The writer James Kennaway was working as a publisher’s agent when he first heard talk of the sensory deprivation experiments carried out at McGill University in Montreal, Canada, during the early 1950s.

Kennaway’s job entailed traveling across England seeking out academics and scientists to contribute texts for Longmans catalog of books. The stories he heard at Oxford University were just idle chat shared over cups of milky tea or warm beer in pubs. Rumors someone had heard from somebody else that students were being paid to undergo a week of sensory deprivation—so far no one had succeeded. Though still an unpublished author, Kennaway knew he had found material for a very good story.

James Kennaway was born on 5 June 1928 in Auchterarder, Scotland. His father was a successful lawyer, his mother a graduate of medicine. The younger of two children (his sister Hazel was born in 1925), Kennaway’s early childhood was one of tradition and privilege, with the expectation that he would one day follow in his father’s footsteps.

His childhood idyll ended when Kennaway’s father died in January 1941. Though at a preparatory school in Edinburgh, the twelve-year-old felt obliged to take up the role as “male head of the household.” He suppressed his own emotional needs and began to write letters to his mother full of the advice and emotional support he felt his father would have given.

The untimely death made James feel that he too would die young, and this early trauma, together with the pressure he felt to succeed at school led to a fissure in his personality that would widen with age. Kennaway’s biographer, Trevor Royle described this gradual change of character as:

James was the sophisticate, Jim the “nasty wee Scot”. Later, he came to characterize the split as James the domesticated man constrained by society and Jim the artist who should be allowed any amount of license.

Or, as Kennaway later described it:

James et Jim, man and artist, wild boy and introvert.

At school “James” was the likable, eager-to-please pupil; while “Jim” was beginning his first thoughts towards a career as a writer—as Kennaway explained in a letter to his mother:

...I feel I have been granted with more than one talent; in such a life my talent of sympathy would shine but my other talents would lie buried. On my part I would get lazier and fatter every day. I might however do this at the same time as I write and really go in for writing, but I must learn more about the English language before I can write any stuff worth reading.

After school, Kennaway carried out his National Service in the Queen’s Own Cameron Highlanders before going up to Oxford to study Modern Greats (Politics, Philosophy and Economics or P.P.E.). It was here he met Susan Edmonds, whom he married in 1951.

After university, Kennaway worked for a publishing firm, and in his spare time, started work on his first novel Tunes of Glory.

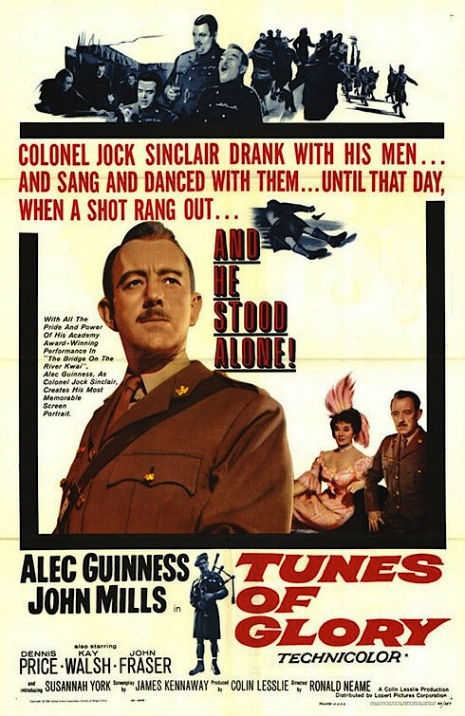

Published in 1956, Tunes of Glory was the story of a psychological battle between bully Major Jock Sinclair and war-wounded Lieutenant Colonel Basil Barrow for control of over a peacetime battalion stationed in a Scottish army barracks. The story had been inspired by many of the people and events Kennaway encountered during his National Service.

Max Frisch noted in his novel Montauk that a writer only ever betrays himself; this is true for Kennaway who channeled the experiences of his life through the prism of his writing.

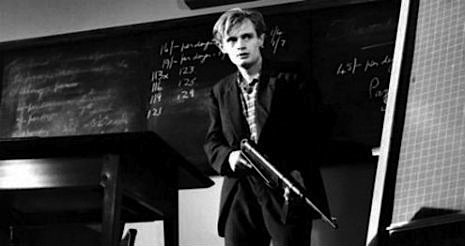

The book’s overwhelming success brought Kennaway more work as a writer: a commission to write an original screenplay. This became Violent Playground, which was filmed in 1957 with Stanley Baker, David McCallum, Anne Heywood and Peter Cushing. Its story of a juvenile delinquent holding a classroom of children to ransom was inspired by real siege in Terrazanno, Italy, when two brothers, armed with guns and dynamite, held ninety-nine pupils and three teachers to ransom. The brothers threatened to kill their hostages unless various demands were met. The siege ended after a teacher attacked and disarmed the brothers allowing the police to rescue the children. Kennaway followed the story in the papers, keeping numerous press clippings, and using the story for a key scene in his screenplay.

The following year, Kennaway was commissioned to write another film, this time he relied on the stories he had heard from academics at Oxford in the early 1950s.

The term “brainwashing” was first used by journalist (and CIA stooge) Edward Hunter in an article he wrote for the Miami News, 7th October 1950. Hunter used the term to bogusly describe why certain U.S. soldiers had allegedly co-operated with their captors during the Korean War. Simply put, Hunter was suggesting the Chinese had used various psychological techniques to create a false sense of friendship with which they could undermine, reprogram and brainwash American soldiers. This led to Western governments commencing their own brainwashing experiments.

In June 1951, a secret meeting at the Ritz Carlton Hotel in Montreal saw the launch of a CIA-funded, joint American-British-Canadian venture to fund studies “into the psychological factors causing the human mind to accept certain political beliefs aimed at determining means for combating communism and democracy” and “research into the means whereby an individual may be brought temporarily or perhaps permanently under the control of another.”

Dr. Donald Hebb of McGill University received a grant of $10,000 to examine the effects of sensory deprivation. Volunteers were paid to lie on a bed, cradled in a foam pillow (to block out external sounds), their arms wrapped in cardboard tubes (to limit movement and sensation), whilst wearing white opaque goggles. Without any external stimuli and only short breaks for testing, feeding and use of the toilet, the volunteers quickly began to hallucinate—seeing dots, colored lights, and faces. The experiments had disturbing affects on the volunteers with only a few managing to continue beyond two or three days—no one lasted the week.

The experiments progressed with the use of flotation tanks that became central to Kennaway’s screenplay.

In an article “The Pathology of Boredom” published in Scientific American, one of Hebb’s associates wrote:

Most of the subjects had planned to think about their work: some intended to review their studies, some to plan term papers, and one thought he would organize a lecture he had to deliver. Nearly all of them reported that the most striking thing about the experience was that they were unable to think clearly about anything for any length of time and that their thought processes seemed to be affected in other ways.

It was also noted during these experiments that the volunteers were overly susceptible to external sensory stimulation—making them open to ideas or beliefs they may have once opposed. In A Question of Torture, professor Alfred McCoy of Madison University, noted that during Hebb’s experiments “the subject’s very identity had begun to disintegrate.”

When stories of these experiments first filtered through to Kennaway in the early 1950s, he recognized their importance and stored them away for future use. These stories provided the basis for a screenplay that he originally called The Visiting Scientist or If This Be Treason. The script dealt with the use of brainwashing by sensory deprivation to investigate the suicide of a scientist. Unfortunately, the screenplay was thought too way out for its time and was shelved.

Let’s not forget, this was 1950s Britain in the last days of Empire and at the start of an attempted institutionalized socialism: a world of rationing and free health care, bomb sites and new towns, poverty and taxes; where Germany was now the ally, and communist Russia the feared enemy, and the very real possibility of a nuclear holocaust. Against such a backcloth, there was little public knowledge of brainwashing or its use by Allied or enemy governments. There were, of course, the works of fiction about its potential such as George Orwell’s 1984, Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World, David Karp’s One, and Richard Condon’s The Manchurian Candidate, but these dealt speculative fictions or specifically targeted enemy activity, rather than the grim reality Kennaway posited on the work of western governments in The Mind Benders.

Kennaway continued working on his second novel Household Ghosts (later filmed as Country Dance with Peter O’Toole and Susannah York), and adapted Tunes of Glory for a movie starring Alec Guinness as Sinclair and John Mills as Barrow.

The success took Kennaway to Hollywood, where he had meetings over various movie projects, including one with with Alfred Hitchcock about The Birds—a project he failed to win after suggesting most of the action should happen off screen. Kennaway’s time in Hollywood also allowed him to give family man “James” a rest and permitted “Jim” to indulge in extramarital affairs.

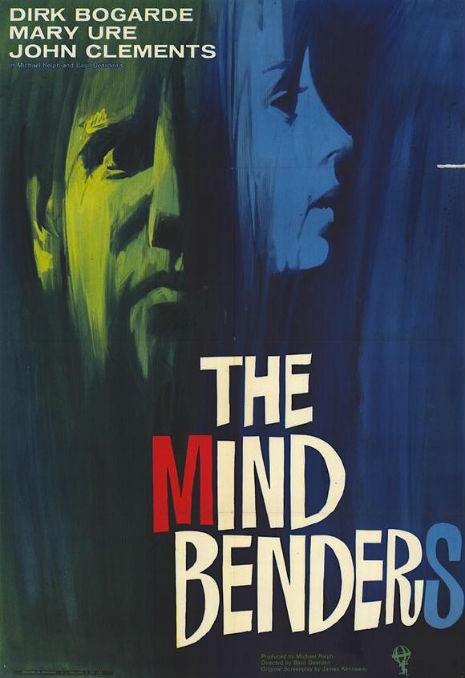

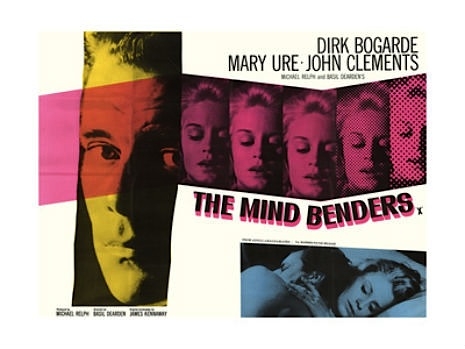

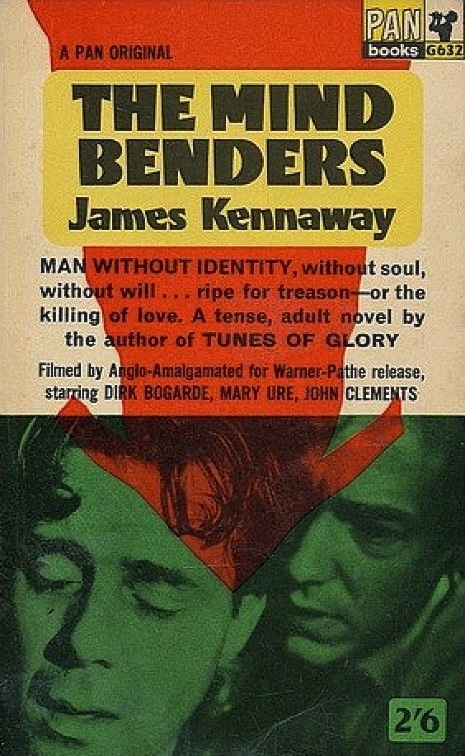

During this time, director Basil Dearden managed to convince Dirk Bogarde to star in Kennaway’s script about brainwashing now titled The Mind Benders. With Bogarde as star, the movie was greenlighted and production began in 1962, ten years after Kennaway had first heard the stories about sensory deprivation, and almost five after he started writing the screenplay. The quality of his script encouraged the producer Michael Relph to suggest a tie-in book. This was originally planned to be written by a hack, but Kennaway decided to author the novel himself as he thought it would add to his oeuvre.

Though Kennaway spent most of his life away from his native Scotland, he is very much a great Scottish writer, and The Mind Benders is very much in the tradition of good Scottish Literature, with a similarity of style to Robert Louis Stevenson and John Buchan.

The book also relates to the concept put forward by literary critic George Gregory Smith of “Caledonian Antisyzygy” or the “idea of dueling polarities within one entity.” This notion of two sides to the Scottish psyche has been reflected in Robert Louis Stevenson’s Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, James Hogg’s The Private Memoirs and Confessions of a Justified Sinner, and some of the writing and poetry of the great Hugh MacDiarmid.

These “dueling polarities” appear in The Mind Benders through the fictional Dr. Longman, who also acts a cipher for the division in Kennaway himself, between “James” and “Jim.”

When the film was released, the English critics hasrhly condemned The Mind Benders refusing to believe Britain or its Allies could be involved in such heinous practices. The novel faired far better winning considerable praise for its writing and powerful storyline:

‘A fine fusion of science and imagination, this novel belongs on the same shelf as the books of William Golding and George Orwell’s 1984.’ – Washington Post

‘[E]xciting . . . provides more than a few frissons and a story of considerable sophistication and fascination.’ – Kirkus Reviews

‘Kennaway’s treatment of this nightmare and his horrifying suggestions for bending minds makes this a first-rate thriller.’ – Times Literary Supplement

The Mind Benders begins like a spy novel, with Major “Ramrod” Hall, one of MI5’s counter intelligence agents following a professor Sharpey—a scientist Ramrod thinks may be working for the Communists. What follows is comparable to the best of Len Deighton and John le Carré. But a spy novel was not Kennaway’s intention, as about a third of the way through, the novel changes into an evocatively described section of the loving relationship between Dr Longman, his wife Oonagh and their children, which perhaps offers a peephole into Kennaway’s own home life. This romantic idyll offers counterpoint to the horrors that follow, once Kennaway takes the reader into “Strictly Frankenstein country…”

The Mind Benders is a good film but an even better novel; an intelligent tightly written page-turner that like a stone dropped in water ripples in the imagination long after reading.

During the sixties, Kennaway continued with his highly successful career as a novelist and screenwriter. He died suddenly of a heart attack whilst driving home, just prior to the publication of his last and arguably greatest novel The Cost of Living Like This. James Kennaway was forty years old. He did die young, as he feared, like his father.

The excellent Valancourt Books have just republished both The Mind Benders and The Cost of Living Like This, details of which can be found here.