In 1922, T. S. Eliot’s poem The Wasteland was published in the Criterion magazine. It was read by no more than a handful of people. The poem was then republished in book form in a limited edition of 450 copies. Within a decade, The Wasteland was considered one of the greatest poems of the twentieth century and its modernist influence continues to this day.

In December 1977, the sound of the future arrived when a two-piece band called Suicide released their self-titled debut album to little acknowledgement or fanfare except from a few astute record critics in England. The American press mostly reviled it. Record buyers ignored it. Yet, within a decade, Suicide was considered one of the most important and influential album releases of all time.

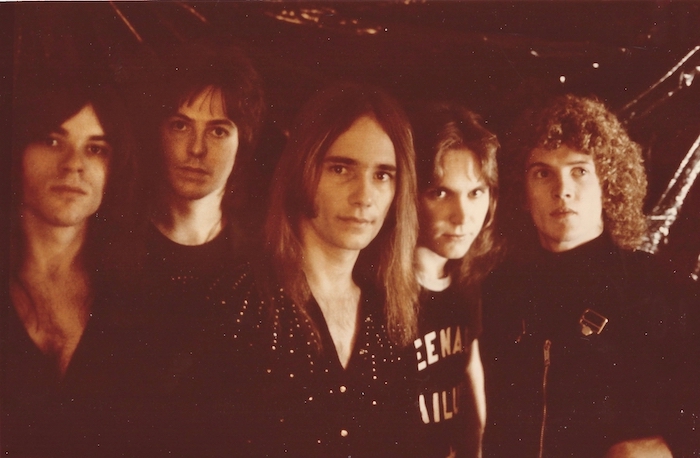

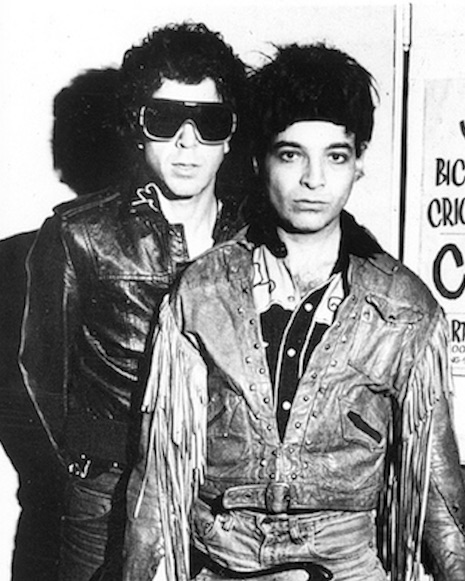

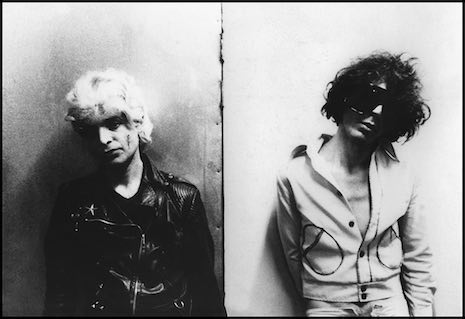

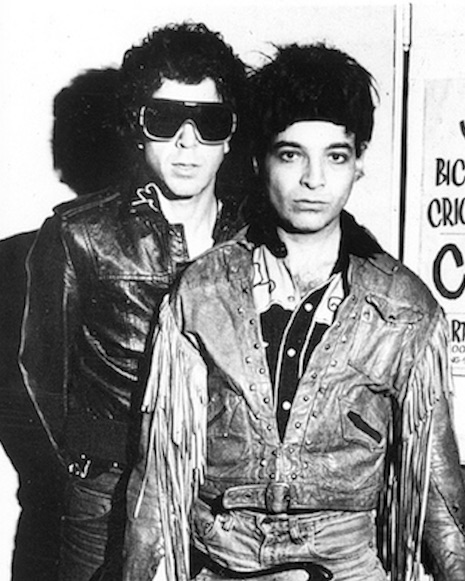

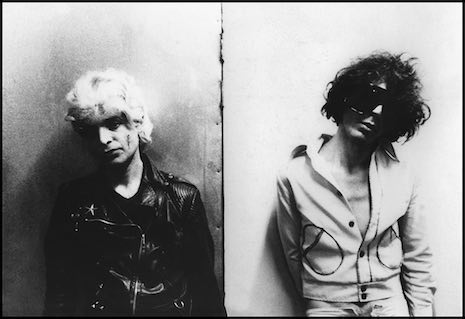

Suicide consisted of Martin Rev (keyboards) and Alan Vega (vocals). This thirty-something musical pairing of radical mavericks stripped down rock ‘n’ roll into its constituent parts and reinvented it as a new, pulsating, minimalist, electronic sound with a reach that would shape and influence music from synth to techno for decades to come.

There was nothing comparable to this debut release which is why so many rock critics failed to grasp what had just happened.

Now, over forty years on, Suicide’s debut album is set to be re-released by Mute/BMG as part of their Art of the Album series.

In an exclusive interview with Dangerous Minds, Martin Rev discusses his life and work and the making of one of music’s greatest albums

Tell me about your childhood, what it was like, and what were your first musical influences?

Martin Rev: I think I was a fairly happy child as far as possible, you know, with all the ups and downs. I was very lucky to have the family I did. We all played music as it turned out, non-professionally. My brother played, was given lessons. My father played. My mother played, she had lessons as a young girl so she played in the home. They wanted their kids to definitely learn music. My father was one of the most distinctively talented musicians I’ve ever heard in my whole life. He played song after song on a guitar or a mandolin. Never read or studied a note. He was incredible that way. So, it was a musical family. That added to the richness of my childhood.

Otherwise, it was all the usual growing pains and doubts and dreams. It was a fairly lucky period to grow up in between war kind of thing. After World War Two and before Vietnam. America had probably reached its pinnacle of affluence. That whole generation for a while, well, a couple of generations, felt an incredible sense of future potential that anything could happen or be done and the whole future was wide open with possibilities.

A little different than it is now. There wasn’t the pessimism or the awareness of the dark clouds behind the covers as there is now. There was an optimism—even though I didn’t buy all that the country was selling even as a kid. I was a bit of radical rebel already as a teenager. But there’s no complaints there, it was what it was. I was lucky to be given room and the opportunity to discover music which was something I could be thankful for, you know, every day of many lives because there’s nothing else I’d better do.

I grew up hearing all the great songs coming off the radio as a kid. I was bitten, smitten by them as so many kids my age were. The golden era of rhythm and blues, American rock ‘n’ roll. There was all the rhythm and blues groups at the time, there was the Paragons, the Gestures, Little Richard, Mellow Kings, Danny and the Juniors, the Silhouettes. I mean you can go on and on but a lot of them had only one great song and a few of them had many—the Flamingos, the Students, these were the groups that were really happening. That was the music of the times. That’s what did it.

Were you buying records at this time?

MR: There was 45s. There really wasn’t the album, there wasn’t FM radio. The price of a 45 then was 45c to a dollar. You could buy them easily and some people kinda got into collecting them so when there were parties, things like this, in people’s basements, there was always a couple of people there who had great collections who would be the ones who would spin the records all night.

When did you first consider the possibility of a career in music?

MR: I got serious about music about ten or eleven. At eleven I started figuring out the songs I was hearing on the radio on piano. I started improvising around that time or soon after like boogie-woogie and improvising towards jazz. I think about by twelve, I was pretty much set on making music my life. That’s the way I felt then and still do.

I just wanted to play and make music. I just saw myself as playing live. I envisioned it as a beautiful way to play in clubs and meet girls. That’s a typical thing when you’re twelve or thirteen. The vision of coming off a bandstand in a nightclub and how attractive that could be to girls. I guess the idea of whoever I have evolved into as an artist took shape and form over the years after that but I guess it was all there innately at that time. I just wanted to play, everything around me was great and exciting to me—rhythmically, vocally. I started hearing jazz a couple of years later and I just wanted to learn how to play that stuff and play in bands. I didn’t think much of recording until a little later.

When I was about fifteen, I started playing in little rhythm and blues groups doing one-nighters and things like that. Musically it was ecstatic. The agony and the ecstasy. The agony, it wasn’t difficult except in the economic sense. It was just finding a way to make ends meet and have the time to be free to make music which meant everything

What happened next, how did you meet Alan Vega, and when did you decide to form Suicide?

MR: I left home when I was eighteen. I was married with kids when I was twenty. I met Alan soon after that when I was about twenty-one or twenty-two. I was still very much totally involved in my own artistic evolution, you might say, as Alan was as a visual artist. We were totally dedicated which we both had in common. No risk factor at all. No future factor but to just evolve and create in our fields.

Alan had decided soon before I met him that he had to perform as a visual artist. That was after seeing Iggy Pop and the Stooges play in New York for the first time.

I had my own group called Reverend B when I met Alan. I was doing certain shows in the city. It was a very avant garde, free improvisational group that used electronic keyboard ‘cause that was the only thing available. You had to borrow it, there weren’t a lot of other keyboards in the venues we played.

Alan was working, well, not working but living, he was given the keys to the Museum of Living Artists which was a large loft that was designated for a co-op gallery of artists who did shows on a co-op basis like every month or two. He had the keys to that and that’s where we met. Because both of us were so much in that same place of total dedication. We were the only ones left there at night and talking and playing and thinking about art and music and trying to survive. We were the last ships in the night, so to speak, and we started thinking about putting something together.

Alan at that time was at a crossroads in his life because he was living with friends and he’d just separated from his wife of several years and he didn’t have a place to live either so he was living in the Museum itself. We were both pretty much in that same place and that space was keeping us off the streets. Although I was a little better advantaged at that point because I had a place to go but it was a good travel. Once I would get on the train and go up there that was the end of the night.

How did you come up with Suicide’s powerful distinctive sound?

MR: I think some of it is visceral, it’s just something that’s part of your fingerprint that is given to you by nature the way you approach music.

When I think back, if I was doing a show as a teenager in a jazz band say, as soon I saw the certain facility, it could be any kind of band, I played with a certain kind of an energy and certain kind of commitment. I always did.

Also, as an early teenager I started working in these resorts in the summer playing dancing—older people dancing—square stuff, but the way I played it was like they’d dance like crazy and they’d come over to the bandstand and say, “What the hell was that?” They were going around in circles the way I saw it. And that was kind of the way I am, the way I approach music, my energy. I am involved when I am inside music.

As far as Suicide for me was to work with the potential of electronics in terms of performance. Putting devices together, combining them, I mean really cheap, small inexpensive stuff. But I heard the potential. I heard what that was in terms of a total open frontier and that was a direction and everything I was going into that direction created a certain energy and then rediscovering my roots which was rock ‘n’ roll which was so innate because I was born into it before—it wasn’t something I could analyze it was just the music of of my time as a child. Coming back to that essential force or energy that made it work for me then and still did when I listened to certain things that appealed to me. One can analyze as a certain basic energy and rhythm which is the driving force that made rock work for us. Little Richard a perfect example of many. But able to do that now in a way that was totally fresh to me. Exciting because to me it wasn’t repeating what was done, it was finding a new way to express something that universal energy and drive.

I guess I was printed with a lot of that energy maybe from rock ‘n’ roll too and something who knows maybe ancestral, familial.

What were Suicide’s first gigs like?

MR: I think our first show was at the Museum of Living Artists, if I’m not mistaken. I was playing drums. There was three of us. I don’t think there were that many people there, enough to play the gig.

Alan said after that first Museum gig let’s go to the Ivan Karp OK Harris Gallery. Alan actually had very unexpectedly landed a room to show his sculptures in a group show by Ivan Karp. This was one of the really major galleries of the day, now downtown in Soho.

We always thought where can we go next to get a gig where nobody knows us and there’s very few places to play. Now a lot of the clubs from the sixties were closing, the whole scene is closing down, otherwise they’re too big like the Fillmore, they’re never gonna put us in. By 70-71, it began to feel like a transition as well. The sixties had kinda tapered off. The whole period of Haight-Ashbury, St. Mark’s Place, that was so incredibly vibrant in the sixties, was now starting to fade a bit like any other movement or form of thought. You had kind of a limbo period. Of course, I didn’t register all of that in detail, I was too involved in just me and my life and not that economically, theoretically safe anyway at that point. It was still a vibrant city to me.

Suicide: Alan Vega and Martin Rev.

More from Martin Rev and Suicide, after the jump…