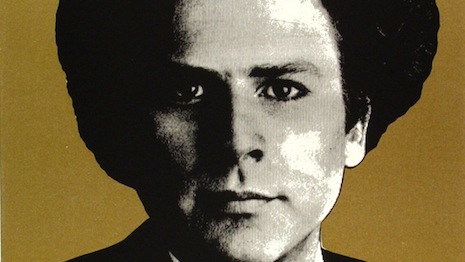

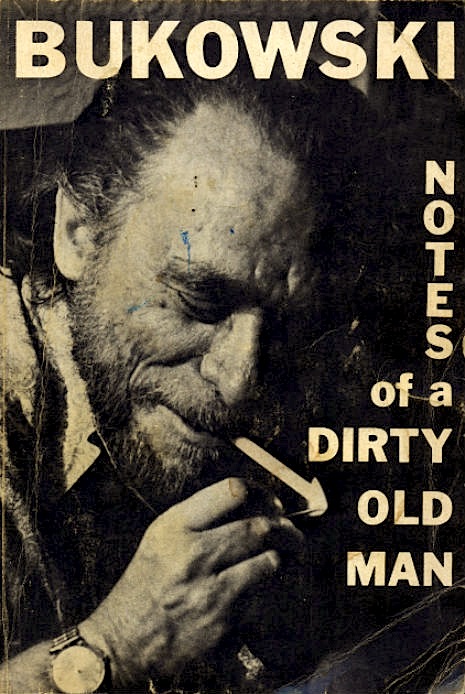

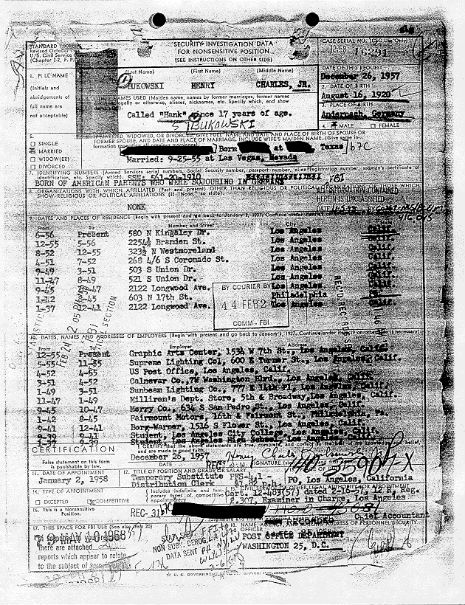

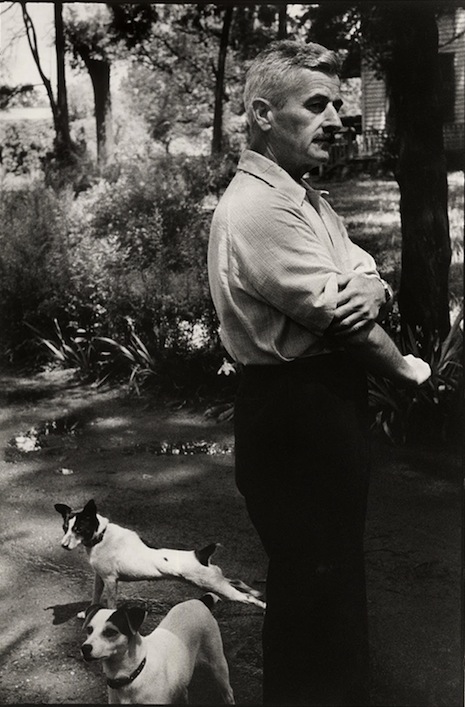

When William S. Burroughs’ novella “Ah Pook Is Here” was published in 1979, it was in a form greatly diminished from the authors’ original intent. That’s not a typo, because although it was Burroughs who wrote the text that was published, there were two creators of the far more elaborate work that it was cleaved from, Burroughs and Malcolm McNeill, a then 23-year-old illustrator.

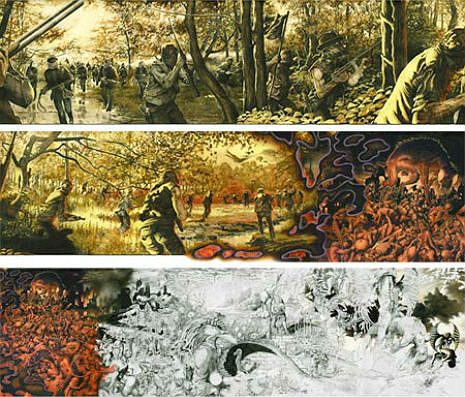

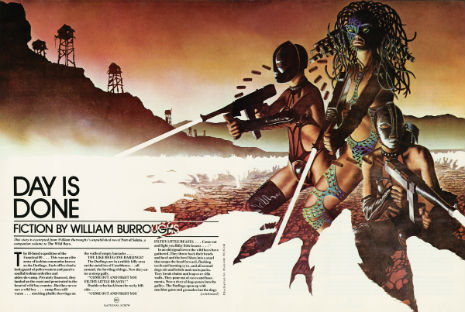

Burroughs’ apocalyptic text tells the story of a megalomaniac bastard (an “Ugly American” based on a powerful media tycoon like William Randolph Hearst or Henry Luce) who acquires the powers of the Mayan death god, Ah Puch. Conceived as “continuous panorama,” with accordion-style, linked pages in the pictographic format of the surviving Mayan codices—“an early comic book” as per Burroughs—the project, seven years in the making, consisted of over 100 detailed illustrations by McNeill, 30 in full color, and about 50 pages of text. “Ah Puch is Here” (as it was originally titled) would have been prohibitively expensive to publish at the time, but it was also rather racy and sexually explicit—including male on male imagery—meaning the pool of potential publishers was certainly very, very small to begin with.

As Burroughs wrote in the forward to the 1979 book:

“[O]ver the years of our collaboration Malcolm McNeill produced more than a hundred pages of artwork. However, owing partly to the expense of full color reproduction, and because the book falls into neither the category of the conventional illustrated book, nor that of a comix publication, there have been difficulties with the arrangements for the complete work. The book is in fact unique…”

That it was. “Ah Puch is Here” wouldn’t have been the first graphic novel—Burroughs’ own American publisher Grove Press had already put out Guy Peellaert and Pierre Barther’s Adventures of Jodelle as well as Massins’ graphic interpretation of Ionesco’s The Bald Soprano... There was Jean-Claude Forest’s Barbarella, Michael O’Donoghue’s The Adventures of Phoebe Zeit-Geist, Guido Crepax’s “Valentina” series, The Adventures of Tintin, lots of stuff comes to mind, but in the main these books were collections of episodic comic strips, not “serious” narratives originally conceived of to fit between two book covers or that would have required luxurious glossy printing to properly display the highly detailed Hieronymous Bosch-inspired photorealistic artwork within… Unique yes, then as now.

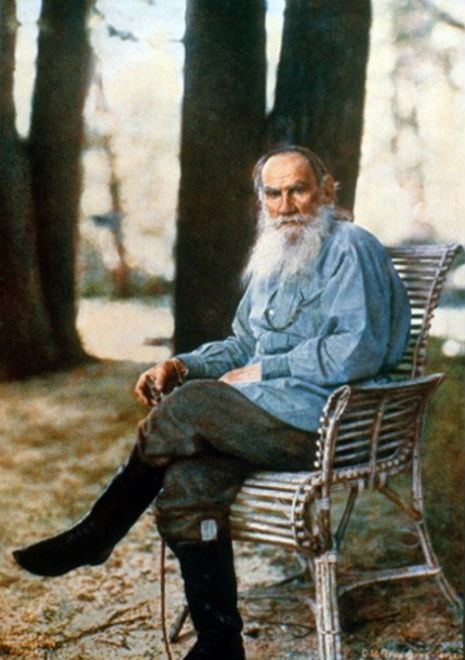

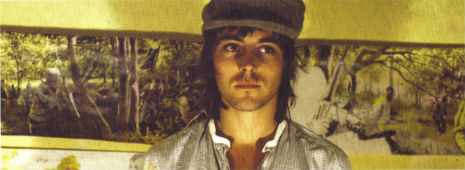

Burroughs collaboration with McNeill began in 1970, when the author was living in London and McNeill was an art student. Without any communication between them, McNeil illustrated Burroughs’ submissions to Cyclops magazine, “The Unspeakable Mr. Hart” and impressed him enough so that he wanted to meet the young artist. (It’s worth noting that McNeil scarcely had any idea who Burroughs was at the time, even so, he drew Mr. Hart, the villain, to look a lot like a younger version of El Hombre Invisible.)

After a year of museum research and preliminary design on a mockup, Rolling Stone’s Straight Arrow Books imprint agreed to publish the “Ah Puch” book and McNeil moved to San Francisco to work on it. Straight Arrow was shuttered in 1974 and eventually the project was abandoned before the text portion alone saw the light of day in Ah Pook Is Here and Other Texts in 1979. Malcolm McNeil went on to a distinguished career as an illustrator for the likes of National Lampoon, Marvel Comics and The New York Times and a motion graphics designer and director for film, advertising and television, including winning an Emmy for his work for Saturday Night Live. (This will be of interest to no one save for fellow vets of the 1980s New York advertising world, but McNeil’s Paintbox work was synonymous with Charlex, the NYC-based video production house probably best known for The Cars’ “You Might Think” video, dozens of TV show openings and hundreds of commercials.)

After some 30 years in storage, the by now fragile “Ah Puck is Here” artwork was restored by Malcolm McNeill for exhibition, and was shown at Track 16 Gallery in Santa Monica, CA, the Saloman Arts Gallery in Manhattan and elsewhere.

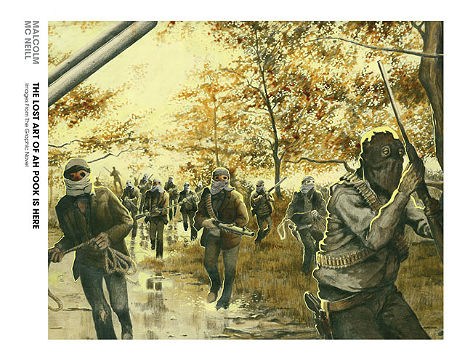

Fantagraphics have published two separate Ah Pook books, one a gorgeous coffee table book of McNeil’s extraordinary panoramic illustrations for the Burroughs collaboration, The Lost Art of Ah Pook Is Here: Images from the Graphic Novel and a memoir, Observed While Falling: Bill Burroughs, Ah Pook, and Me

, an intimate, affectionate portrait of their unlikely friendship and multi-year/multi-continent joint project.

The first book has very little text, and although it’s impossible to make heads or tails out of what is going on with the drawings alone, trust me, you get a very good sense of the epicness of the vision and also see some of what would have made 99% of the publishers of the 1970s very squeamish. Sadly, for reasons McNeil politely declines to go too far in-depth about, he was denied the use of Burroughs’ text for the Fantagraphics publication by his estate and this is a real shame.

However, if you have a copy of truncated 1979 Ah Pook Is Here (I do) it becomes an even more satisfying excuse to dive in deeply on the detective work and match passages from the text to the artwork. If you’re interested enough to purchase the coffee table book, surely you are going to have to rush over to eBay or ABEBooks and get yourself a copy of Ah Pook Is Here and Other Texts

, just bear that in mind.

Observed While Falling: Bill Burroughs, Ah Pook, and Me, the memoir and the third book in this trilogy, is no less essential for anyone seeking a deeper understanding of what made Burroughs tick, and should, along with the artwork that was regretfully parted from WSB’s text, be seen as one of the most exciting things to come along in Burroughs scholarship in recent years. It is, by far, the most observational—and highly personal/subjective, which makes it fun—look at Burroughs produced by any of his friends or collaborators. McNeil is a fine writer—the man must be a superb raconteur—and he never forgets who the book is really about.

I must say, as a longtime William Burroughs fanatic, I was wowed by McNeil’s twinned Fantagraphics books (which are beautiful matching objects) and spellbound by his tales of working with Burroughs. There are really three books here that you need, so it’s not a cheap proposition to acquire the lot, but if you’re a big Burroughs fanboy, it’s certainly well worth the expense.

Furthermore, if you’re so inclined Malcolm McNeil is selling very reasonably priced limited edition prints of several of his incredible “Ah Pook” panels.

The Dead City Radio recording of Burroughs reading “Ah Puck is Here” provides the soundtrack to this amazing short animated film directed by Philip Hunt with music by John Cale.