This is a guest post from Graham Rae.

In 2007, I interviewed Val Vale, of RE/Search Publications, and the late futurologist novelist JG Ballard, about a writer whom they were both very favorably predisposed to, William S. Burroughs. I talked to the amiable Val by phone, and sent JGB a few questions by mail, sending him a copy of an expensive science book I had received for review, An Evolutionary Psychology of Sleep and Dreams, to sweeten the pot. The answers are below.

These interviews originally appeared on the now-defunct website of the fine Scottish writer Laura Hird, and do not appear anywhere else online; have not done for years. Thus the references are somewhat dated, but at lot of the material, sadly, remains very much in vogue. I had only been in America for two years in 2007, and my views here seem somewhat naïve to me now, but, well, them’s the learning-immigrant breaks. So without further ado…

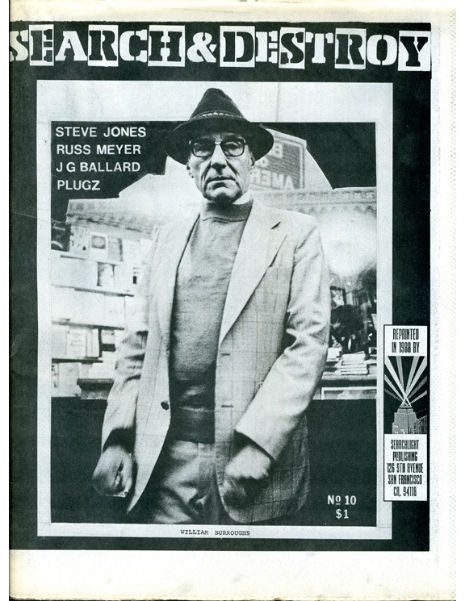

Foreword: Noted San Francisco underground publisher V Vale has been publishing since 1977, when, with $200 he was given by Beat poet Allen Ginsberg and poet/ City Lights bookstore owner Lawrence Ferlinghetti ($100 from each), he put out 11 issues of the Search And Destroy punk zine. In 1980 he started RE/Search, an imprint which still puts out infrequent volumes on subjects like schlock therapy trash movies, JG Ballard, punk, modern primitives, supermasochists, torture gardens, pranks, angry women, bodily fluids.anything and everything taboo and alternative and unreported was and is fair grist to Vale’s subversive ever-churning wordmill.

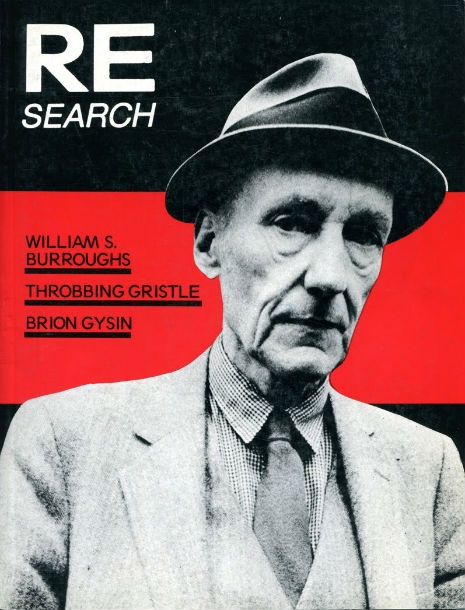

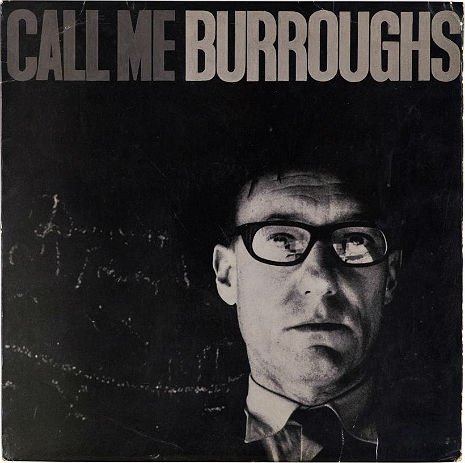

In 1982 he put out RE/Search #4/5, a three-section volume including William S. Burroughs, with the other two sections being about Throbbing Gristle and the artist Brion Gysin, WSB’s friend and collaborator who’d introduced the writer to the ‘cut-up’ method of rearranging his texts to show what they really mean.

The Burroughs section of the book include an interview with Burroughs by Vale (who is mentioned in Burroughs’ Last Words), an unpublished chapter from Cities of The Red Night, two excerpts from The Place of Dead Roads, two “Early Routines,” an article on “The Cut-Up Method of Brion Gysin” and ‘The Revised Boy Scout Manual’ which is a piece in which Burroughs muses revealingly on armed revolution and weapons-related revelation.

I talked to the amiable publisher about this interesting volume, but only about Burroughs, because he was the reason I wanted to read the thing in the first place; neither of the other two subjects much interest me, to be perfectly honest. It’s an interesting volume that any Burroughs enthusiast would definitely enjoy. So join us as we (me with occasionally incomprehensible-to-American-ears Scottish accent) take a trip down memory lane and talk about snakebite serum, dark-skinned young boys, the City Lights bookstore, independent publishing, aphorisms, Fox News’s hateful right-wing Christian conservative pop-agitprop, the madness of Tony Blair and avoiding mad drunks with guns.

And after the interview with Vale you will find the answers to a few questions JG Ballard was kind enough to answer me by mail about his own relationship with El Hombre Invisible.

V Vale Questions

Graham Rae: First off, how did you first encounter Burroughs’ work?

Vale: Oh, jeez. Well, I encountered Naked Lunch at college in the late ‘60s. He was like the cat’s meow. Burroughs and Kenneth Anger’s Hollywood Babylon—books like these. And it was obvious that Burroughs was this un-sane, slightly science-fictiony visionary, but he wasn’t really science fiction, he was extremely sardonic, that was his main appeal, with Dr. Benway and all that. And since I was more-or-less hetero oriented I think I more or less ignored all the references to young boys with blue gills and fluorescent appendages and whatever. That sort of went right by me like water off a duck’s back. It was only later that I realized that the imagery was kind of . . . how it was oriented. But what really turned me on to Burroughs was an article in a 1970 or ‘71 Atlantic Monthly magazine that came out with a huge excerpt in it from The Job, which is Burroughs’—I think it’s his signature book of interviews, it’s kind of the equivalent of The Philosophy of Andy Warhol (From A to B and Back Again). And so I took this magazine and underlined it and kept reading it over and over, making lists and trying to get all the books that he talked about. And then The Job came out and that became my Bible

Yeah?

Vale: Oh yeah, it’s totally important. Still important; it’s got so many ideas in it.

Well that’s the thing about Burroughs, isn’t it? It’s like this sort of surreal mercurial Braille, it’s very strange. I mean you read it, you go back to it and then you go back to it and then you get something different from it because you’ve got a completely different level of understanding of it, y’know, I think, personally.

Vale: Well yeah, that definitely can happen with any great book. And I spent so much time with ‘The Job’ and with that ‘Atlantic Monthly’ article. It was obvious that this was sort of like a philosophy of life. I mean, instead of saying you’re right wing or left wing politically, you could just say, Well, I’m a Burroughsian. There should be almost a Burroughsian political party making fun of authoritarianism all across the entire political spectrum.

I’ve got that party in my head that goes on 24 fucking 7, man. Right. When and how did you first contact Burroughs?

Vale: Well I was already working at City Lights Bookstore and one of the perks of working there was that you got to meet all the so-called Beatniks and you were already in the in-group.

Did you meet like Ginsberg and that then, I take it?

Vale: Oh yeah, sure. The legend is that Ginsberg gave me my first $100 to start publishing. It’s certainly true, but I wish I had made a Xerox of the check, and I wish I had made a Xerox of the check that Ferlinghetti gave me, too. But you know, back in those days you didn’t have a home Xerox machine, you had to go to a corner facility and spend ten cens on a Xerox. Believe it or not, ten cents for a Xerox was a lot of money in 1976 or so.

Especially when you don’t have much money.

Vale: Especially when you’re living on minimum wage from City Lights, but you know you would parlay that, you’d stretch that out by: you’d get such a low income you’d qualify for food stamps, for example. They still give out food stamps—I see these old Chinese people using them still, but I hear they’re really hard to get now. But they used to be easy to get.

Just as well for you. So did Burroughs come into the shop one time, or what?

Vale: Yeah, well, he came through on a reading tour like authors tend to do and y’know I had to kind of figure out an angle on how to kind of stand out, because everybody wants to meet Burroughs. But you know he probably likes—him being this pale blondish Midwestern background, I found out later that he tends to like darker-skinned young boys, of which I qualified. But, being hetero of course—I didn’t know these things at the time, and I knew the point of intersection would be firearms, because I grew up in a very small desert town and for a certain several years of my life, until I got arrested by the police, I spent a great deal of time by myself walking in the desert with my .22 rifle and pistol, sort of shooting at anything that moved. But actually I didn’t—after I killed my first rabbit I was utterly horrified because it took about 20 shots pumped into the little quivering body before it finally stopped moving. It was kind of a gross experience. The .22 long rifle cartridge just isn’t that powerful, I guess, even for a 12 or 14 lbs rabbit.

Did you talk to Burroughs about guns, then?

Vale: Oh yeah, and I also knew a lot about guns, because someone just gave me all these gun magazines and I just devoured them and memorized them and then I sent away for free catalogues and I sort of fantasized going away to South America and being kind of an explorer. And, you know, I’d have all these certain state-of-the-art firearms and gear and all that. And so I did know quite a bit about the history of firearms. And so it was very easy to talk to Burroughs about that. He was up-to-the-minute; up to the day he died he was up-to-the-minute on state-of-the-art firearms and. He knew a lot more about knives than I did. He taught me how to throw knives, but I don’t think I’m as good as him. He’s quite good. I mean, have you ever tried to throw a knife?

Not really, no.

Vale: Oh. Well, there’s an art to it. First of all, the knife has to have some balance. Then you grab it by the point, more or less, and then you do a little flick of the wrist and elbow at a spot on a side of a barn, for example. And under Burroughs’ help I got so I could stick a blade in most of the time. But it’s not my preferred choice of weaponry, by any means.

Why was Burroughs so gun-obsessed?

Vale: Why was he? Because he believed in the right to bear arms, he believed in, y’know, the foundation of this country is the right to have a gun in your household and rise up against the government if the government should turn fascist—which of course—which of course it has. But of course everyone’s so brain-dead and stupid and dumbed-down now they’ve forgotten all this. He also believed that—or let’s say he respected—that little aphorism which you probably haven’t heard, which is: ‘God made man, but Samuel Colt made them all equal.’

I’ve heard that aphorism because it’s in a Manic Street Preachers song.

Vale: Wait a minute, say that again?

I have heard that saying because it’s in a song by the band the Manic Street Preachers. The lyric goes “Fuck the Brady Bill / fuck the Brady Bill / if God made man they say / Sam Colt made them equal.”

Vale: He’s right. (laughs)

I know all sorts of strange things you would not credit me with knowing being Scottish, Mr. Vale.

Vale: That’s right. I shouldn’t, I mean I wouldn’t doubt it. And I’ll tell you why. I’ve said this before: you Scots and you Brits and you Welshmen and whoever in the UK, you’ve all gotten, even in the worst country parish, you’ve gotten a far superior education to us Americans. I’d say it’s ten times as good as the average.

I don’t really have much of a frame of reference for that, but I’ll take your word for it. How close was your friendship with Burroughs? Did you meet him over the years at certain points, or….

Vale: Oh, I wouldn’t claim it was deep. Let’s see . . . I talked to him several times in San Francisco. I spent a whopping ten days with him in 1988 because James Grauerholz (executor of Burroughs’ literary estate) was going out of town and I somehow timed it so I was there in his place and running all the errands that James ran for him. And then James came back I think a day before I left, and we went to a big dinner some woman made, so there were like, y’know, fifteen people there or something. And then after that I went and visited him just before he died in 1997 for several hours. And so, I don’t know, but I think the early conversations must have been a little refreshing for him. I have the feeling that I was the first young person that he’d met who knew a lot about firearms and had a passion for it more or less just like he did. And so he could tell I was real. (Laughs)

You weren’t like a dilettante starfucker, y’know, ‘Mr. Burroughs I’ve read all your books,’ you were like ‘tell me about the Magnum .45’ or something.

Vale: (Chuckling) Well, there is no such thing as a Magnum .45, but there is a .44 Magnum.

Ah well, you see my extensive knowledge of firearms. I have fired guns once with a friend of mine from San Francisco, but apart from that they’re not something I’ve ever really been interested in.

Vale: Ah no, you don’t need to, and I haven’t been interested in at least 25 years or something like that. I went through about three intensive years from around age 14-16 until I got arrested, then I…

What did you get arrested for?

Vale: I just . . . me and this other person got arrested for being on private property, with a firearm, which was frowned upon.

Yeah.

Vale: Well, we were just going on this property to see if we could just—like, we were in a car and we were going onto this property to see if we could maybe shoot some rabbits. Because they tend to freeze in the glare of the headlights of the car, they make easy targets. But before we could do it some policeman came out of nowhere—he must have been bored and started following us, and he hauled us to the station. I wasn’t even sixteen then, the other person was sixteen .cos he had just gotten his car driver’s license. His parents got very angry with me and forbade him to associate with me anymore. I was considered a bad influence, apparently.

Teenage boys with guns, man…

Vale: Well no, I was the only one who had guns.

You sound like a Burroughs wet dream there, a teenage boy with a gun.

Vale: (Laughing) I dunno, I don’t think that’s the only qualifier. See, I like to read, I always liked to read, and so I just devoured this huge pile of gun magazines. I can tell you the titles: they were ‘American Rifleman,’ ‘Outdoor Life,’ ‘Sports Afield,’ and ‘Field And Stream.’ I like memorized all the articles and then I started sending for all these free gun catalogues you could get then, and catalogs of outdoor wear and gear, trying to become sort of an armchair expert on all these things. You know, like snakebite—what to do if you have a snakebite. I think I mail ordered a snakebite kit, for example.

That sounds like a kind of Burroughsian random autodidact trajectory, you just go where your obsessions take you.

Vale: Yeah, I don’t even remember who gave me these magazines, but these magazines changed my life (chuckling) for a few years.

How was Burroughs when you lived with him for ten days, how did you find the man? I mean was he crazy, or was he quite placid, or did he try and shoot you, or…

Vale: He’s like this Harvard country gentleman, completely civilized and well-mannered and full of puns and always quoting Shakespeare—things like that. He must have memorized a lot of Shakespeare in his day. How can I say it—he’s both. I mean, he did go to Harvard, you know, which is the best college or university in America. But he also had a lot of street experience, having been a junkie and also an exterminator. “Got any bugs lady?”—you’ve read that. And I think he was a farmer, too; tried to be a farmer in Texas. And then he of course went through that whole gay underground scene in New York City and Mexico City and Tangier and all that. And so he’s kind of been exposed to a full spectrum of humanity. High and low culture, completely. And so his conversations can go all over the map, depending on your interests.

And your intelligence level as well, eh?

Vale: Well, I guess. But you know what I’ve found is that there are so many levels of intelligence—I never judge anybody that way, because someone who may be—let’s say their culture doesn’t overlap with your very much—you can still learn a lot about something you knew nothing about. Then you realize this person knows a lot more than you. Especially in a city, or I suppose in the country, too. Even, you might say, the dimmest lightbulb can be surprising; you just have to tap it.

The dimmest lightbulb still gives out an illuminating flicker or two.

Vale: Well, sometimes a flash of an illumination! (Laughs) You’d be surprised, in fact surprise is what life is all about.

Back to your William S Burroughs volume. Why did you put it out and how did you choose the pieces that went into the book?

Vale: Well I didn’t choose them. First I got to do the interview and then I simply asked James Grauerholz for some unpublished pieces that I could use. And it was as simple as that: he sent me them and I used what he sent me. But of course the reason why I liked Burroughs can be summed up in one word: either “anti-authoritarian” or the words “Control Process.” I mean he is all about trying to decipher and uncover the workings of the Control Process, as he named it, by which we’re all controlled in ways in which we don’t even realize, which is the scariest thing.

That’s very true. Did you see the documentary Outfoxed?

Vale: No.

I was watching that the other night. It’s about Fox News. They asked all these questions like ‘do you believe Iraq had weapons of mass destruction’ and ‘do you believe Iraq has an Al Queda connection?’ The numbers were consistently… let’s just say if you did not watch Fox then 17% of you believed that Saddam Hussein had weapons of mass destruction or, you know, had an Al Qaeda connection. And if you watched Fox News the numbers were up in the 70-75% range because it’s just pure bullshit disinformation.

Vale: Oh, it’s lies.

It’s pure lies, it’s bizarre. That’s one thing that’s fascinated me since I came to this country is attack dog politics, these fucking idiots like Ann Coulter and Bill O’Reilly and Rush Limbaugh and all these fucking muppets, you know?

Vale: Well, they’re just propagandists. There seems to be some sort of weird conspiracy to bamboozle most of the American populace and (sighs) it’s working. I mean, I printed a statistic in one of my newsletters awhile back which is that these right-wing conservative Republicans, I don’t know how many of them, raised $3 billion and over the course of the last ten years funded 45 think-tanks and all these think-tanks worked on just how to take control of the country. And they darn near worked. Now, of course, as we just saw this shift in Congress where the House and the Senate are now back to being under Democratic control despite all the dirty tricks and think-tanking of the Republicans and all their illegal phone-calling campaigns, impersonating Democrats, and all the dirty tricks they did. And I’m surprised this thing happened because I was sure that the Republicans had total control of all the voting machines. And so I was amazed that this happened at all, this Democratic shift, but of course today this bill got passed making it illegal to—you can be thrown in jail if you demonstrate in front of a store, because the basis is that the store can sort of easily sort of prove that you damaged their business and they got less income because you were standing in front with a picket sign or something, or a boycott sign. And the bill made it easier for you to be thrown in jail now for doing this.

I think they did this in Britain as well, y’know, it was just basically to stop people demonstrating, if you’ve got more than a few people in one group you’re obviously anarchist rabble-rousers and we’re going disband your group because you’re obviously up to no good. The fact that demonstrating has nothing to do with it, you’re just scum.

Vale: In London they used to have Hyde Park and there used to be all kinds of political rabble-rousers talking there and that was permitted. What happened to that?

Britain is America Lite. Tony Blair is a madman. He is finally going to be going, but it’s just gone just as bad as the spin culture in America, it really has, and it’s worse because it’s even more stupid, it’s not as well-financed or thought through, it’s just a pale irritating imitative shadow of the American surreal experience with politics. It really is a sick joke. And Tony Blair’s just a deeply corrupt man, but of course he’s got that whole sort of ‘God’s on my side’ pathological nonsense as well, you know. I’ll tell you something, one of the best expressions I ever heard used was “Time to look beyond this rundown radioactive cop-ridden planet.” It’s just perfect.

Was Burroughs pleased with the way your book turned out?

Vale: Oh yeah, he loved it. He was happy because it was like the first time he was ever shown holding a firearm. No one had ever dared print photos like that.

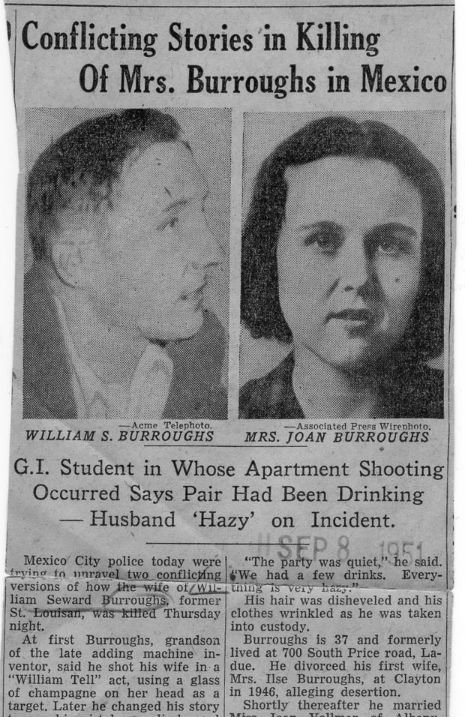

Too scared of the controversial aspects with the Joan Vollmer incident (Burroughs shot and killed his wife in a drunken game of ‘William Tell’)?

Vale: I think people just weren’t interested; no one had ever thought (to do it). And then of course later on someone brought out a book by Burroughs called Painting And Guns, a little tiny Hanuman Press book in which someone interviewed him, I guess, on painting and guns. (Laughs) I sort of paved the way for it to be okay.

The whole Burroughs thing with guns, I mean… bearing in mind that I come from a country that doesn’t really have a gun culture, and around nine years ago there was a primary school - which is a school for kids from four or five until eleven - it was in Dunblane and there was a shooting, so they basically disarmed the country after that. So American and British gun cultures are vastly, vastly different things. I dunno, it’s just something that some people like and some people don’t. I think in Britain it’s regarded as a kind of Republican right-wing, NASCAR-watching, beer-guzzling kind of thing to do, go and shoot your guns in the house.

Vale: I couldn’t say about England. See, here we’ve got the whole myth about the Wild West, and the taming of the West, and the guns that tamed the West kind of thing, y’know, the Winchester repeating rifle - Winchester .73 they call it, the Colt Peacemaker they call it, the six-shooter single action pistol—you can’t just pull the trigger, you have to pull the hammer back first. And of course they’re not talking about who was killed: all the original populace, all the original inhabitants of America. Someone was telling me about a very interesting-sounding book which I have to find called 1491 which is all about America before Columbus got here. And they’re trying to do a scientific and anthropological - or rather archaeological, too - analysis of, like, Indian mounds.

You printed an edition of The Atrocity Exhibition by JG Ballard with an introduction by Burroughs, right?

Vale: That’s correct.

Did Burroughs rate Ballard’s work as much as Ballard rates Burroughs’? Do you have any idea what his opinion on Mr. Ballard’s work is?

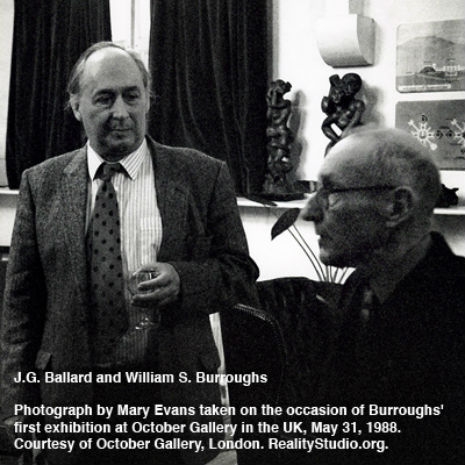

Vale: That is difficult to ascertain because Burroughs was more, how can I say—he was actually quite generous to people who wanted recommendations or blurbs or whatever you call them for their books. And I don’t think he would have written that piece on Ballard if he hadn’t meant what he said. So that’s all I can go by. And they did meet once, very briefly, in England I think. I think it’s talked about in one of the books, the Quotes book or the Conversations.

Do you have any favourite piece of Burroughs memorabilia that you own?

Vale: Oh, that I own? Gee, I guess I had a target that he shot. I took him out shooting and I asked him if I could keep the target he shot, and he autographed it. And he had a spray can in his studio in Kansas—it was a used spray can, used in making his artwork. He’d sprayed it a bunch of different rainbow colors. I asked him if he would autograph it and he did and I kept it.

Did you rate him as an artist? Did you like him as an artist, a painter, as opposed to a writer?

Vale: (Misunderstanding) Well, he’s come up with the genius quotes to live by, and he’s invented these sardonic characters, Dr. Benway or whoever they are. For all that alone he deserves to go down in history.

Yeah, that’s true, but…

Vale: And he and Ballard are my favourite two writers of the 21st century.

Um what I mean is, did you like Burroughs’ paintings and stuff as opposed to his writing?

Vale: Oh, that’s the question!

It’s the accent, pal, it’s the accent.

Vale: (Chuckling) Yes! Well, you know, the way I always consider a writer is that everything they write and everything they say is all part of one big work and that includes the diaries and the journals and the paintings and the collages and the jokes and the whole nine yards. And sure, I don’t mind his paintings at all, but you’re talking to a man whose gold standard for paintings is Hieronymus Bosch triptychs. And they’re so complex there really isn’t much that can stand up to that. It sort of blows out of the water, say, most of Andy Warhol’s single paintings, for example. I mean, there’s just so much narrative, or just so much you can read into the Bosch triptychs, that there’s very little that can stand up against that, if you’re running a competition.

You know the artist Joe Coleman?

Vale: Of course!

There’s a strange kind of Hieronymus Bosch-like—there’s so much detail in the paintings he does. They’re very beautiful, but they’re quite disturbing.

Vale: Yeah, he’s one of my favourite living painters, there’s no doubt about that.

He’s a character all right.

Vale: He was in the first Pranks book.

That’s right, he was. I’ll tell you what, we’ll have one last question about Burroughs. What do you think Burroughs’ major literary legacy contribution was, or will be? What do you think his major contribution to the literary world will be?

Vale: (Pause) Little aphorisms, y’know—that’s the way that somebody like Schopenhauer and Nietzsche will probably be remembered. I mean I kind of consider Burroughs to be more of a philosopher than a writer, for me, but there are people who consider him a writer too. He’s definitely captured a lot of great memorable, funny lines and dialogues and things like that. For me, of course, it’s the interviews in the books like The Job and The Burroughs Files and—what’s that other one, The Adding Machine, as well as The Complete Interviews which aren’t complete, of course. Every book that says ‘complete’ never is, I’ve found. And just the general persona, being like a, how can I say—he’s extremely libertarian in all of his thinking and very fair-minded, but he also liked to shoot and own guns and knives and he was quite concerned with the problem of self-defense (chuckles and puts on sarcastic tone) as any red-blooded American oughta be.

I read that Interviews and I saw that in Burroughs: The Movie where he as going on about attacking people , if people attacked you, you could cut their throats or shoot them and it was like (dubious voice) “okay.” There’s a man you wouldn’t want to be around when he was drunk with a gun in his hand, y’know?

Vale: But he hardly ever got drunk and when he did he didn’t play around with guns. He was properly trained, he didn’t—there’s actually rules about the handling of firearms. And most people nowadays don’t learn them, but you really, truly, never point a gun at anyone, even if you think it’s unloaded. You just don’t play with guns and you don’t really mix guns with alcohol. I mean there’s, like, basic rules.

Ones that Burroughs could have learned a lot from had he learned them earlier in his life.

JG Ballard Questions

Graham Rae: When and how did you first encounter Burroughs’ writing?

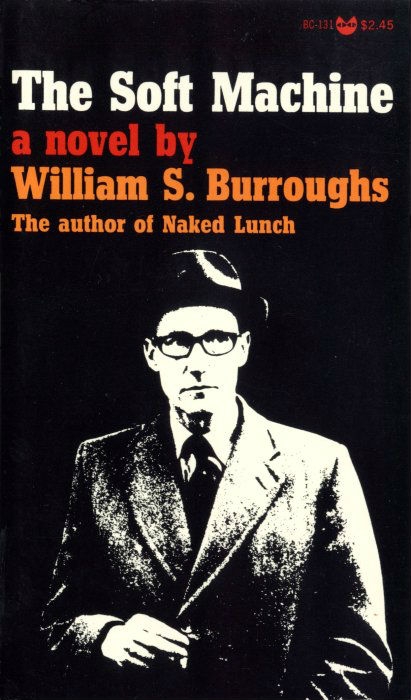

Ballard: I first read Naked Lunch, Soft Machine + Ticket T(hat) E(exploded) in about 1960 or so, in the green Olympia Press editions given to me by Michael Moorcock.

What did you think when you read his work, and what was it about it that stood out?

Ballard: I was absolutely overwhelmed - my faith in the novel, which had been fading for years, was instantly restored - what stood out? Sheer originality, humour, the unique eye, the coherence of his apocalyptic vision.

When and how did you first meet Burroughs?

Ballard: I met WSB in about 1965 - in London, through Bill Butler, an American poet, now sadly dead, who ran a little publishing house in Brighton.

How many times did you meet him over the years, where did you meet him, and were any of the conversations about literature?

Ballard: I met him at various places over the next 30 years - at his St. James Street flat, at a rock concert near Brighton, at various parties - I remember that he cooked a tasty roast chicken at the St James flat, + then demonstrated with the carving knife where best to inflict a fatal stab wound - he kept away from the windows, claiming that the CIA/Time magazine were watching him from a disguised laundry van - in some 20 meetings we never discussed anything literary.

What is your favourite Burroughs book?

Ballard: Naked Lunch.

How did you get Burroughs to write the introduction to The Atrocity Exhibition?

Ballard: Grove Press arranged his superb introduction.

What do you think Burroughs’s major literary legacy will be?

Ballard: Risk everything, gain everything.

This is a guest post from Graham Rae.