Of the so-called Krautrock bands, Harmonia’s music is the most beautiful. It often sounds as if they’re playing colored lights rather than musical instruments. As Julian Cope writes of Harmonia’s first album in Krautrocksampler:

Each piece was a short vignette of sound which faded in, filled the room with its unearthly beauty, then left just as quickly.

Formed in 1973 by guitarist Michael Rother, who had founded NEU! after leaving Kraftwerk, and electronic musicians Dieter Moebius and Hans-Joachim Roedelius, who played together as the duo Cluster, Harmonia lived and recorded in a communal setting in the rural town of Forst, where Rother still lives. Brian Eno, who believed Harmonia was “the world’s most important rock band,” traveled to Forst to record with the trio in 1976, after the group had already agreed to break up; he described what he found there as “a small anarchic state.”

Harmonia only released two albums during their brief career, both essential: Musik von Harmonia and Deluxe. Tracks and Traces, the album resulting from Harmonia’s collaboration with Eno, did not come out until 1997; a decade later, the release of Live 1974 brought the total number of Harmonia records to a slim but sturdy four. On October 23, Grönland Records will release Harmonia’s Complete Works, a five-LP box set that supplements all of the above with a new archival release, Documents 1975, plus a poster, a pop-up, and a booklet with photos from Forst and an enlightening essay by Geeta Dayal.

I spoke with Michael Rother about Harmonia’s remarkable career early one morning in September.

It strikes me that you have a really distinctive guitar tone. I feel like if someone was playing a recording of yours that I’d never heard before, I could identify that it was you. Do you have any insight into how your tone developed?

Of course, this is a compliment. Actually, it should make me happy. It makes me happy—and maybe it’s also true, to a certain degree—but there is no real secret about the guitar. I think it has to do with the way I play guitar.

I used to, in the sixties, when I was still a copyist, a copy guitar player, copying heroes like Harrison, Clapton, Hendrix, Page, and whatever [laughs], I tried to play the rock’n’roll, rock type of guitar. But I stopped that in the late sixties, and the idea was to throw away the fast fingers and concentrate on one note, and then gradually find out what I can express on the guitar without being a copy of someone else.

And, of course, maybe you’re right, the fuzztone is special. I have a fuzz—the original was built for me in the seventies, but not NEU! so, see, it can’t be the only explanation—that was built when I was with Harmonia, by some people in the vicinity, music fans and also musicians. And this guy built a copy of, I think it was a copy of a Big Muff or something like that for me. In recent years, I was lucky that a real audio guru, a real, very talented, experienced studio electrician—electrician, maybe not; like, he knows all about studio technology, and he can build stuff—so I asked him to rebuild that fuzz, and to build it in a slightly smaller case, so that I can carry it around the world. And he laughed when he looked at the original copy from the seventies, and said “Ha, ha! These people have made a mistake!” And I asked him to stick to that mistake, because maybe the mistake is partly responsible for the special sound.

But I think—that is probably one aspect, but the idea behind the guitar playing, how I build up several guitars in one track, I think that’s also a very important factor, creating some individual sound. When I started with NEU! I remember I had this vision of making my guitar sound like an oboe, you know, the wind instrument? Like, fading in? So I had these two volume pedals, and if you listen to tracks like “Neuschnee,” for instance, you hear an example. And by EQing the guitar, and then also, of course, adding delays, et cetera. But the idea of a guitar not sounding like a guitar was something that was, from the beginning, in my head. It was supposed to sound different.

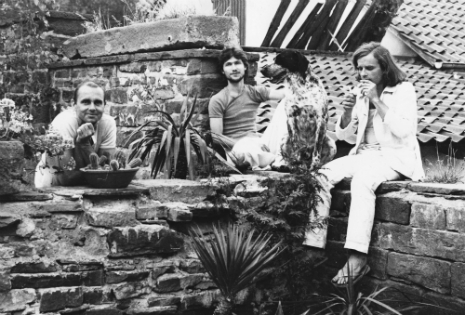

I have to admit that I always pictured Harmonia’s music coming out of the city, in more of a laboratory setting, so I was really surprised to see in the booklet that comes with the box set that it was more of a communal situation with dogs and families… there’s one picture of a guy named Jerry Kilian lying on a couch with a beer bottle underneath. What can you tell me about life at Forst?

That’s an interesting thing, what you say about how you imagine the music to come from the city, because sometimes people say the opposite, and they ask me questions like, “Do you think the music by Harmonia could have been the same if you had, for instance, lived in Berlin, and recorded music in an underground studio without fresh air, without any windows?” Of course, it’s hypothetical; I have no real explanation. But what I try to say to those questions is: I believe that Roedelius, Moebius and I already had some kind of vision for the music which would have been independent of the place where the music is played. But, of course, partly the wonder for this magical place—because it’s not only the communal aspect, it’s also looking out of the window and seeing a river and fields, no human structure in sight, and to have this kind of open space—at least, it was something that appealed to me straight from the beginning, this feeling of being at home, sort of, hasn’t left me since.

You know, I still live here. My studio was the Harmonia studio, where you see the three work spaces of Roedelius, Moebius and mine—I think it’s also in the book—you see the gear set up. That room is still my studio. Of course, it has changed; the gear has changed, and recently, since the arrival of the computer, that has significantly changed again, because I can work, I don’t know, I can work in a closet! [Laughs] All I need is a computer and a guitar, like I work live, you know. That setup which I carry around the world is what I basically need, and of course if I have some more gear, that’s also welcome.

I can’t part with Forst. I used to have a flat; my former partner, she let me use that flat in Hamburg when, in the wintertime, it gets rather dark and gloomy and muddy in Forst, but it’s different from city life, of course. In spring, summer, and also autumn, it’s beautiful. Today, I was up, I went into the toilet and I saw a beautiful sky with fog on the river, and I immediately grabbed my camera. I make photos all the time, because with each light—like daylight, bright sunshine, or dark atmosphere—you always have new impressions of the landscape.

Coming back to your question, apart from the beauty of the landscape, which really impressed me, of course, the thing was the lifestyle of the people and the lifestyle that was possible in this environment, which was, for me, a new experience. I came from Düsseldorf; I’d been living in cities with normal flats, and when I came to Forst, at the time—it’s really a funny anecdote—there was only one tap in the staircase with cold water. There was no sewage, nothing. There was just a pipe going through the wall, and everything went down just outside the house [laughs]. What I’m trying to say is, there was so much freedom to create your own living space, you know? Install heating, install proper sanitary things, and also, something I really enjoyed, I took a sledgehammer and just removed a wall that divided the space I could use, and just took out the wall to have a large room instead of two small ones. Try to do that in a flat in Düsseldorf! [Laughs]

So, the positive side was, we were really free. We could make music whenever we wanted to, nobody complained. We didn’t create much noise, but we had space, very much space to leave our gear. There were other people in Forst with whom we exchanged—like the people you see in the photos, you know, that was the kind of people, musicians came to visit. The basic thing is the freedom, really; it all comes down to the freedom.

What drew you to Roedelius and Moebius? How did you meet them?

I first met them in 1971. At the time, I was a member of Kraftwerk, and we had a concert in Hamburg, and Cluster were also on the bill. That was also quite a frightening story, because Kraftwerk was, of course, the famous band, but we were very democratic, and we asked the guys: “Would you like to start, or should we start?” And they made the wrong decision and said, “Oh, you go on first.” And then Kraftwerk started, and the music was so ecstatic, so rough, people really went wild. And when Cluster then started playing, people were furious! Quite a lot of people rushed to the stage and started turning around the speakers and disconnecting them, and they wanted us to keep on playing. So that was a memory I will never forget. We were playing in the university hall, Auditorium Maximum, with very steep—like, the seats went up very high, very quickly—and you looked up at this furious amount of people. I’m not sure whether all were furious, but very many people were, and they were very loud.

So that’s where I met Roedelius and Moebius, a very special experience. And then, two years later, when NEU! was offered to do a tour to the United Kingdom, we had a record label, United Artists, in the UK. And NEU! was sort of some kind of underground success, it was moderately successful then. The only problem was that Klaus Dinger and I didn’t have musicians that shared our idea of this fast-forward, running, rushing forward kind of music. Now, of course, looking back, the situation is quite clear to me. It had to be that way, because if there had been many other musicians with the same vision, then we wouldn’t have been alone, you know? This was our trip. This was our idea of music, and nobody around was able to understand or share that. And so, that was the tough spot.

And then I remembered this Cluster album—I think it’s Cluster II—with a track called “Im Süden,” which I really liked. I thought the melody on that track, which keeps on repeating, four notes [sings]—I could relate to that, and I thought, “I should visit those guys and check whether they, at least, could help Klaus Dinger and me put the NEU! music on stage.” And that’s when I took my guitar in 1973 and drove to Forst, and first only jammed with Roedelius. But that was enough; I didn’t need any more convincing, because it was obvious to me, and I think Roedelius felt the same, that we had a very special connection on these two instruments. For me, it was the first time that my guitar could respond and interact with another musical instrument like the electric piano Hans-Joachim Roedelius played at the time, which was treated in a special way; it had these fuzzy kind of sounds, and the delay machines he was using… This was spontaneous music that made sense from the first minute, and it was very inspiring. And so six weeks later I moved to Forst, and then Moebius joined in, and that was the beginning of Harmonia, which became a very important chapter in my musical development, and still is, of course, as a memory, a very important period in my life.

Now, it seems clear that Harmonia was a supergroup, or it’s easy to talk about Harmonia as a supergroup, but I get the feeling that it was not perceived as a supergroup at the time.

[Laughs] Yes, that’s very funny! Of course. NEU! was quite successful, really, in ’72, when we brought out the first album. You could go into Dusseldorf, into the club scene, discotheque scene, and you could hear “Hallogallo” and “Negativland” running in several clubs one evening, you know? That didn’t mean that we were suddenly pop stars, or something like that, but it was obvious that people really liked that. But, yeah, the supergroup thing is rather ridiculous because Harmonia was a total disaster, financial, commercial disaster. People were not willing to listen to Harmonia. It was really tough for me, because—strange—my old feelings for Harmonia were just the same as for NEU! I was equally convinced of Harmonia music as I was for NEU! and I was baffled that people didn’t share this feeling. Later on, of course, that experience made me start to think, and I understood that as an artist you have to rely on your own judgment. If you’re in love, if you’re convinced of what you do, you should stick to it and just hope that people catch up—which, of course, is what I did.

But it wasn’t easy, especially not for Harmonia and for the Cluster guys, because they also released some albums before I came to Forst, these two Cluster albums, but they didn’t make much money, they were really poor. Which made living not easy. But, I don’t know, looking back at those experiences, I’m rather happy, you know. We had the time to develop the music. If I look at young musicians today, they are sometimes pushed into fame before they have the chance to properly explore what they are really going for, and if success comes too easy, then it’s tempting to stop looking—which is what we had to do, you know, explore further.

After Harmonia crashed, after Roedelius and Moebius, actually, decided not to continue working as Harmonia—that was more or less their decision. I was unhappy, but the whole situation was unhappy, because after the release of Deluxe, that was another time when I thought, “Okay, now people will be with us, now they will discover our music.” Nope! They didn’t want to hear Harmonia Deluxe, they didn’t want to hear us live. There were some occasions when people cheered at our concerts, but the general situation was, there was one journalist in all of Germany—maybe one and a half—who really understood or supported our music. And hardly any radio play, any journalists in any situation, any position, that paid attention. They were all looking at American and English bands, and to a certain extent that has changed over the years, but even today I would think that it’s easier for me to get people into my concerts in Sydney or in Tokyo or wherever, outside of Germany.

I remember, when I played in Spain a few weeks ago, there was a band from France. Do you know Turzi? Have you heard of Turzi? We started talking, and they said “In France, nobody wants to hear us.” So maybe this is a standard sort of… we have this saying in Germany, something like “The prophet in his own land is never recognized.” Do you know that? Is there an expression in English?

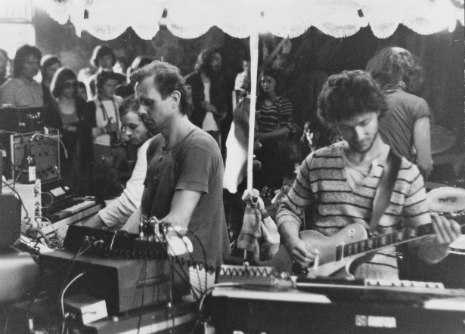

Harmonia with Brian Eno, 1976

There’s a similar expression in English, yeah. It makes me wonder, if you’d been able to tour…

Well, Harmonia did do concerts. Because that was the difference—a quite different situation to NEU! because Klaus Dinger and I as a duo didn’t work, but Harmonia, the three of us, if we had a good night, it was possible to create a really full music, with many details, with all kinds of aspects, and I was fascinated by that.

The only problem I had with Harmonia was, in the beginning, when we were still trying to avoid structures and, you know, just playing, just going onstage; one of us started playing something, and the others picked it up and carried the idea somewhere else. But sometimes, that took us two hours. And then five minutes were great, but one hour and fifty-five minutes were just searching, and searching, and people got really sleepy and confused [laughs]. Now, if you look at a track like “Ohrwurm,” on the first Harmonia album, on the second side, this is a five-minute excerpt from a recording from a concert we did in Forst in ’73, and I think that concert went on for two hours. And our friends, like Jerry lying on the sofa—the rather, how do you say in a polite way, strong guy [laughs] with a belly on the sofa—our friends, they were kind. They didn’t talk, they just sat there; I guess they were puzzled, and thinking, “Okay, what’s going to happen next? Is anything going to happen?” We were searching and searching and searching. And then, these five minutes came around, and in my opinion, these five minutes are pure magic, because this can only happen by chance. It’s three musicians paying close attention to what the others are doing, and then experiencing this magical situation when these three elements, the musicians, come together and create something special. I was not satisfied with these concerts when you had to—sometimes, we didn’t find anything, you know.

So I wanted to have more structure, and to be able to go onstage and not fear that it would end in a disaster because we had a bad day, and, I don’t know, a bad trip on the road, or some problems. That was a struggle that went on between Roedelius, Moebius more or less on one side and me on the other; I guess it had to do with my background in NEU! and also my inclination towards rhythmical and more structured music. As much as I, like I said, really loved these magical moments which we could create spontaneously, it was just not fulfilling to spend all that time searching, searching, and then sometimes not finding, and people being frustrated. So that was a struggle, and I tried to convince them to become more structured, more rhythmical.

Now if you look at a track like the one on this new album Documents 1975, and you hear these two live recordings, which of course represent better moments, when we were really in good shape, with Mani Neumeier of Guru Guru as drummer, and these other two tracks: the early version of “Deluxe,” the rhythmical instrumental, and especially “Tiki-Taka.” I was talking about the one journalist who supported us; he had a radio show, and he sometimes played our music. He was also the first to play “Hallogallo,” I think, on German radio. And he said, “Okay, if you record something, I will play it on the radio,” and that’s why we recorded “Tiki-Taka.” It’s so amazing. This music has been lying in my archive for 40 years, and although I have clear—being a musician, I guess, I remember every detail of the music, so when after ten, twenty, 30 or more years, I listen to it, I know exactly what’s going to happen. I guess it’s the same if you’re an architect, you remember all the individual elements in the structure of a house, something a non-architect would never notice. I have an architect friend, so I know that it comes, I guess, from your occupation, that you have specialized ways of paying attention to details.

Anyway, this “Tiki-Taka,” it’s so great to have this on an album now. I think it’s great, and so do some of my musical friends. Do you know Anika, by any chance? She’s a British DJ and also musician, she’s working on her second album just know; we wanted to do a project together, but I was too busy with Harmonia. She listened to that and said, “Michael, this is the best you’ve ever done.” I don’t know if I should be happy about that [laughs], but then I was really happy, because I know exactly what she means. This is so special, this music, and that’s why I’ve been cheering all these days since the box arrived. I’m so happy.

I invested a lot of time and energy in getting the material together for the box set. You know that Dieter Moebius was already rather ill; he passed away in July. He was involved in all the decisions. I made sure that he had the possibility to utter his opinion, or to reject ideas. But the work was on my end, you know. Roedelius was busy preparing his festival, I think; he had a big celebration this year, a festival in Berlin celebrating his 80th birthday in September, and also his Ohr festival, which was in August, I think. Anyway, everybody was rather pleased. I was very happy to see that, and a lot of positive energy went into that box, so now it’s time to celebrate and be happy about the box. It’s very sad that Dieter is not around to see it, but his wife sent me an email two days ago, and she also really likes the result, and she also believes that Dieter would have been very pleased with it, so this means a lot to me.

Don’t you have a show coming up with Roedelius?

That’s funny that you mention that, because I didn’t even know that he would be on the bill. We’re playing in Copenhagen in November—November fifth, I think. Actually, it’s my show, but suddenly it’s also Roedelius on the bill [laughs]. I think that was just the decision of the organizers of Jazzhouse in Copenhagen. I’m playing in Oslo next week, and then I’m playing in Düsseldorf, and Bologna in Italy, and then it’s Copenhagen, and then it’s Metz in France, and London in February, which the contract arrived today. And this will be a great thing, to bring the music to London again.

Who’s in your current band?

I have two musicians. Hans Lampe—you may remember the name; he was a member of La Düsseldorf, and he also played drums on the second side of NEU! 75. He joined me, I think, two years ago, and since then, we’ve become a really good team. There’s also a young guitar player who was in the band Camera. He’s no longer in that band, but we’re a trio, it works really well. We just came back from Spain, Barcelona and Santiago de Compostela, and we were in China in December last year, and, you know, it’s great to travel the world and to present the music.

Actually, have you been to China? Have you seen how the people react? It was amazing! I didn’t know what to expect, and then I saw the whole venue going crazy, running around in circles, having so much fun, smiles all over. It’s a very rewarding experience to travel the world with music, like I have the opportunity—privilege—of doing.

What were the Harmonia reunion shows like, from your point of view?

Ah, that’s interesting. That was 2007, when Grönland released Harmonia Live 1974, which was our best concert, I think, the best Harmonia concert back then. It was a bit tricky, to be quite honest. I had been touring with Moebius as Rother and Moebius; actually, that’s how I started playing live after more than twenty years which I spent only in my studio. In ’98, we did the first tour to the US as Rother and Moebius. We played at the Cooler in New York, and Chicago, Empty Bottle, and Spaceland [in Los Angeles], and then went up to Vancouver. Now, it’s nice touring. Back then, it’s strange—I’m getting lost in details, but I remember at the time I didn’t play guitar, because, I don’t know, I lost interest in playing the guitar for a while. And then, in the internet after the tour, I read comments: “Hey, great to see the guys, but what a bummer,” or something like that, “that Rother didn’t bring his guitar.” And then later, I started thinking about that, and now, I couldn’t imaging playing live without my guitar. It’s really beautiful, to have, these days, with the help of technology—do you know Kaoss Pads? I have two Kaoss Pads in my live setup, and so I can mess up the sound; it’s great.

Sorry, but you were asking about the reunion concerts. I was playing with Dieter Moebius at the time, and then, when Grönland started the preparations for the release of Live 1974, we got together in Berlin for a sort of reunion concert, and musically I think… how should I express it? We did some shows; we played at ATP in England, and then we also did ATP upstate New York, in Monticello. That’s very interesting that you ask me about that, because, somehow, it didn’t really work. But the people who listened to the concert, because there was a sort of battle going on sometimes—I felt that Roedelius and Moebius were, to be quite honest, in a way sabotaging my efforts in creating the spirit that I like to create in concerts, by playing the wrong harmony, the wrong key, something like that. Do you know, by any chance—unfortunately he died two years ago—Benjamin Curtis of School of Seven Bells and Secret Machines? Very talented young musician, and a good friend. He passed away, like I said. He suffered from leukemia. And I remember, he and his partner joined me, we drove together to ATP, where I played with Harmonia, upstate New York. And after the show, I was totally upset about this strange battle. And they told me, “No, no, Michael, it was great!” So, you see, the listener maybe experiences these struggles for direction in a completely different way. I was surprised by that, but, to be quite honest…

We then went to Australia. We did a really wonderful tour in 2009 where we played, I think, six shows in Australia. One on a mountain hilltop, one on an island in Sydney Harbor, with some really great success. I was very emotional about these struggles; they didn’t really make me happy, but I guess at certain times we were quite convincing [laughs], even the reunion thing. But then later, Roedelius decided to quit. I think he was furious with some decisions that were made by the label, and he also didn’t enjoy it.

Being independent, it’s totally okay now. Since then, things have become even better for me. In 2010, I got together with Steve Shelley of Sonic Youth and Aaron Mullan of Tall Firs and we did the Hallogallo tour, doing something like 35 concerts around the world. I’ve never in my life done anything near that number before, you know. So that was a great experience, and after that, for a while I asked this band Camera to be my backing band—from Berlin, three young guys. Since three years now, it’s this lineup, which is I think, sonically, even the best. And I feel privileged to be able to present music that way.

I wonder—it sounds like maybe there was some tension between you and Cluster all along, throughout the history of the group.

Yeah, well, the thing is, when I came to Forst, we were not Cluster and Michael Rother, we were Harmonia, and that’s really an important distinction, because—I mean, everybody’s entitled to their own memory; I think everybody knows that you have to be careful not to trust your own memory too much, because memory is forged, it’s shaped by, I don’t know, feelings, and looking back at situations 40 years ago, there’s enough room for interpretation and for lack of memory, for important details.

I was not interested in joining Cluster, or something like that. It was three musicians: the two individuals, Moebius and Roedelius, and the three of us were Harmonia, and in contrast to what you can sometimes read on the internet, it was not, how do you call it, like a “side project”? It was our main project for three years. It was our main project, and NEU! was sort of my side project. When I recorded the third NEU! album, I left Forst for a few weeks, but it was clear from the beginning that I would return and continue working with Harmonia. During my absence, Roedelius and Moebius recorded Zuckerzeit, an album which I am supposed to have produced, which is not true. [Laughs]

Really!

Well, I can explain the true story in a thousand interviews, and still the next one will be surprised. The truth, of course, is that we influenced each other. The exchange of ideas of working with Roedelius and Moebius shaped my idea for music, and struggling about music with me probably influenced their idea of music, you know? So that’s why Zuckerzeit sounds quite different from the Cluster album before. The story was that when I left to record NEU! 75, I left a lot of my gear in Forst, in our room, in our studio. And the guys asked me, “Can we use your gear, your nice four-track recording gear?” with which we would record with Brian Eno. I bought that four-track in early ’74, which was a big step forward, because for the first time I could sort of work like in a recording studio, because you could erase individual tracks. Only four tracks, but anyway, the guys, I told them, “Yeah, of course, you can use that,” and so, without asking me whether I liked the idea or not, they decided to give me credit as co-producer, and that’s it! Ever since then, people tell me, “Oh boy, Michael, so you produced Zuckerzeit! Yes, I must tell you, I can hear your influence!” or whatever. It’s so funny! It’s a bit different, but it’s a nice story, anyway.

But we did influence each other in a great way, and the inspiration I got from working with the two guys, this still has significance for my work these days. It was a very valuable experience for me, the time at Forst with them.

The only time I saw Dieter Moebius play, he was sharing the bill with Negativland, who are, of course, named after one of your songs. Moebius and Negativland’s Don Joyce died within a week of each other this year. I wonder if you have any impression of Negativland. They seem to be great fans of yours, because they named their band and their label after NEU! songs.

Well, I’m such a bad guy to ask about music, because I don’t actively follow what’s happening, and I know the name Negativland, that they exist or existed, but I think I’ve never heard a single note. So, unfortunately, I cannot give you any opinion on that. I thought it was a bit strange, that somebody took our name, our song… [laughs] Do they still play?

Yeah, they still exist.

I sometimes, when I travel around and play on festivals, I sometimes meet people I’ve known their names for decades and never met them. I may again meet Wire in Oslo, from the UK. Dieter Moebius—when was that?

It was three years ago in Los Angeles.

Dieter Moebius—that’s an important thing to say at the end. He was such a talented guy. He was so unique. He was absolutely unique in the way he worked with music, and it’s really very sad that he’s not around. He also still had his flat here in the same house, he and his wife. They only came for a few weeks every year, because they mostly lived in Berlin, and in recent years, we got very close again. It was heartbreaking to see him fade away, you know, this death of cancer and the way people just crumble. We hugged a few weeks before he died, [when] he came for a last visit. And it also meant a lot to me that he told me how much he… he was thankful for what I did for the Harmonia box set. That meant a lot, because Dieter was a man of great taste, not only in music, his complete lifestyle. I’m sure that we would have joined forces, sooner or later, again. But anyway, his music is around. I was at his funeral in Berlin, and two of his tracks were played there, that were chosen, I guess, by his wife. And I remember sitting there and thinking, “Yeah, this guy was so bloody talented.” [Laughs] You can exchange “bloody” for some more fitting expression if you want to use that, but he was really a great guy, a great musician. It’s a shame, in Germany, you get all these music prizes, and bands and artists get prizes—you think “What the hell?” And artists like Dieter Moebius, who really had something to offer for the whole world, you can hear his music around the world—I know musicians like John Frusciante have nearly all of his albums, I think, and many others—and they are sort of ignored in Germany.

It’s so surprising to hear, sitting in Los Angeles. I don’t know what you think of the term “Krautrock” [Rother laughs]—it’s an unfortunate term—but all these bands I think of as the national treasures of Germany, I come to find out that they don’t get the recognition in Germany that they ought to.

But then, lucky me, I can travel. It’s changing, slightly, in Germany. Even in Germany, some people are… there’s a big conference in Düsseldorf where I’m playing. Have you heard of ELECTRI_CITY? There’s a book by a German musician, former musician, and now they’re coming over from England, all these musicians like McCluskey of OMD and Daniel Miller. It’s not surprising that this is possible in Germany, a conference, and it’s becoming bigger and bigger. But, after all, I really enjoy traveling the world, to go to South America, or Australia, Japan, and present my music there, and get into touch with these cultures, and find interesting, fascinating characters there… so, who cares, Germany? [Laughs]

Harmonia’s Complete Works is available from Amazon and Grönland Records.