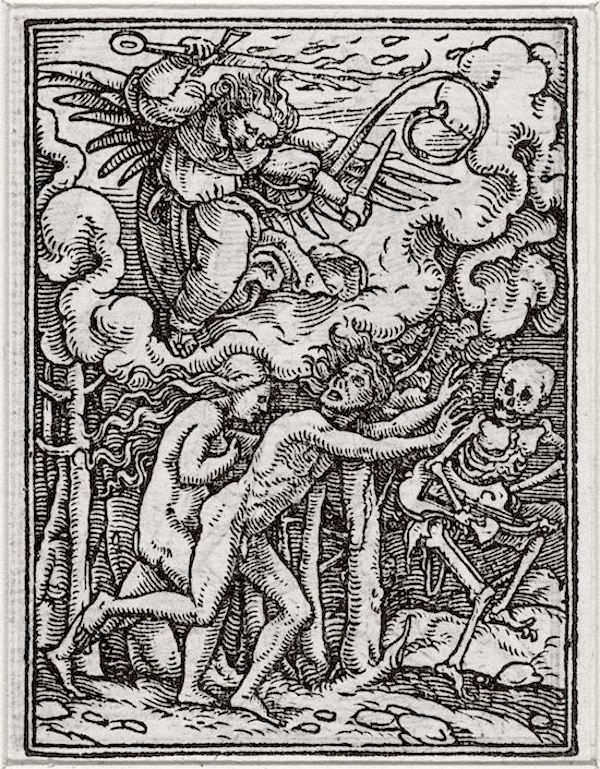

‘The Expulsion from Paradise.’

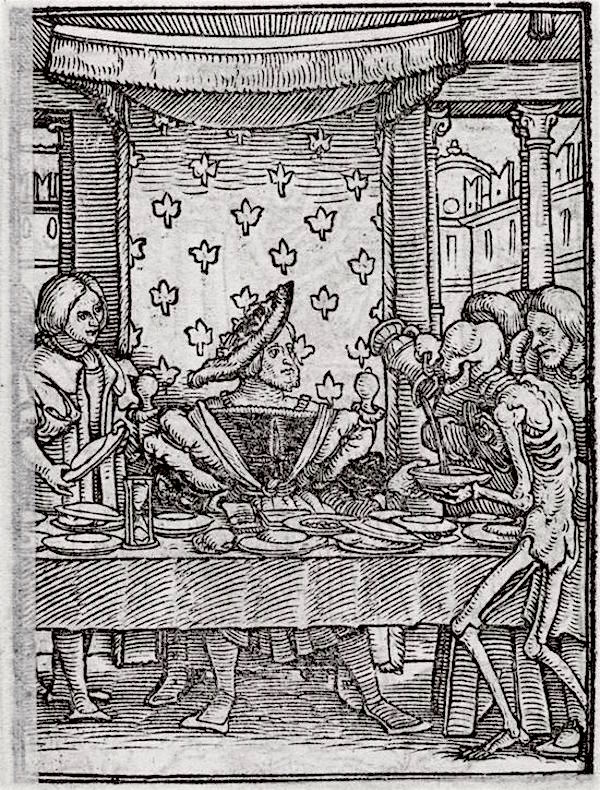

The miser’s gold won’t save him, nor the knight his belted armor, Death holds dominion over all and is indifferent to our pleading.

The story of Hans Holbein’s woodcut illustrations for The Dance of Death would fit snugly as a vehicle for Bill and Ted to explain the meaning behind these most excellent pictures with their bodacious representations of gnarly death playing a tune for all to follow into the grave. Cue air guitar riff. Which, Bill would add, is but a timely reminder to be most excellent to each other. And now here’s Hans Holbein (1497–1543) at San Dimas High explaining how his outstanding drawings were carved into wood by Hans Lützelburger, one of Holbein’s regular collaborators, who cut forty-one wood blocks before Death did call on him and lead swiftly him away.

But wait, let’s get an idea of size. These images are small, seriously small. Two-and-a-half inches by one-and-seven-eighths. The size of four postage stamps placed together to form a rectangle, as Ulinka Rublack notes in her excellent commentary in the Penguin edition of Holbein’s work. Fascinating she is too, as Rublack points out that these images came at a time of egregious turmoil when the Protestant Reformation was calling out the Catholic Church as most bogus and heinous and the Pope as ye AntiChrist. Think of this rising Protestant faith like emo Goths dressed in black, with a liking for The Cure and a bit death-obsessed. While the Catholic Church was like the New Romantics poncing about in fabulous costumes of silk and lace with a predilection for cardinals having a choirboy sitting on their cocks. This world was run by faith and disease. If the church didn’t punish you then the plague would.

The Protestants saw the Catholic faith as a false representation of Christ’s ministry on Earth. The Catholic Church was rich and corrupt. Its clergy indifferent, its flock abandoned (see the images of sheep wandering lost among the fields). The Church’s interest seemed more fixed on money (for indulgences, prayers, and masses to buy the rich a place in Heaven) rather than on souls. The Protestants wanted to bring the Church back to an austere faith based on the gospels. This is the background noise while Holbein worked on his pictures.

The idea of Death as some dancing skeleton was popularized by a 13th-century play The Three Dead and the Three Living, in which a band of three young noblemen while out hunting in the deep, dark forest came across three skeletons at three different stages of their journey. The story inspired a series of religious paintings and meditations of skeletons waiting to harvest the living. The skeleton unified everyone for one day we will all come to bone and dust. Once the image was set, the skeleton of Death soon had his victims dancing to his discordant tune.

And so it goes.

It’s not quite clear who exactly commissioned Holbein to produce these images. He was then an artist living in Basel with his wife and two children and the work was, no doubt, a welcome and lucrative commission. He produced his drawings between 1523 and 1525, which were intended to focus throughts towards God—-or at least Death. And like Death itself, Holbein’s deeply serious yet to our eye darkly satiric illustrations take aim at all classes of society—even the infant child is not spared the grisly clutch of Death.

‘The Pope.’

‘The Emperor.’

‘The King.’

More from Holbein’s ‘The Dance of Death,’ after the jump….