The ongoing series of Sherwood at the Controls releases surveys the recording career of Adrian Sherwood, the visionary dub producer and founder of On-U Sound. Volume One, released last year, covers 1979 to 1984, while the brand-new Volume Two takes us from 1985 to 1990.

As these discs demonstrate, Sherwood’s talents were too great to be contained by any genre. During the decade-long period under examination, his work connects everyone from Prince Far I, Lee “Scratch” Perry, and the Slits to Depeche Mode, Nine Inch Nails, and Ministry. (“Al [Jourgensen] would go to the toilet and copy down the studio settings Adrian used for his effects on toilet paper and put them in his trousers,” Revolting Cock Luc Van Acker remembers from the Twitch sessions.) As I mention below, I think On-U must be the only point at which the discographies of Sugar Hill and Crass Records intersect. These comps also contain a sampling of the pathbreaking records Sherwood made with On-U outfits African Head Charge, Tackhead, and Dub Syndicate, which redefined what dub was and could be.

I spoke to Sherwood on June 24, the day after the United Kingdom voted to leave the European Union.

Dangerous Minds: I spent yesterday listening to Don’t Call Us Immigrants as I was watching the Brexit votes come in—

Adrian Sherwood: [laughs]

—I feel I have to ask you about that. What are your thoughts?

Well, we would like to have stayed. There’s lots of reasons I would stay in Europe, and I’m sad, really. Europe’s done a lot, really, for each other. Apart from keeping a lot of peace and stability, the farming lobby in France and the farming lobby in Italy’s very strong, Germany’s got the biggest Green Party membership in Europe, they’re very advanced in renewable energy, and the farming lobby makes sure that we’re not victim of any of the terrible things that happen in the States with the poisoning of the food chain. So they’re very, very good; they ensure the standard of organic food, et cetera et cetera, and they also fight for workers’ rights. So I could go on and on about it, but I firmly would have liked to have seen a strong EU that we were part of.

You know, if they’re worried about immigration, they could have a united policy, but it was all panic, panic, panic, and to be honest with you, it was more like the ignorant masses that wanted to get out, thinking “Oh, let’s stop immigration,” but there’s no such thing as an indigenous English person. Every last person in this country is of an immigrant extraction. Everybody.

Lee Perry and Adrian Sherwood, photographed by Kishi Yamamoto

I wonder if I could go back to the beginning of your career. What was the relationship like between the Jamaican roots artists and the UK scene? It seems like you were in a special position to observe their interaction. Was that a competitive relationship?

No, not in the least. It was very hard for the English artists to get credibility, because everybody was looking to Jamaica, as though there’s the great thing, like the British bands always looking to the great American bands. The situation was always the exciting new star coming from Jamaica, and everybody really wanted to see him or her—mainly males, but a lot of female artists as well—and people didn’t think they could get the sound. So it took quite a long time for the English… you know, that album Don’t Call Us Immigrants, it’s interesting that you mention that, ‘cause I’m proud of that album. But that reflected the development of the English reggae sound.

We developed a sound of our own in England, with bands like Steel Pulse and Aswad and Creation Rebel, et cetera, and, you know, Black Slate, Dennis Bovell, obviously, and then eventually the lovers rock scene and our own dub scene. But Jamaica led the way, so everybody in England was like “Oh wow, here’s the new hip hero coming from Jamaica.” It wasn’t really like competing as such, it was more “Bring on the new star,” really, and everyone in England was keen to see the new star. And a few of the really good bands in England got to back the stars, like Aswad did one of the most famous ever gigs backing a young Burning Spear in ‘76 or ‘77 or something.

Since you mentioned Creation Rebel, can you tell me a bit about Prince Far I? I’ve listened to a lot of Prince Far I but I have almost no sense of what he was like as a person.

Far I was a bit of a joker. He would stand on the table and do Elvis Presley impersonations. He had a very mad sense of humor. But his background was quite serious. He was friends with Claudie Massop who was a political gunman, and he himself had been like a security man at Joe Gibbs’ studio, the doorman. He’d worked on a bauxite factory, producing aluminum, where Claudie Massop was the foreman, and because of the politics, he was like a “big friend,” as Joe Higgs said, like a big friend to Far I. But Far I was a character, quite a complex character as well. He looked much older and seemed much older than he actually was.

Did he seem like a wise person? Was that part of it?

Yeah, he definitely had a lot of depth to him, was interested in things and read quite a bit. But he was a joker and a character, and I remember him being full of jokes and fun and stuff. Although he had a darker side as well, which was more one of feeling that people were working voodoo on him, y’know, things like that. So there was kind of a strange underbelly there as well.

From the little I know, it seems like the reality was pretty heavy for a lot of those guys. Tapper Zukie was involved in some violence… it seems like that was just part of life for a lot of those guys.

Well, I knew Tapper Zukie from that period. My friend, Clem Bushay, he lives about 200 meters from me; he actually produced the Man Ah Warrior album.

No way.

Yeah, the producer lives on the same road as I’m speaking to you from now. I knew Tapper Zukie for a long time.

They were all affiliated with politics, that was the thing. And in the seventies, in Jamaica, obviously, the CIA were moving in, trying to destabilize the country, because they didn’t want them to slip towards the Cuban model and affiliate with Russia, and have another Russian ally so close to the United States. So a lot of arms were put in to Seaga, who was affiliated with the Americans, where Manley wanted to stay with the Cubans and work more to a socialist state. That’s why there’s so many arms and, to this day, so much trouble for Jamaica.

It was a crazy election—I think it was ‘76—and I was eighteen at the time, and Far I was with us in England. It was mad. Phoning home and, you know, ten, 20 people shot a day in the political violence. And Far I obviously was close with Claudie Massop, who was one of the main enforcers, like his father Jack Massop had been. But we met a lot of those gunmen: Take Life[?], Bucky Marshall, Tapper Zukie, Horsie—not Horsemouth Wallace, another one called Horsie. Were some quite dark characters, really, but if you met them, you’d have thought they were really charming. But then what they actually got up to was a whole different thing.

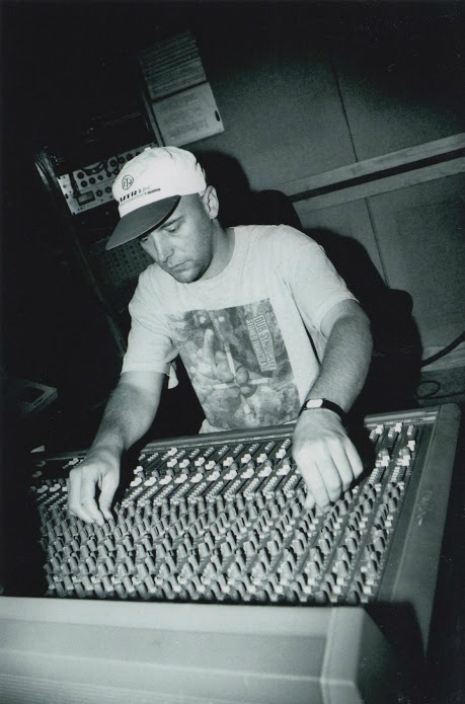

Adrian Sherwood and Style Scott, photographed by Kishi Yamamoto

Because there’s so much material, how did you decide what to include on these two volumes of Sherwood at the Controls?

I’ve got to be honest with you, I’m working with Warp Records, and I’ve got a few very good allies that I trust. I’ve got my friend Matthew doing these compilations, because I trust him, and he’s not gonna just do what I would do. So I’ve got my friend to actually put them together, and he felt it represented me not just from the reggae background, it’s showing a different angle. So we’re not really particularly dropping much of the reggae-flavored stuff at the moment, or the more hardcore reggae stuff. This is reflecting a different set of stuff that I worked on.

Well, it’s such an interesting group of people that you’ve worked with. I think probably you’re the only person whose career brings together the Sugarhill Gang and Crass Records. The compilations do a really good job of sampling that period without giving too much, you know, they’re concise.

Yeah, I’m pleased with them. If I’d done it, it would have been more of the same, so I’m very grateful to the people I’m working with. We’ve got a good little posse of friends and people around us, and Matthew’s selecting that series for me. Did you get the Trevor Jackson album as well?

No, I haven’t heard that one.

Trevor Jackson did a triple album called Science Fiction Dancehall Classics which is another set which is worth checking out as well. That came out this year as well.

This new disc covers 1985 to 1990. From a technical point of view, what was the biggest change in the studio over that period?

Well, for me, it wasn’t just the technical side—well, it was obviously technical as well, but we moved more from live recordings to using drum machines for the first time. From about ‘82, ‘83, we started using drum machines, whereas prior to that, up to ‘83, I’d never used a drum machine, it’d all been live musicians. So by the time I got to ‘84 and had met Keith LeBlanc and worked with Steve Beresford… Keith was great with a drum machine, although he’s a great kick drummer, he was also at that time getting really good at programming. So we then got more and more into the programming of drums.

And look at today: nowadays, if you look at the charts, probably 95 percent of the things on whatever chart you’re looking at—apart from country and western or something, or heavy metal—most stuff is programmed. At that time, it then suddenly was, okay, in comes the drum machine, in comes the programming. The engineer became much more important in some respects than the bass player. It was like the engineer’s time came. And me, getting my hands on the mixing desk from an early age and being wrapped up in the dub scene, or the reggae scene, and the heavier stuff as well, I just applied those techniques to everything that came my way. So it was quite fortuitous in that respect, really. I learned from the reggae thing, I could apply that to working with Skip, Doug, and Keith, or Crass, or Bjork, or any of the other things that we engineered.

One of the tracks on here is a Ministry track. I know that in Al Jourgensen’s book, he says that he learned everything he knows about production and mixing from you. Is that how you remember it?

Yeah, I remember Al very fondly, I miss not seeing him in all this time, really, that’s very kind of him to say. I like that.

He contacted me in ‘84, and I went over there in ‘85. He had just had his daughter and I had just had my daughter. He’d had his daughter who was called Adrienne, the American spelling which is a girl’s name, and I’d just had my daughter Denise; they were both the same age. I was in Chicago with the Wax Trax! people doing the early recording, then we went to Hansa Ton in Berlin where I’d been with Depeche Mode, and then I brought him to England to Southern, which was where Bjork, Crass, even Minor Threat and all that lot would all work in that studio. That was a very important studio, Southern. And we finished the Ministry record up in there. I’ve got very fond memories of Al, and sorry I’ve not seen him for so long, really.

Bonjo Iyabinghi Noah and Adrian Sherwood, photographed by Kishi Yamamoto

Since you mention Southern Studios, I read something that Youth from Killing Joke wrote about his early years playing in punk bands. He talks about playing on an Annie Anxiety record and he associates her with the “Adrian Sherwood, Crass posse.” Could you tell me about how you fell in with those people? Was that about working at Southern?

John Loder came looking for me. My then-partner Kishi Yamamoto, who is the mother of my two eldest kids, [and I] were running On-U, and we’d just started it, and he came to look for me and said “Look, I’ve got this studio, come and work in the studio.” I was working at Berry Street [Studio] at the time. So I spent a whole evening with John, and then said goodbye to him and called him something else—I couldn’t even remember his name at the end of the evening [laughs]. I was in a bit of an, um, not the most healthy mental state at the time, I suppose, being a bit stoned or whatever. And I ended up going to check his studio out and loving it.

John Loder was actually an amazing, amazing engineer. But he became in love with the business more than with the music. He engineered all the early Crass stuff, and he did loads of amazing American and English punk, new wave guitar bands, whatever you want to call them. But John also was the first person to invest massive amounts of money in a computer that I ever met, and he was completely into that, and I think he was into Scientology. He was a very unusual fella. But I did like John a lot, and he held together a most unusual place, because he had his two buildings next to each other, two three-story houses. He lived in one, and on the top floor he could walk from his office into his own house where he’d knocked the wall down from one building to another. Underneath that was the whole Southern organization, and on the ground floor was the live area and the kitchen where all the musicians—you know, we’d hang out there, seriously, with KUKL, (who became the Sugarcubes and then became Bjork), Lee Perry, Bim Sherman, African Head Charge, with Crass, with the Exploited, with the Subhumans, with Big Black, like I said, Ian, Minor Threat, the Washington lot—it was a mad place, and you’d queue up to get in the studio. And I usually did midnight ‘til nine in the morning, that was my stint. And that was where we cut the first Tackhead things as well.

African Head Charge is a special thing. How were those records received at the time? They still sound futuristic to me.

Oh, thank you. Well, the thing was, it wasn’t a band; it was really an idea my wife and I had, Kishi and me. We were trying to just experiment in the studio, and it started at Berry Street before we met Loder. I’d worked with Bonjo in Creation Rebel, and he was versed in Afro-Cuban beats as well as Nyabinghi and the other things, so we decided to make a record [that was] very percussive, and make a kind of psychedelic African dub record. So the first four albums are really very experimental, and it wasn’t until you got to the fifth album that it became a little bit more focused and we started doing it live, and it eventually evolved into a kind of live band. But like Creation Rebel and Singers & Players, they were all studio projects before they ever did a live gig.

Did the change in technology that you were talking about with drum programming have an effect on this collective of musicians that was around?

I think it had an effect on musicians all around the world, because obviously people weren’t needed quite so much. Some engineers would be programming drums, programming the bass, and programming the sequencers, and a lot of musicians were hungry; they couldn’t get the work they had before. I mean with those records, all those early Head Charge albums, they weren’t programmed at all. They were all played. Every African Head Charge record up to Shashamane Land, the first seven albums, were all totally live. One or two tracks were totally made out of tape manipulation, a few of the tunes, but there was no programming or anything. It was tape manipulation on some tracks or live playing.

Was Tackhead more of an outlet for sampling and programming?

Well, Tackhead started where, firstly Keith LeBlanc came to England, then he had a little look in, and then he brought over Doug and Skip. And we started out doing some shows with Mark Stewart just to get them over, and the first thing we did was called Fats Comet. I said, “Look, I’ve been running my own label since I was seventeen,” which Keith found very hard to believe, and then we all got together and said “Why don’t the four of us start our own label?” Which was World Records, which we did through John Loder. So we put a couple of twelve-inches out on On-U, then a few records out on the World Records label, and it was the first time I think that they’d actually owned, had any stock in, their own work. ‘Cause they’d all been working at like Sugarhill, getting paid and owning nothing, and suddenly here they were in London, filling out venues, meeting a lot of crazy people in London at the time, and it worked for all of us. It was really, really good fun. We had a five-year period where Tackhead was smashing the place up, really.

Adrian Sherwood and Ari Up

Do you have any memories of working on that Vivien Goldman Dirty Washing EP? I love that record.

Yeah. Viv was a journalist living in Ladbroke Grove, and she was mates with everybody. Viv knew everyone. She was friends with John Lydon, she was mates with the Clash, with Niney the Observer. Vivien would ingratiate herself with people, she was very friendly, and she decided to make a couple of tunes. So I helped mix a couple of free tunes for her. But she’d got in, I think, members of Public Image were playing on those tunes, you know?

Right, what I’ve heard about it is that when they were recording Flowers of Romance they gave her some studio time.

Yes, that’s true. Well, that’s when I met them all as well, in that period. I knew John Lydon because Ari Up’s mum was his girlfriend.

Nora.

Nora, they were boyfriend/girlfriend at the time. And I was squatting just ‘round the corner, and he’d come and visit us and he’d invite us ‘round to the house, ‘cause he had a video player—nobody had a video player in those days. I actually really liked John Lydon, but I haven’t seen him in donkey’s years. But he’s a good bloke. He introduced me to Keith Levene. Keith had a bad heroin problem, which is sad, ‘cause it unfortunately scarred his life, as far as I’m concerned—it’s no fun spending your life as a junkie, it’s really sad. But he was marvelous, lots of ideas and a really good musician. So I think you’ve got Keith playing on those tunes, you’ve got a fellow called Shooz, who was a drummer, and a couple of characters who were around, Martin Atkins or whoever. And Viv was my friend, and she liked Starship Africa, the album I’d done, and she said, “Will you come and mix it?” I said, “Of course.” So I went and mixed them all in about… two hours each tune, or something. I did them all quite quickly.

Yesterday, when I wasn’t busy worrying about the British vote, I was worrying about Sinead O’Connor, who I know has said that you saved her life once. What’s your relationship with Sinead O’Connor like?

Well, I haven’t seen Sinead for a few years, but if we saw each other now it’d be very, very close friends, y’know, it’d be no problem whatsoever. I did a couple of records with her, and I really respect her, she’s a great artist. Her eldest son Jake, he’s friends with my eldest daughter. We don’t see each other, that lot, but if we were together we’d have a very nice time and be very glad to see each other. If you’re mentioning friendship, or artistically, on both levels, I think she’s a great artist. Is that a good answer? [laughs]

Yeah, I just admire her courage. And she got a raw deal, especially here in the United States.

Yeah, but you know, sometimes, if you speak the truth—I mean, she was speaking out about the hypocrisy and the child abuse in the Roman Catholic Church, and the abuse of young women by the nuns—you know, the what’s-her-name sect of nuns where she was in one of the schools. She was shouting from the rooftops, “Fuck the Catholic Church,” on TV in America, “these people are pedophilic child abusers,” and she was vindicated.

That’s right. It took a while, but when she was saying that, nobody else was saying that.

No. It’s the same as when John Lydon was going on saying Jimmy Savile’s a pedophile, as well. People didn’t think—they kinda hushed up what he said.

What are you working on now?

At the moment, I’ve just released an album with Nisennenmondai on On-U. I’ve got a new Sherwood and Pinch album nearly finished, and I’ve got a couple other albums ready to be released, but I’m trying to make sure the ground is set so I can promote them, because the worst thing is putting out a record and nobody knows it’s out. I’ve got another album called Dub No Frontiers which is a wonderful album, and the next release will be Sherwood and Pinch, second album.

I saw you at Dub Club in LA a couple years ago, that was great.

Yeah, that was fun. Did you enjoy the night?

Very much. Do you plan to tour any time soon?

The problem for me is my age and my health. I don’t wanna be battering myself playing, you know, Tuesday night to like 50 people in some weird backwater in America, you know what I mean? [laughs] I’d rather stay here. But if somebody says to me, “Look, there’s a festival, come and do a live dub show with all the equipment,” I’d love to. I actually did it in LA with a bit of the equipment for once, ‘cause it’s hard lugging stuff over. I enjoyed that weekend. So I would like to come back again.

Sherwood at the Controls, Volume Two is now available from On-U Sound and Amazon. Below, listen to the second track on the compilation, Tackhead’s “Mind at the End of the Tether.”

The trailer for Sherwood at the Controls, Volume Two: