Earlier this year, at the opening ceremony for the fifth session of the Scottish Parliament, makar or national bard Jackie Kay read from her poem “Threshold.” The poem is a rallying call for people to come together and protect the nation’s “incipient democracy”:

Find here what you are looking for:

Democracy, in its infancy: guard her

Like you would a small daughter -

And keep the door wide open, not just ajar…

Though I don’t regard Scotland as nation with an infant democracy—our history tells us otherwise—it is fair to say the poem’s sentiment is well-intentioned—if a tad cutesy. Democracy must be guarded responsibly if we are to enjoy its freedoms.

The issues of freedom and democracy are at the heart of a new feature-length documentary by writer and director Rupert Russell. His film Freedom for the Wolf is epic in scale—covering events on four continents—finely made, thoughtful and nuanced. It examines how different people across the world—from Tunisian rappers to Indian comedians, from America’s #BlackLivesMatter activists to Hong Kong’s students—are joining the struggle for “the world’s most radical idea—freedom—and how it is transforming the world.”

This sounds all very exciting—though I don’t think the struggle for freedom as something new—it has been a central thread of human history for millennia. Yet every generation comes afresh to politics (most recently the Occupy Movement and Bernie Sanders revolution) and sex (Fifty Shades of Grey)—and so it is with Freedom for the Wolf.

That said, Russell’s film does highlight how different movements, primarily youth movements, are fighting the threat of governments combining dictatorships with democracy to create what is termed “illiberal democracies.” In other words, countries replacing real democratic freedom with consumerist choice—the right to liberty exchanged for the right to shop—or, as Juvenal put it, “bread and circuses.”

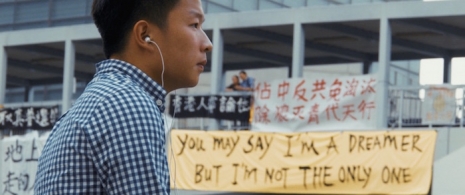

Occupy demonstrator in Hong Kong.

Rupert Russell was born and raised in England. He is the son of the brilliant film director Ken Russell. Rupert graduated from Cambridge University before he went on to study for a PhD in sociology under Orlando Patterson at Harvard University.

Patterson is a preeminent historical and cultural sociologist—best known for his work Freedom in the Making of Western Culture (1991), which won a National Book Award. Born in Jamaica, Patterson has long had an interest in the cultural meaning of freedom. His interest was inspired by his birth country’s association with slavery. Slavery has shaped our understanding of freedom. Patterson examined slavery from a long historical perspective pointing out that the derivation of the word slave comes from the ethnic group Slavs. Blond, blue-eyed Slavs were once the main ethnicity of slaves—further the “vast majority of slaves for over 2,000 years of Western history were white.” But it’s a different kind of slavery that threatens democracy today.

Patterson appears in Russell’s documentary and his work on freedom—what is it? what does it mean? how is it being eroded today?—underpin some of the film’s central themes—as Russell explained to me when I spoke with him over the phone:

Rupert Russell: Our original intention was to examine what freedom meant in different cultures around the world. I’d been thinking about freedom and the paradox of freedom for quite a while and I decided to do a bit of exploration into not only what freedom means in different cultures but how does it relate to power.

My advisor at Harvard during my PhD was Orlando Patterson who had already done quite extensive research on this. For example, he examined how ordinary Americans when you ask them to talk about “freedom” there were all kinds of things they said from being naked on a beach to driving their car. But invariably what they they didn’t talk about was voting.

Orlando’s hypothesis actually explains how people such as George Bush and other politicians of the Iraq war era were able to use the idea of freedom in the forefront of their rhetoric while at the same time eroding democratic institutions through things like the Patriot Act.

I was already aware there was a very sophisticated way to think about the relationship between freedom and power—the different definitions of freedom and how they can interplay with each other. How we may emphasise in a culture too much of a personal version of freedom and not connect that with a democratic or institutional version of freedom upon which our personal freedom depends.

****

The title for Russell’s film Freedom for the Wolf comes from a quote by philosopher Isaiah Berlin:

Freedom for the wolves has often meant death to the sheep.

That’s the films opening pitch, before it moves onto the substance of the recent Occupy Central and Umbrella democracy demonstrations in Hong Kong in 2014.

The film opens with a group of demonstrators protesting China’s new electoral reforms by having their heads shaved. The demonstrators want free universal suffrage, free elections and the right to have a democracy. They believe the new reforms being ushered in by the Chinese government for 2017 will remove Hong Kong’s autonomy, and force its citizens to accept state sponsored politicians selected by the government in Beijing.

The issue stems from the fact Hong Kong was under British rule for some considerable time. This inculcated a sense of democracy and freedom then unimaginable in the rest of China.

In 1997, Hong Kong was given back to China. At the time, it was agreed Hong Kong would be ruled under the “one country, two systems” rule devised by Deng Xiaoping. This allowed Hong Kong and Macau to retain their capitalist economy, while the rest of China would still be governed by a socialist system. Now this is changing—which led to the Umbrella protests.

The story of these young radical students provides an in to the film’s thesis on the rise in illiberal democracy.

****

Dangerous Minds: How did you manage to film the Umbrella/Occupy Central protests in Hong Kong?

Rupert Russell: We actually just got really lucky is the simple answer to that. We actually did Japan and Hong Kong as part of the same trip. We knew the protests were coming. They had been threatening to do this civil disobedience action for a long time. We went early September right around the mid-autumn festival they have there. It was all starting to kick off. We thought, This is an interesting story—a democracy struggle in Hong Kong

What’s interesting about the Hong Kong case study—is that China’s basically trying to do is to set up an illiberal democracy by design. With almost all of the other countries we examine it is almost something they are stumbling upon. It doesn’t matter whether you are Saddam Hussein or Assad—you kind of need to have this ritual of election. That has become a norm in our political culture. What these autocrats have discovered independently of each other is that elections need not be a challenge to the existing power structure of any regime necessarily.

China kind of figured out that what they could do was set-up an illiberal democracy by design. Meaning they could take the main institutions of a liberal democracy—such as freedom of association, freedom of the press, be independent of the judiciary, even independent of political parties, and have the ability to field candidates. They could take each one of those institutions and systematically undermine them.

You saw this particularly with the press which has been going on for years. The Hong Kong press has been very critical of the Beijing authorities representative in Hong Kong. You have seen an extremely systematic campaign to close down this pocket of free expression within China. They don’t do it through illegal means—they don’t come in and say “We’re going to close you down.” They do it more indirectly.

For example, there was a big story in the New York Times around this time two years ago about how the China liaison officer had gone to the world’s major financial institutions—such as HSBC and Standard Charter—and said, “You’ve got to stop taking out advertisements in certain publications.” I mean they were really talking about the tabloid paper that was very pro-democracy called Apple Daily. They did. They pulled out $20 million worth of advertising from the paper in an effort to bankrupt it. That sends a signal to the other newspapers if they were critical of Beijing then there would be repercussions.

Director Rupert Russell during the filming of ‘Freedom for the Wolf.’

DM: Has there ever been a history of freedom and democracy in China and Japan?

Russell: What I found very interesting when we first started filming was—we mention this in the film—is that the Chinese and Japanese language did not even have any words for “freedom” until they came in contact with the West. Even when they did have the word “freedom” their translators tended to pick words that meant “selfishness.”

So when we first went to Japan, what struck us straightaway was that people’s ideas of freedoms were very similar to people’s ideas in the West. The same sort of ideas you would get in Orlando’s research. This kept on happening in every country we went to—people talked about freedom of speech, being able to say what you want, do what you want, and if they went further than that they would talk about democratic rights and so forth.

What we actually found was that people’s ideas of freedom were very similar.

DM: Was there any reason why this should be?

Russell: The reason why this was happening—as we found out was when we started filming—was that there was this other trend of illiberal democracy.

Why do cultures have similar ideas of freedom? Well, most of the ones we were looking at were democracies or in a democratic transition and the kinds of democracies that were emerging all had similar features to them. People’s ideas of freedom were a reaction to the political context they were in.

Initially we thought people’s ideas of freedom all over the world would be disconnected from one another. What we found was because we are undergoing this wave of illiberal democracy throughout the world people’s ideas of freedom were actually homogenized. Because people whether you were in Tunisia or in Hong Kong or in the United States or maybe the UK people are undergoing the same problems with the police, the same problems with elections, a clampdown on freedom of speech and surveillance.

These were very very common themes that we were seeing everywhere. We just saw in London this week photographs of the Met officers in militarized police gear. And while you can talk about each country individually—why is Tunisia illiberal? Or why is India illiberal? Or why is Britain becoming more illiberal? You can tell a different story for each one of those countries which relates to a specific context.

I think what is a fascinating and perhaps unanswered question is why is all this happening now?

Why is each of these countries moving towards an illiberal democracy? Is it a coincidence? Is there something deeper driving it? Is it a response to immigration? Is it caused by economic uncertainty?

Is America losing its liberty?

DM: Wasn’t there a belief in the West that economic liberalization would ultimately lead to political democracy?

Russell: There was that old way of thinking about this—the kind of Washington consensus that with economic liberalization is going to come political liberalization. So through free trade, capitalism, growth, your population is going to start demanding political rights as well. I think now that model which was really big in the nineties is now really falling into question because people can see [Russia’s President] Putin have really high approval numbers without any political liberalization at all.

The key question that is raised in this film is—“Okay, fine. When oil prices are high or when the economy is growing it looks like that kind of social contract would probably work. But what’s going to happen when you have a downturn which China has had now?” You can even see in things like the accusations of stock market manipulation like when the Chinese stock market plunged last year—all kinds of journalists were rounded-up and forced to give confessions about how they had spread false rumors about the stock market in an effort to undermine the government.

You really can see this tension between the benefits of free market and the capitalist system and the certainty of an authoritarian system that wants constant growth. You can see the confessions of these journalists as examples of that kind of tension.

The question you’re going to see over the next ten-twenty years is this model, the China model, the Kuwait model, the Gulf model of growth without rights going to work in the long term.

The rise of religious intolerance in India.

****

Russell’s film then moves focus to Tunisia where the much vaunted hopes for democracy stemming from the Arab Spring look like they have come to nought. Unsurprising considering the country was a former dictatorship and police state which is now under the influence of the Muslim Brotherhood.

****

Russell: I think there’s a tendency in the West to hold up Tunisia and India in particular as kind of bastions of successful democracies in Western society. I think the West’s desire to do this biases us in observing what is actually going on on the ground. We just want to say it’s a success story and move on.

Tunisia is definitely on the way to illiberal democracy. A bit like Egypt. It’s a very fast moving situation and it depends on the personalities that are in power at the time rather than any kind of longterm institutional changes. Our story that we did was really about these personalities who we were fortunate enough to get on camera. You have the President of the country Moncef Marzouki—a long term human rights activist who has been a longterm opponent of the previous dictatorship. Then you have the coalition called the troika with the Islamist Party Ennahda.

Unlike Egypt which was a military dictatorship, Tunisia was a police state—pretty much one of the strongest police states in the region. As Marzouki said in our film, he wasn’t able—it wasn’t practical—to disband the police like the Americans had done in Iraq when they disbanded the Iraqi army—probably one of the biggest blunders in American policy in the last hundred years. Unfortunately what you’re left with is a police force which has been trained under the old regime which still unfortunately engages with torture which is all too willing to clamp down on people who criticise the police and criticise public figures.

****

Among the interviewees is a rapper who has been in out of jail for expressing his views about the government. The fact he is a rapper in an Islamic country brings out an unacknowledged theme in Russell’s film—the much valued ideals of democratic freedom have more to do with the West than with religious police states or communist countries.

In America Russell interviews a woman working for the Republican party who explains how money has made politics a past time for the rich. This woman once worked with small business companies to raise money for their senators so their voice could be heard in government. Now, billionaires bankroll the politicians—so the public no longer have access to their elected officials—which raises the question.

****

DM: Has there ever been a full and fair liberal democracy?

Russell: I think there has. I think the way to think about these things is not to think in absolute terms but in relative terms.

What we ask is not whether Britain or America is a liberal democracy but are they moving in a more illiberal direction?

That’s how I would phrase it.

As much as we are critical of the United States in our film there most definitely is—in the complicated ways our government is able to pressure major news organizations (those things are quite complicated and well documented)—there is pretty incredible press freedom still in the United States. I don’t think we should take that for granted. I think in western Europe and the United States these liberal institutions are definitely being eroded. I don’t think there’s that much debate about it. But still when you start comparing them to other countries such as China, Russia or even India right now, you can begin to see the stark difference.

On whether I think we are moving in a more liberal direction or a more illiberal direction—I would say in the last fifteen years or so we’ve definitely seen us move in a more illiberal direction.

One question you can ask is really around growth which we come back to in our film: Is liberalism and our basic conception of life dependent on economic growth? When you don’t have economic growth do people become more populist? Do they become more authoritarian? Is there a move towards that? Perhaps that’s what you’ve been seeing over the past fifteen years. You know, you’ve been seeing declining growth and wages, and a kind of dissatisfaction from the status quo. It’s been very easy for politicians to turn on these liberal institutions and point the finger at them—“This is undermining order, this is undermining growth, undermining stability.”

I think we definitely see it in waves. I think the United States is so full of contradictions—the obvious being between some parts of the population enjoying a free ride—whether that’s the right to free speech or the right to own firearms. On the other hand you have this prison-industrial complex being established at the same time.

When you’re looking for freedom you ask freedom for who in this society? It’s usually not that there is more or less freedom in society but it’s usually some people are getting all of the freedom and some people are getting none of it.

****

Rupert Russell has made a highly original and thought-provoking film. It examines the dangerous rise in illiberal democracies which is not just happening in China or Tunisia or India but here in the West in the ‘home of the free and the brave.’

Freedom for the Wolf will be released next year.