First of all, let’s face it, there is no way to overestimate Ministry’s influence on rock ‘n’ roll. For one brief moment in time (let’s say 1988), they were the heaviest band on the planet, and they are clearly the greatest industrial-rock band of all time (unless you include fire tricks, then obviously Rammstein). And probably the best part about it is that they’ve been shepherded for the past thirty-something years by a complete maniac.

“God, I hate that guy. And he owes me an ass-fuck.”

- Al Jourgensen on Robert Plant

Frontman/chief-strategist/visionary Al Jourgensen started Ministry in Chicago in 1981. Originally they were a soppy synth-pop band (see 1983’s With Sympathy album, still a dancefloor fave among less sociopathic new-wavers), but as the 80s wore on, the drugs and the guitars and the psychiatric disorders took hold and by 1987’s Land of Rape and Honey album, the sound and vision had evolved into an ear-bleeding digital acid-metal nightmare. Shows became war zones. The band ushered in the 90s with hardcore sex and violence and enough Marshall stacks to topple the New World Order. Throughout it all, Jourgensen crawled through the muck of his own tortured psyche, drowning his psychosis with more psychosis in an endless orgy of sex, drugs and debauchery. And in 2013, he spilled the beans in a tell-all autobio, The Lost Gospels According to Al Jourgensen, that would swear even the most hardened drug enthusiast into a life of quiet sobriety. I mean, this is how the goddamn book starts:

“All that came out of me was blood, and there was so much pouring out of my dick and asshole that I started to panic. I didn’t want the toilet to overflow, so I took off the helmet, held it to my ass, and let the blood pour in there. I fell off the toilet and I tried to put the helmet back on, and about twelve ounces of blood matted down my hair and ran down my face, pooling with the blood that was dribbling out of my face and nose.”

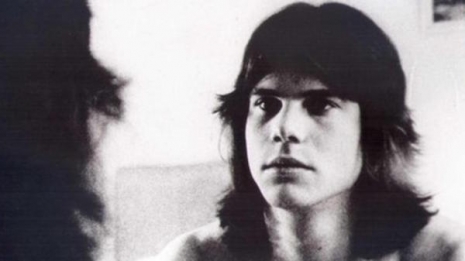

A Young Al Jourgensen (with Stephen “Stevo” George) in his pre-pissing blood pretty boy days

Given that audacious opener, you may be expecting a redemption story. Well, he eventually gets his teeth fixed, but that’s about it. Mostly it’s just full-tilt gonzo, all the time. Just ask Butthole Surfers’ megaphone abuser Gibby Haynes, who is no stranger to bad craziness himself. Touring with Ministry was heavy even for him.

“I had never really done that, where it was girls, hotel rooms, girls, blowjobs. There were so many girls and so many drugs, so much nudity. I was lying on the floor, and Al glanced over at me and went, ‘Nice cock, Haynes.’ I was like, ‘Aw man, no one’s ever told me that before.’ That’s so sweet. It might not be true, but it’s nice to hear.”

Hayne is not exaggerating, either. There’s an incredible amount of really weird, gross group sex on display in this book, most of it involving Jourgensen, it being his autobiography and all.

“One night I fucked a paraplegic chick in a wheelchair. I think she had Parkinson’s. So she’s blowing a guy in our crew and I’m fucking her. She’s wearing a colostomy bag, and I was naturally curious. I stopped fucking her for a second and I started squeezing the bag back into her.”

And as soon as the fucking is over, the drugs, booze, paranoia and craziness starts back up. And it’s not just Jourgensen. Most of his cohorts are just as nuts. Here’s a snapshot from the book of life with Pigface/Ministry singer Chris Connolly:

“One day Chris comes running over, sweating and all freaked out, saying skinheads attacked him. I grabbed some pepper spray and a baseball bat; I didn’t have a gun back then. I go running outside to confront these skinheads who harassed my new vocalist. It was two ten-year-olds on their bikes. I asked him, ‘is that what harassed you?’ And he said yeah. I was like, “They’re ten-year-olds with tennis rackets. I don’t waste pepper spray on ten-year-olds.”

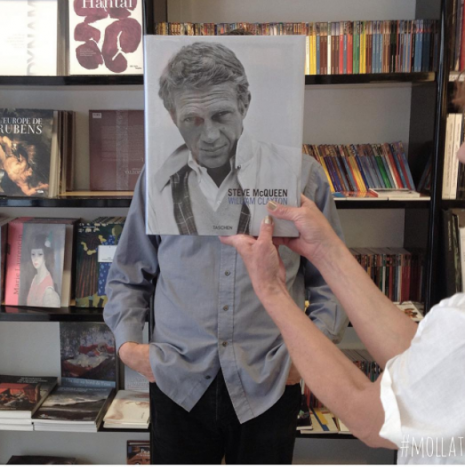

El Duce, only just slightly more epically fucked than the guy from Ministry

He also spent more time with Mentors’ frontman El Duce than anybody in their right mind would.

“A couple of times he passed out in the aisle of the drugstore after stealing mouthwash. They’d arrest him and then we’d have to bail him out for being drunk in Walgreens. You can’t tell me that’s not cool, man.”

S’pose not!

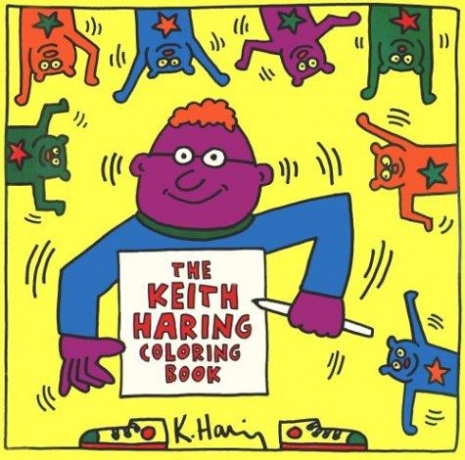

What does this man have in common with Al Jourgensen? It might not be the first thing that comes to mind…

More after the jump…