Have you ever received a letter from a friend you haven’t heard from for a while, or even an email? And then you wanted to respond right away but you wanted to do it right, not just dash something off, so you put it off a day, and the next time you thought of it, eight days had passed, and it became a thing where too much time had passed for you to write the reply straight, and you felt awkward about it, so you put it off some more, and then every day that passed made it harder to respond forthrightly? And then it turned into this odd kind of guilt, and you found yourself actually harboring hostile feelings towards your friend for having put you in that position in the first place?

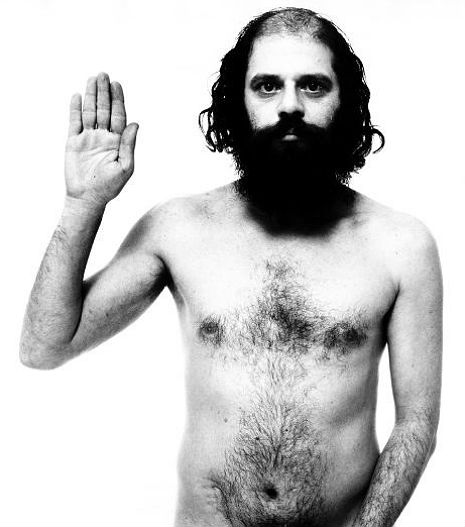

Has anything like that ever happened to you? Because something quite like that happened to Harlan Ellison on the most colossal scale imaginable. The nightmare was primarily of his own making, and he didn’t handle it at all well.

Before we get into this, Ellison is a tremendously talented and accomplished guy, and nothing I write here is intended to gainsay that premise. He’s also known for being kind of a difficult guy, and well, this story has a bunch of that.

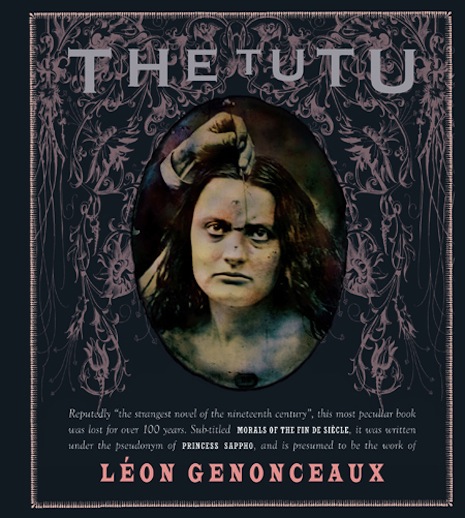

Strangely, this story revolves around a set of books that can be thought of as a kind of precursor to Dangerous Minds—the title of the project was almost identical. In addition to all of the tremendous short stories Ellison penned, one of the most impressive accomplishments on his C.V. was his involvement in publishing two highly influential and successful sci-fi anthologies. The first one was called Dangerous Visions (1967) and the second one was called Again, Dangerous Visions (1972). The debacle came when Ellison attempted to publish the third volume, which was to be called The Last Dangerous Visions. It was supposed to be published by about 1974 or so. At least 100 and maybe as many as 150 prominent and not-so-prominent sci-fi authors submitted stories with the expectation that something like that would happen.

They’re still waiting—the ones who are still alive, anyway. Actually, truth be told, they’re probably not expecting anything to happen. In short, The Last Dangerous Visions became something like the Moby-Dick of science-fiction circles for a decade or two at least.

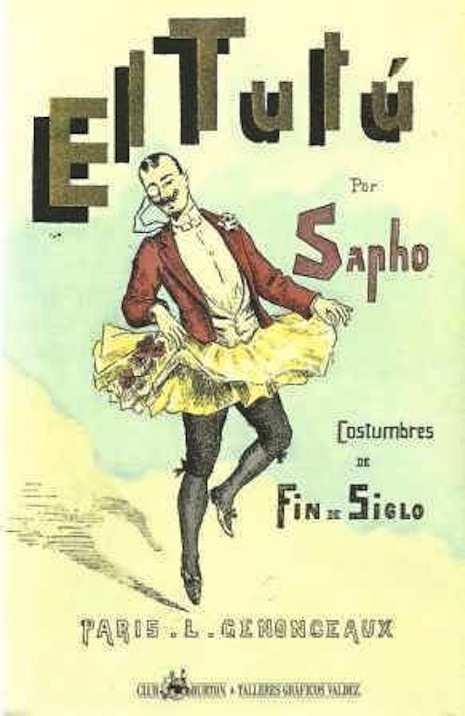

In the 1960s something special was brewing in the world of sci-fi. After having been a ghetto for dime-store practitioners for a generation or so (with a few exceptions), science fiction was on the verge of crossing over, breaking through, becoming real literature with a grown-up audience to match. The first Dangerous Visions featured talents as notable as Carol Emshwiller and J.G. Ballard and Philip K. Dick and Roger Zelazny and Samuel R. Delany and, of course, Ellison himself. It was a massive critical and commercial success, a true turning point for the genre. Five years later, Again, Dangerous Visions was also a hit, featuring Ursula K. Le Guin and Kurt Vonnegut and Piers Anthony and Ray Bradbury and Andrew J. Offutt and James Sallis and so on. By this time the Dangerous Visions books had entered the culture—they had an authentic audience who was eager to hear the details of the third volume. The literary brouhaha that would ensue wasn’t something that took place among a mere coterie, which gives the whole affair that much more bite.

xx971656156.jpg)

Dangerous Visions, 1967

The events surrounding the massive and ever-delayed third volume, to be called The Last Dangerous Visions, were described with great vitriol by Christopher Priest, a British sci-fi writer who was just starting his career around the time The Last Dangerous Visions started to be a thing, in a 1987 pamphlet called The Last Deadloss Visions (it was later published by Fantagraphics under the title The Book on the Edge of Forever, an allusion to Ellison’s Star Trek episode “The City on the Edge of Forever”). Priest submitted a story, and then at some point withdrew it from the anthology. For writers whose pay depended on the royalties from anthologies, one of the main undercurrents of the The Last Dangerous Visions affair is that the many stories Ellison collected for it were essentially trapped as long as he had them—the writers couldn’t really shop them around anywhere else, as they grew more dated and less relevant with every passing year.

The Last Deadloss Visions has existed in a couple different forms, but suffice to say that it’s very long and impassioned and well argued (you can read it on the Internet Archive).

xx918577626.jpg)

Again, Dangerous Visions, 1972

I’ll leave you to read it yourself—it takes an hour or so, and is well worth it—but I’ll divulge a few basic facts about it for those who don’t want to delve. What makes the situation surrounding The Last Dangerous Visions so jaw-dropping was the sheer scale of it—as many as 150 writers submitted stories, and by some calculations the number of words that the third book would have featured swelled as high as 1.3 million—this is twice as many as in War and Peace, or the same as perhaps an armful of regular-sized novels. According to Priest (his documentation is meticulous), Ellison on many occasions released statements to the effect that publication was just around the corner, he had “just dropped it off to the publisher” and so forth—none of which appears to have been true, and all of which had the effect of stringing the contributors along for another agonizing year or two. Ellison seems not to have behaved well in the affair, bullying, haranguing, and generally manipulating people, and even by 1975 or so—just three years—The Last Dangerous Visions had become something of a joke or an object of fascination in the sci-fi community. It’s the science fiction equivalent of Elastica’s second album, if you remember that length of that wait, although at least that album eventually was released. Lastly, I mentioned the death toll—which quickly became an index for the incredible time The Last Dangerous Visions was taking—by now the project is in its fourth decade, and the number of writers involved who have passed on to a different plane (according to Wikipedia) is forty-three.

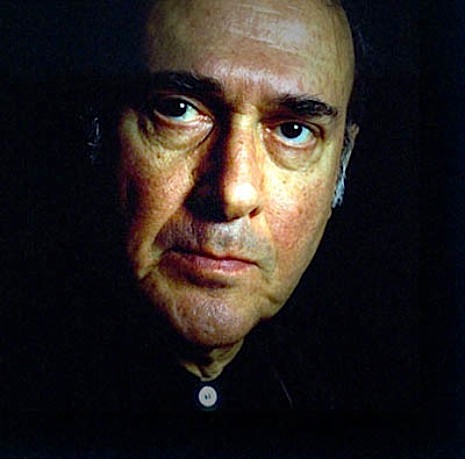

Remarkably, Ellison, who today is 79 years old, has stated as recently as 2007 that he intends to publish the book.

It still hasn’t happened.

Below, Isaac Asimov, Harlan Ellison and Gene Wolfe discuss science-fiction writing with Studs Terkel and Calvin Trillin on a program called Nightcap: Conversations on the Arts and Letters in 1982:

Posted by Martin Schneider

|

10.29.2013

01:18 pm

|

xx971656156.jpg)

xx918577626.jpg)