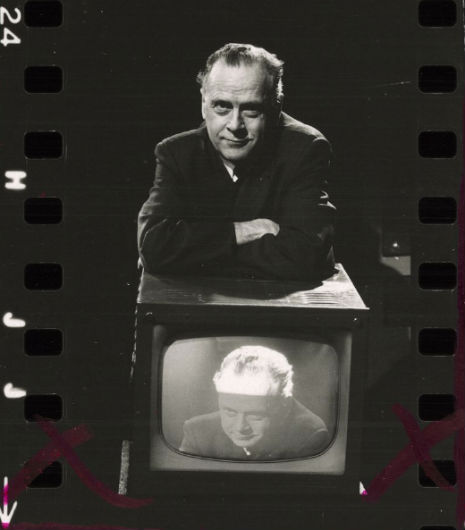

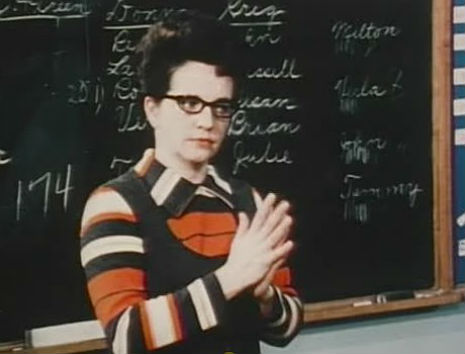

Marshall McLuhan explaining how the “one-liner” is symptomatic of the shortened attention-span of children. It’s all to do with television, which McLuhan claims, has a negative effect on the nervous system.

Marshall McLuhan explaining how the “one-liner” is symptomatic of the shortened attention-span of children. It’s all to do with television, which McLuhan claims, has a negative effect on the nervous system.

This is a guest post from Charles Hugh Smith. His newest book is Why Things Are Falling Apart and What We Can Do About It

Social recession is my term for the social and cultural consequences of a permanently recessionary economy such as that of Japan—and now, Europe and the U.S.

Forget Gross Domestic Product (GDP) as a measure of expansion (“growth”) or recession—what really matters is the social recession, which continues to deepen in America.

The term social recession has two distinct meanings: around 2000, the term was used to describe the erosion of social cohesion via the decline of institutions such as marriage and the rise of social problems such as teen pregnancy.

Many commentators pinned the responsibility for this erosion of social constraints and bonds on rampant individualism and overstimulated consumerism, while others pointed to urbanization, the commodification of child care, women entering the workforce en masse and similar trends. Poverty was explicitly rejected as a causal factor, hence the term “social recession.”

This notion of social recession was aptly described by Robert E. Lane, author of the 2001 book The Loss of Happiness in Market Democracies:

There is a kind of famine of warm interpersonal relations, of easy-to-reach neighbors, of encircling, inclusive memberships, and of solidary family life… For people lacking in social support of this kind, unemployment has more serious effects, illnesses are more deadly, disappointment with one’s children is harder to bear, bouts of depression last longer, and frustration and failed expectations of all kinds are more traumatic.

(For more on the subject, please see “The Social Recession” (The American Prospect.)

I use the term social recession to describe a very different phenomenon, the social and cultural consequences of permanently recessionary economies such as Japan, and now Europe and the U.S.

I have defined and used social recession in this way since 2010:

The Non-Financial Cost of Stagnation: “Social Recession” and Japan’s “Lost Generations” (August 9, 2010)

Here are the conditions that characterize social recession:

1. High expectations of endless rising prosperity have been instilled in generations of citizens as a birthright.

2. Part-time and unemployed people are marginalized, not just financially but socially.

3. Widening income/wealth disparity as those in the top 10% pull away from the shrinking middle class.

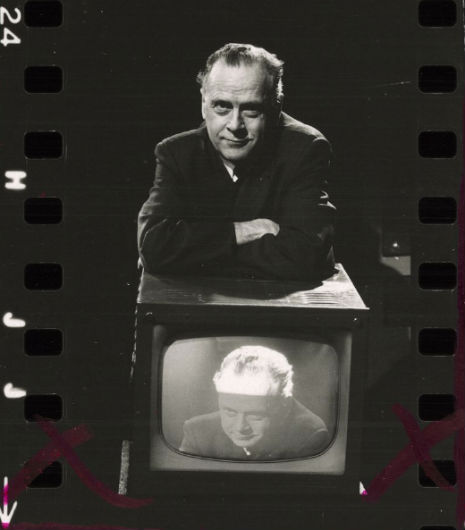

4. A systemic decline in social/economic mobility as it becomes increasingly difficult to move from dependence on the state (welfare) or parents to the middle class.

5. A widening disconnect between higher education and employment: a college/university degree no longer guarantees a stable, good-paying job.

6. A failure in the status quo institutions and mainstream media to recognize social recession as a reality.

7. A systemic failure of imagination within state and private-sector institutions on how to address social recession issues.

8. The abandonment of middle class aspirations by the generations ensnared by the social recession: young people no longer aspire to (or cannot afford) consumerist status symbols such as autos.

9. A generational abandonment of marriage, families and independent households as these are no longer affordable to those with part-time or unstable employment, i.e. the “end of work”.

10. A loss of hope in the young generations as a result of the above conditions.

I have described the “end to (paying) work” many times:

End of Work, End of Affluence (December 5, 2008)

End of Work, End of Affluence II: Cascading Job Losses (December 8, 2008)

End of Work, End of Affluence III: The Rise of Informal Businesses (December 10, 2008

Endgame 3: The End of (Paying) Work (January 21, 2009)

Demographics and the End of the Savior State (May 17, 2010)

What happens to the social fabric of an advanced-economy nation after a decade or more of economic stagnation?

For an answer, we can turn to Japan. The second-largest economy in the world has stagnated in just this fashion for almost twenty years, and the consequences for the “lost generations” which have come of age in the “lost decades” have been dire. In many ways, the social conventions of Japan are fraying or unraveling under the relentless pressure of an economy in seemingly permanent decline.

While the world sees Japan as the home of consumer technology juggernauts such as Sony and Toshiba and high-tech “bullet trains” (shinkansen), beneath the bright lights of Tokyo and the evident wealth generated by decades of hard work and the massive global export machine of “Japan, Inc,” lies a different reality: increasing poverty and decreasing opportunity for the nation’s youth.

The gap between extremes of income at the top and bottom of society—measured by the Gini coefficient—has been growing in Japan for years; to the surprise of many

outsiders, once-egalitarian Japan is becoming a nation of haves and have-nots.

The media in Japan have popularized the phrase “kakusa shakai,” literally meaning “gap society.” As the elite slice of society prospers and younger workers are increasingly marginalized, the media has focused on the shrinking middle class. For example, a bestselling book offers tips on how to get by on an annual income of less than three million yen ($30,770). Two million yen ($20,500) has become the de-facto poverty line for millions of Japanese, especially outside high-cost Tokyo.

More than one-third of the workforce is part-time as companies have shed the famed Japanese lifetime employment system, nudged along by government legislation which abolished restrictions on flexible hiring a few years ago. Temp agencies have expanded to fill the need for contract jobs, as permanent job opportunities have dwindled.

Many fear that as the generation of salaried Baby Boomers dies out, the country’s economic slide might accelerate. Japan’s share of the global economy has fallen below 10 percent from a peak of 18 percent in 1994. Were this decline to continue, income disparities would widen and threaten to pull this once-stable society apart.

Young Japanese, their expectations permanently downsized, are increasingly opting out of the rigid social systems on which Japan, Inc. was built.

The term “Freeter” is a hybrid word that originated in the late 1980s, just as the Japanese property and stock market bubbles reached their zenith. It combines the English “free” and the German “arbeiter,” or worker, and describes a lifestyle which is radically different from the buttoned-down rigidity of the permanent-employment economy: freedom to move between jobs.

This absence of loyalty to a company is totally alien to previous generations of driven Japanese “salarymen” who were expected to uncomplainingly turn in 70-hour work weeks at the same company for decades, all in exchange for lifetime employment.

Many young people have come to mistrust big corporations, having seen their fathers or uncles eased out of “lifetime” jobs in the relentless downsizing of the past twenty years. From the point of view of the younger generations, the loyalty their parents unstintingly offered to companies was wasted.

They have also come to see diminishing value in the grueling study and tortuous examinations required to compete for the elite jobs in academia, industry and government; with opportunities fading, long years of study are perceived as pointless.

In contrast, the “freeter” lifestyle is one of hopping between short-term jobs and devoting energy and time to foreign travel, hobbies or other interests.

As long ago as 2001, The Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare estimates that 50 percent of high school graduates and 30 percent of college graduates now quit their jobs within three years of leaving school.

The downside is permanently downsized income and prospects. Many of the four million “freeters” survive on part-time work and either live at home or in a tiny flat with no bath. A typical “freeter” wage is 1,000 yen ($10.25) an hour.

Japan’s slump has lasted so long, that a “New Lost Generation” is coming of age, joining Japan’s first “Lost Generation” which graduated into the bleak job market of the 1990s.

These trends have led to an ironic moniker for the Freeter lifestyle:

Dame-Ren (No Good People). The Dame-Ren get by on odd jobs, low-cost living and drastically diminished expectations.

The decline of permanent employment has led to the unraveling of social mores and conventions. Many young men now reject the macho work ethic and related values of their fathers. These “herbivores” also reject the traditional Samurai ideal of masculinity.

Derisively called “herbivores” or “grass-eaters,” these young men are uncompetitive and uncommitted to work, evidence of their deep disillusionment with Japan’s troubled economy.

A bestselling book titled The Herbivorous Ladylike Men Who Are Changing Japan by Megumi Ushikubo, president of Tokyo marketing firm Infinity, claims that about two-thirds of all Japanese men aged 20-34 are now partial or total grass-eaters. “People who grew up in the bubble era (of the 1980s) really feel like they were let down. They worked so hard and it all came to nothing,” says Ms Ushikubo. “So the men who came after them have changed.”

This has spawned a disconnect between genders so pervasive that

Japan is experiencing a “social recession” in marriage, births, and even sex, all of which are declining.

With a wealth and income divide widening along generational lines, many young Japanese are attaching themselves to their parents, the generation that accumulated home and savings during the boom years of the 1970’s and 1980’s. Surveys indicate that roughly two-thirds of freeters live at home.

Freeters “who have no children, no dreams, hope or job skills could become a major burden on society, as they contribute to the decline in the birthrate and in social insurance contributions,” Masahiro Yamada, a sociology professor wrote in a magazine essay titled, Parasite Singles Feed on Family System.

This trend of never leaving home has sparked an almost tragicomic counter-trend of Japanese parents who actively seek mates to marry off their “parasite single” offspring as the only way to get them out of the house.

An even more extreme social disorder is Hikikomori, or “acute social withdrawal,” a condition in which the young live-at-home person will virtually wall themselves off from the world by never leaving their room.

What we’re seeing in Japan is the confluence of three dynamics: definancialization, the demise of growth-positive demographics and the devolution of the consumerist model of endless “demand” and “growth.”

Japan is the leading-edge of the crumbling model of advanced neoliberal capitalism: that consumerist excess creates wealth, prosperity and happiness.

What consumerist excess actually creates is alienation, social atomization, narcissism,and a profound contradiction at the heart of the consumerist-dependent model of “growth”: the narcissism that powers consumerist lust and identity is at odds with the demands of the workplace that generates the income needed to consume.

Japan and the Exhaustion of Consumerism

The Hidden Cost of the “New Economy”: New-Type Depression

The Future of America Is Japan: Stagnation

The Future of America Is Japan: Runaway Deficits, Runaway Debts

The younger generation of workers raised in a consumerist “paradise” are facing an economic stagnation that reduces opportunities to earn the high income needed to fulfill the consumerist demands for status symbols. Given the hopelessness of earning enough to afford the consumerist lifestyle, they have abandoned traditional status symbols such as luxury autos and taken up fashion and media as expressions of consumerism.

But the narcissism bred by consumerism has nurtured a kind of emotional isolation and immaturity, what might be called permanent adolescence, which leaves many young people without the tools needed to handle criticism, collaboration and the pressures of the workplace.

Narcissism is the result of the consumerist society’s relentless focus on the essential project of consumerism, which is “the only self that is real is the self that is purchased and projected.”

Narcissism, Consumerism and the End of Growth (October 19, 2012)

In my analysis, this is the direct consequence of the supremacy of a consumerism that is dependent on financialization: an economy dependent on debt-fueled consumption to power its “endless growth” is one that will necessarily implode from its internal contradictions: debt and leverage eventually exceed the carrying capacity of the collateral and the national income, and the narcissism of consumerism leads to social recession, a crippling state of “suspended animation” adolescence and great personal frustration and unhappiness.

The ultimate contradiction in this debt-consumption version of capitalism is this: how can an economy have “endless expansion and growth” when pay and opportunities for secure, high-paying jobs are both relentlessly declining? It cannot. Financialization, consumerist narcissism and the end of growth are inextricably linked.

This leads to a dispiriting no exit:It’s as if there is a split in the road and no third way: some young people make it onto the traditional corporate or government career path, and everyone else is left in part-time suspended animation with few options for adult expression or development.

We need a third way that offers people work, resilience and authentic meaning. In my view, that cannot come from the Central State or the global corporate workplace: it can only come from a relocalized economy in revitalized communities.

For more on this topic:

Generational Wealth and Upward Mobility (October 24, 2012)

Priced Out of the Middle Class (June 28, 2012)

Do We Have What It Takes To Get From Here To There? Part 1: Japan (November 8, 2012)

Degrowth, Anti-Consumerism and Peak Consumption (May 9, 2013)

Tune In, Turn On, Opt Out (May 17, 2013)

Will Crushing Student Loans and Worthless College Degrees

Politicize the Millennial Generation? (May 31, 2013)

The Recession That Never Ended: 2008 -2013 (and Counting) (August 26, 2013)

This is a guest post from Charles Hugh Smith. His newest book is Why Things Are Falling Apart and What We Can Do About It

This is a guest editorial by Allan Sheahen, the author of the new book Basic Income Guarantee: Your Right to Economic Security (Palgrave/MacMillan, NYC). A previous essay from Mr. Sheahen, “Jobs are not the answer: The BIG idea that libertarians and socialists alike can agree on?” was published at Dangerous Minds last week and proved to be very popular.

America is awash with money.

Yet poverty continues to grow.

Does anybody care?

The latest government figures show that 46 million Americans live in poverty, more than at any other time in our nation’s history. That’s 15.1 percent of our population. One in five children live below the poverty line of $22,314 for a family of four, compared to one in twelve in France and one in 38 in Sweden.

Yet whenever elected officials ask their constituents what issues are most important to them, poverty isn’t even on the list. The economy, jobs, Afghanistan, the environment, health care, and education always show up. But not poverty.

Accordingly, Congress is now debating not whether to cut food stamps for the poorest Americans, but by how much. The Senate is proposing $4 billion in cuts. The House wants to cut $20 billion. Many Democrats are supporting the Senate version.

More than a half-million people are homeless in America. Food banks and homeless shelters are serving more people now than a year ago. Unemployment is at 7.6 percent.

The problem is that all the private charities in America can’t end hunger and poverty. Ending poverty demands government programs, such as Social Security, unemployment compensation, Medicare, welfare, food stamps, child care, and more.

The 1996 Welfare Reform Act was sold to us as a way to get people off welfare, and it did. Welfare rolls in the United States are down more than 50 percent. But it didn’t reduce poverty. That’s because welfare reform dumped many recipients into low-paying jobs—with no benefits or ability to move up.

Does anybody care?

Maybe we care, but we don’t know what to do about it. So we shrug, say the poor will always be with us, and forget about it.

In 1969, a Presidential Commission recommended we establish a Basic Income Guarantee (BIG) at the poverty level for all Americans.

On that Commission, the chairmen of IBM, Westinghouse, and Rand, former California Gov. Edmund G. (Pat) Brown and 17 others unanimously agreed with economist Milton Friedman that: “We should replace the ragbag of welfare programs with a single, comprehensive program of income suplements in cash—a negative income tax. It would provide an assured minimum to all persons in need, regardless of the reasons for their need.”

Fast-forward 44 years, and we find that welfare has failed because it has destroyed people’s ability to take control of their own lives and make their own decisions. We assume the poor are incapable of making sound decisions; that they can’t be trusted with cash and have to be protected from themselves. It’s as if your employer thought you so irresponsible that he sent part of your paycheck to your landlord, another part to your grocer, another to the bank that provided your car loan, another to your doctor.

There are more than 300 income-tested social programs costing more than $400 billion a year. Much of that money goes for administrative expenses, not to the needy.

Charles Murray, whose 1984 book Losing Ground claimed that welfare was doing more harm than good, now agrees with the BIG approach.

“America’s population is wealthier than any in history,” Murray writes in his new book, In Our Hands. “Every year, the American government redistributes more than a trillion dollars of that wealth to provide for retirements, health care, and the alleviation of poverty. We still have millions of people without comfortable retirements, without adequate health care, and living in poverty. Only a government can spend so much money so ineffectually. The solution is to give the money to the people.”

Murray calls for giving an annual cash grant of $10,000—with no work requirements—to every adult over age 21.

Indeed, the U.S. is a wealthy nation. Our 2011 Gross Domestic Product was $14.4 trillion. That’s an average of $46,000 for each man, woman and child in the country. It’s an average of $61,000 per adult. It’s more than enough to end poverty.

Poverty is wrong. A Basic Income Guarantee would establish economic security as a universal right. It gives each of us the assurance that, no matter what happens, we won’t go hungry.

Allan Sheahen is the author of the new book: Basic Income Guarantee: Your Right to Economic Security (Palgrave/MacMillan, NYC). For more information, go to www.basicincomeguarantee.com

Below, footage of FDR’s so-called “Second Bill of Rights” speech which was filmed right after he had finished his State of the Union Address on radio on January 11, 1944.

I was thrilled to see Allan Sheahen’s important essay on the BIG idea of the “Basic Income Guarantee” concept make it to the front page of Huffington Post recently, and I am pleased to be able to share it here with Allan’s blessing. I’ve long been a fan of the “Basic Income Guarantee” concept (which I was introduced to by Robert Anton Wilson) and this is as succinct an explanation of it as I have read anywhere. No surprise that it was shared so many times by Huffington Post readers.

As Mr. Sheahen explains below, the “Basic Income Guarantee” is a common sense solution to poverty that the likes of Libertarian economist Milton Friedman (overstating Friedman’s place of primacy in conservative economic orthodoxy would be difficult to do), liberal icon Senator George McGovern, Dr. Martin Luther King and even welfare critic Charles Murray could all agree upon.

That’s really saying somethin’, but I’ll let Allan explain…

Jobs Are Not the Answer

The current unemployment rate of 7.5 percent means close to 20 million Americans remain unemployed or underemployed.

Nobody states the obvious truth: that the marketplace has changed and there will never again be enough jobs for everyone who wants one—no matter who is in the White House or in Congress.

Fifty years ago, economists predicted that automation and technology would displace thousands of workers a year. Now we even have robots doing human work.

Job losses will only get worse as the 21st century progresses. Global capital will continue to move jobs to places on the planet that have the lowest labor costs. Technology will continue to improve, eliminating countless jobs.

There is no evidence to back up the claim that we can create jobs for everyone who wants one. To rely on jobs and economic growth does not work. We have to get rid of the myth that “welfare-to-work” will solve the problems of unemployment, poverty, and homelessness.

“Work” and jobs are not the answer to ending poverty. This has been the hardest concept for us to understand. It’s the hardest concept to sell to citizens and policy makers. To end poverty and to achieve true economic freedom, we need to break the link between work and income.

Job creation is a completely wrong approach because the world doesn’t need everyone to have a job in order to produce what is needed for us to live a decent, comfortable life.

We need to re-think the whole concept of having a job.

When we say we need more jobs, what we really mean is we need is more money to live on.

Basic Income Guarantee

One answer is to establish a basic income guarantee (BIG), enough at least to get by on—just above the poverty level—for everyone. Each of us could then try to find work to earn more.

A basic income would provide economic freedom and income security to everyone. We’d have the freedom to work less if we wanted to, or work the same amount and save or spend that money.

It would provide a direct stimulus to the economy, which would help create more jobs.

In 1972, Democratic presidential candidate and Senator George McGovern knew the economy was changing. He proposed a $1000 annual “demogrant” for every American. The grant would act as a kind of cushion against the loss of a job or other misfortune.

We could pay for a Basic Income Guarantee by eliminating most of the 20th-century programs like unemployment insurance, welfare, Social Security, Section 8 housing, etc., and by having the wealthy pay their fair share in taxes.

Billionaire Warren Buffett admits he pays a lower tax rate than his secretary. Mitt Romney said he paid only 13.9 percent in federal income tax in 2010, despite earning $22 million. Average-income Americans pay about 20 percent.

A BIG would be cheaper than a jobs program. President Obama’s 2009 stimulus plan promised to create 3 to 4 million jobs at a cost of $862 billion. That’s over $200,000 per job.

Such a basic income would recognize that with productivity as high as it is today, too many workers get in each other’s way. Those who don’t have to work shouldn’t be required to do so. Instead, they can create, do volunteer service, or work at low-paying jobs which are still socially needed, such as teaching or the arts.

Think of it as the opposite of trickle-down economics, where we give huge tax breaks to the rich in the false hope that something will trickle down to the rest of us.

Try telling a conservative blow-hard that their hero Milton Friedman was the architect of the most successful social welfare program in US history and they’ll often simply refuse to believe you! When offered proof, it seems to infuriate them.

Not a New Idea

Basic income is not a new idea. It’s been debated among policymakers in several nations since the 1970s. Economist Milton Friedman said: “We should replace the ragbag of specific welfare programs with a single comprehensive program of income supplements in cash—a negative income tax.”

The Reverend Martin Luther King, Jr., said: “I am convinced that the simplest solution to poverty is to abolish it directly by a guaranteed income.”

BIG’s most recent American advocate is welfare critic Charles Murray. In his book: In Our Hands, Murray agrees with Friedman and King, and proposes a $10,000 yearly grant paid to every adult. Murray and others argue it would save money. There would be no bureaucracy to support and no red tape to manage.

Opponents claim we shouldn’t pay people not to work. But the duty to pursue work is based on the mistaken assumption that there is work to be had.

In the post-industrial age, the USA will provide ever fewer opportunities for low-skilled workers. Policies in pursuit of full employment make no sense.

Basic Income Can Work

In 1982, the state of Alaska began distributing money from state oil revenues to every resident. The Alaska Permanent Fund gives about $1000 to $2000 each year to every man, woman, and child in the state. In 2012, the amount fell to $878. There are no work requirements. The grant has reduced poverty and the inequality of income in Alaska.

A 10-year, 7800-family, U.S. government test of a basic income in the 1970s found that most people would continue to work, even when their incomes were guaranteed. A test in Manitoba, Canada produced similar results.

In 2005, Brazil created a basic income for the most needy. When fully implemented, the plan will ensure that all Brazilians, regardless of their origin, race, sex, age, social or economic status, will have a monetary income enough to meet their basic needs.

A two-year, basic income pilot program just concluded in Otjivero, Namibia. Each of 930 villagers received 1000 Namibian dollars (US$12.40) each month. Malnutritition rates of children under five fell from 42 percent to zero. Droupout rates at the school fell from 40 percent to almost zero. It led to an increase in small businesses.

Most Americans are six months from poverty. Middle-class people who worked all their lives, then lost their jobs and saw their unemployment benefits expire, are now sleeping in parks and under bridges.

America hasn’t seen full employment in decades. Even a full-time job at the minimum wage can’t lift a family of three from poverty. Millions of Americans—children, the aged, the disabled—are unable to work.

A basic income guarantee would be like an insurance policy. It would give each of us the assurance that, no matter what happened, we and our families wouldn’t starve.

This has been a guest editorial courtesy of Allan Sheahen, committee member of the U.S. Basic Income Guarantee Network (USBIG) and author of the recently published book Basic Income Guarantee: Your Right to Economic Security .

Below, Allan Sheahen discusses the guaranteed income bill with Mark Crumpton on Bloomberg Television’s Bottom Line.

Snippets of this classic debate between Noam Chomsky and Michel Foucault have been wafting about online for ages, but I think it’s only been posted in full relatively recently, and is well, well worth a thorough viewing…

Which is not to say that it’s a great debate exactly. Initially, indeed, it’s a veritable orgy of awkwardness, resembling something like the worst blind date of all time. The interlocutors come across as chalk and cheese, both philosophically and personally. And despite a fair showing of professional courtesy in what they say, their expressions (while the other is talking) tell another story : Chomsky tending to eye Foucault as if the latter is a louche and ludicrous fraud, and seeming to be constantly having to swallow a smirk, while Foucault, accordingly, gazes at Chomsky as if near stupefied by the intellectual credulity of this American super-ninny.

There is some more elevated fun to be had here, too, mind. Both thinkers offer very lucid formulations of their fundamental outlook, and these outlooks do seem peculiarly, pointedly inverse, so much so in fact that for some time they can’t even seem to engage with one another (as is tediously emphasized by the strange Dutch commentator figure, who introduces it and then twice inexplicably bobs up to be incredibly boring straight at the camera for three or four minutes—just warning you about that one).

Once they get into the topics of morality and politics, however, the discussion comes to life, and so much so that, by the end, Chomsky’s looking at Foucault in an entirely different fashion—namely, as if the latter might just be some kind of moral monster.

Best of all though, is the audience, which seems composed entirely of members of krautrock group Can in various, slight, shifting disguises.

This is a guest post by Melissa Sweat from the DM archives. It seems timely again so we’re re-posting it

“It might be interesting to judge people today by the color of their eyes. Would you like to try this? Sounds like fun doesn’t it?” –Jane Elliott

The class of third graders are told that blue-eyed people are smarter and better than brown-eyed people. Blue-eyed people get an extra five minutes of recess, and the two groups aren’t allowed to play with one another on the playground. The brown-eyed children wear fabric collars so they can be identified from a distance. When, during recess, one of the children calls the other “brown-eyed” as an epithet and the child retaliates by slugging the taunter, Jane Elliott does what any good teacher would do: the child is reprimanded, but the overall exercise continues.

It was the day after Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated in 1968 that Elliott ran her first “Blue Eyes/Brown Eyes” exercise in her Riceville, Iowa classroom. In 1970, Elliott would come to national attention when ABC broadcast their Eye of the Storm documentary which filmed the experiment in action. Below, is a portion from the 1985 PBS Frontline documentary A Class Divided which features the ABC footage as well as clips of a class reunion.

Elliott would earn further renown appearing on The Tonight Show, The Oprah Winfrey Show and speaking at over 300 colleges and universities throughout her career. Her landmark exercise helped pioneer the field of diversity training and anti-racism education in which she still works to this day.

Watching Elliott perform her social experiment on her class of young children, it’s easy to notice her determined reserve—and also just how psychologically deep she’s treading as she instigates the discrimination amongst her students. One can’t help but wonder if an exercise this controversial would even fly in today’s classrooms, and how many parents back then might have complained that this lesson was too forward and inappropriate for their children. Perhaps they didn’t want their kids being taught outside the “three Rs” curriculum, or about the difficult subject of racism in such a fervent time. Maybe some thought it didn’t pertain to their small, all-white towns.

Certainly Elliott garnered criticism for teaching and treading against the grain, though her impact reached well beyond her Iowa classroom because of it.

This is a guest post by Melissa Sweat

Portrait of William S. Burroughs by AtelierBagatelle

“Art makes people aware of what they know and don’t know.”

William Burroughs said in this interview with (“pilot & writer”) Jürgen Ploog.

“Once the breakthrough has been made there’s a permanent expansion of awareness. But there’s always a reaction of outrage at the first breakthrough.

The artist expands awareness, and once the breakthrough is made, it becomes part of the general awareness.”

The conversation between the two men forms the basis of Klaus Meck’s documentary William S. Burroughs: Commissioner of Sewers. Filmed in what looks like a hotel room, the duo’s dialog is inter-cut with clips of Burroughs reading extracts from his work, including “The Do Goods” and “Advice for Young People.”

Ploog’s questions rather randomly move from writing (where Burroughs claims if he hadn’t succeeded getting his novel Junkie published, he might never have become a writer); to religion and reincarnation; through Cezanne and Art and onto animals (where WSB discusses why humans empathize more with predatory animals than with their prey). Their disjointed Q&A has a strange “episodic” quality to it but Burroughs (and his encyclopedic knowledge) is fascinating throughout.

Bonus track: Burroughs reads “When did I stop wanting to be President?” after the jump…

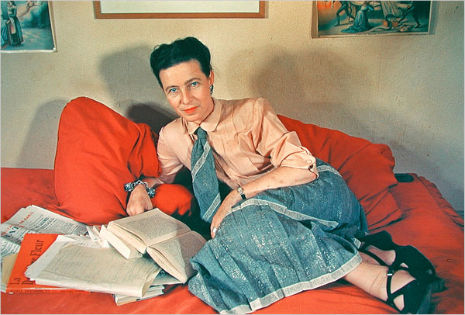

An exceptional interview with Simone de Beauvoir, from the French TV program Questionnaire, in which the great writer discussed her views on Feminism with Jean-Louis Servan-Schreiber.

Beginning with a quote from her book The Second Sex, de Beauvoir explained the meaning of her oft-quoted line, “One is not born a woman, one becomes one,”

“...being a woman is not a natural fact. It’s the result of a certain history. There is no biological or psychological destiny that defines a woman as such. She’s a product of a history of civilization, first of all, which has resulted in her current status, and secondly for each individual woman, of her personal history, in particular, that of her childhood. This determines her as a woman, creates in her something which is not at all innate, or an essence, something which has been called the ‘eternal feminine,’ or femininity. The more we study the psychology of children, the deeper we delve, the more evident it becomes that baby girls are manufactured to become women.”

Recorded in 1975, this interview is in French with English subtitles.

Michel Foucault: Beyond Good and Evil, director David Stewart’s superb 1993 portrait of the social theorist of power in history manages to squeeze a lot of information into its short 42 minutes and provides a pretty adequate introduction to Foucault’s life and work.

Foucault’s acid trip at Zabriskie Point watching the sun set over Death Valley listening to Stockhausen (which the philosopher described as the greatest experience of his life) is recreated, as is a 1947 performance of Antonin Artaud’s Theatre Of Cruelty. Foucault’s drug use, his participation in the sadomasochistic San Francisco leather scene and death from AIDS in 1984 at the age of 57 are also covered.

In various languages, but there are English subtitles when it’s necessary.

Yeah, it’s great that doctors can print casts and prosthetic legs and stuff, but to my mind, this is what 3-D printing was invented for…

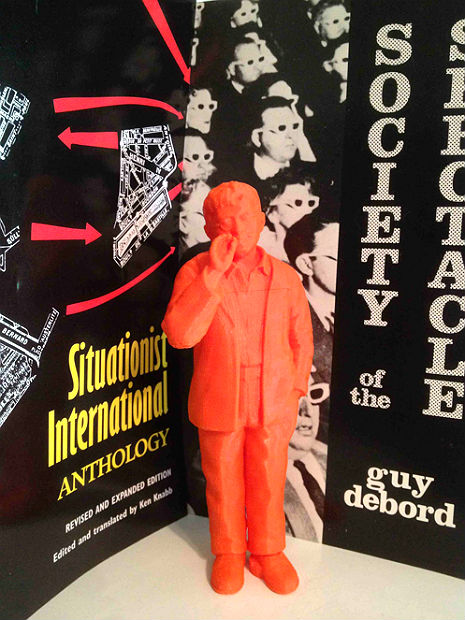

Behold cultural theorist Mackenzie Wark’s limited edition Guy Debord figurine. Two-hundred of these post-Marxist bad boys were printed up. The project was conceived and designed by Wark, Peer Hansen and Rachel L. Verso Books gave away one of them to promote Wark’s new book, The Spectacle of Disintegration: Situationist Passages out of the Twentieth Century.

If you happen to own a 3-D printer, or have access to one, you can download the plans for your own 3-D Guy (that rhymes, btw), here, as the plans were released under a Creative Commons license. Rather predictably, Wark’s clever publicity stunt brought on humorless protest from Situationist-types.

There’s also a remixed version of the Debord figurine with Stelarc’s 3rd Ear on his back and Eduardo Kac’s infamous “Alba” bunny ears. That one you’d probably want to print up in fluorescent lime green…

Imagine a Lenny Bruce action figure, or Robert Anton Wilson, Wittgenstein, Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone de Beauvoir, Samuel Beckett, Grace Slick, James Joyce, Vivian Stanshall, Orson Welles, Nico… I’m sure they’re all on their way soon.