In 1922, T. S. Eliot’s poem The Wasteland was published in the Criterion magazine. It was read by no more than a handful of people. The poem was then republished in book form in a limited edition of 450 copies. Within a decade, The Wasteland was considered one of the greatest poems of the twentieth century and its modernist influence continues to this day.

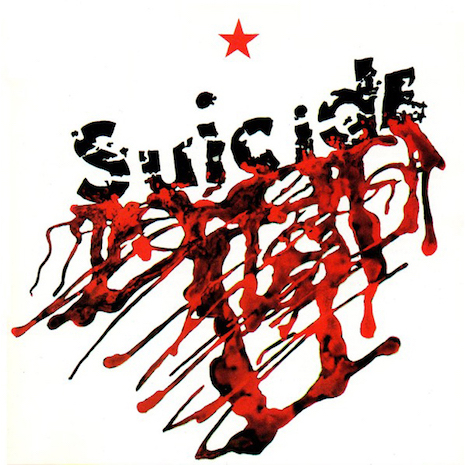

In December 1977, the sound of the future arrived when a two-piece band called Suicide released their self-titled debut album to little acknowledgement or fanfare except from a few astute record critics in England. The American press mostly reviled it. Record buyers ignored it. Yet, within a decade, Suicide was considered one of the most important and influential album releases of all time.

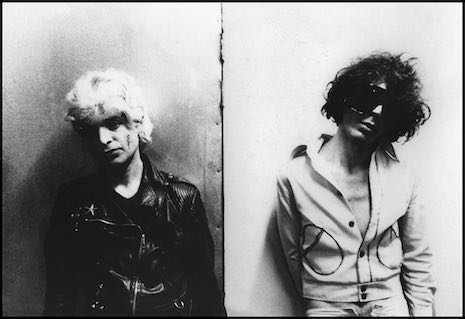

Suicide consisted of Martin Rev (keyboards) and Alan Vega (vocals). This thirty-something musical pairing of radical mavericks stripped down rock ‘n’ roll into its constituent parts and reinvented it as a new, pulsating, minimalist, electronic sound with a reach that would shape and influence music from synth to techno for decades to come.

There was nothing comparable to this debut release which is why so many rock critics failed to grasp what had just happened.

Now, over forty years on, Suicide’s debut album is set to be re-released by Mute/BMG as part of their Art of the Album series.

In an exclusive interview with Dangerous Minds, Martin Rev discusses his life and work and the making of one of music’s greatest albums

Tell me about your childhood, what it was like, and what were your first musical influences?

Martin Rev: I think I was a fairly happy child as far as possible, you know, with all the ups and downs. I was very lucky to have the family I did. We all played music as it turned out, non-professionally. My brother played, was given lessons. My father played. My mother played, she had lessons as a young girl so she played in the home. They wanted their kids to definitely learn music. My father was one of the most distinctively talented musicians I’ve ever heard in my whole life. He played song after song on a guitar or a mandolin. Never read or studied a note. He was incredible that way. So, it was a musical family. That added to the richness of my childhood.

Otherwise, it was all the usual growing pains and doubts and dreams. It was a fairly lucky period to grow up in between war kind of thing. After World War Two and before Vietnam. America had probably reached its pinnacle of affluence. That whole generation for a while, well, a couple of generations, felt an incredible sense of future potential that anything could happen or be done and the whole future was wide open with possibilities.

A little different than it is now. There wasn’t the pessimism or the awareness of the dark clouds behind the covers as there is now. There was an optimism—even though I didn’t buy all that the country was selling even as a kid. I was a bit of radical rebel already as a teenager. But there’s no complaints there, it was what it was. I was lucky to be given room and the opportunity to discover music which was something I could be thankful for, you know, every day of many lives because there’s nothing else I’d better do.

I grew up hearing all the great songs coming off the radio as a kid. I was bitten, smitten by them as so many kids my age were. The golden era of rhythm and blues, American rock ‘n’ roll. There was all the rhythm and blues groups at the time, there was the Paragons, the Gestures, Little Richard, Mellow Kings, Danny and the Juniors, the Silhouettes. I mean you can go on and on but a lot of them had only one great song and a few of them had many—the Flamingos, the Students, these were the groups that were really happening. That was the music of the times. That’s what did it.

Were you buying records at this time?

MR: There was 45s. There really wasn’t the album, there wasn’t FM radio. The price of a 45 then was 45c to a dollar. You could buy them easily and some people kinda got into collecting them so when there were parties, things like this, in people’s basements, there was always a couple of people there who had great collections who would be the ones who would spin the records all night.

When did you first consider the possibility of a career in music?

MR: I got serious about music about ten or eleven. At eleven I started figuring out the songs I was hearing on the radio on piano. I started improvising around that time or soon after like boogie-woogie and improvising towards jazz. I think about by twelve, I was pretty much set on making music my life. That’s the way I felt then and still do.

I just wanted to play and make music. I just saw myself as playing live. I envisioned it as a beautiful way to play in clubs and meet girls. That’s a typical thing when you’re twelve or thirteen. The vision of coming off a bandstand in a nightclub and how attractive that could be to girls. I guess the idea of whoever I have evolved into as an artist took shape and form over the years after that but I guess it was all there innately at that time. I just wanted to play, everything around me was great and exciting to me—rhythmically, vocally. I started hearing jazz a couple of years later and I just wanted to learn how to play that stuff and play in bands. I didn’t think much of recording until a little later.

When I was about fifteen, I started playing in little rhythm and blues groups doing one-nighters and things like that. Musically it was ecstatic. The agony and the ecstasy. The agony, it wasn’t difficult except in the economic sense. It was just finding a way to make ends meet and have the time to be free to make music which meant everything

What happened next, how did you meet Alan Vega, and when did you decide to form Suicide?

MR: I left home when I was eighteen. I was married with kids when I was twenty. I met Alan soon after that when I was about twenty-one or twenty-two. I was still very much totally involved in my own artistic evolution, you might say, as Alan was as a visual artist. We were totally dedicated which we both had in common. No risk factor at all. No future factor but to just evolve and create in our fields.

Alan had decided soon before I met him that he had to perform as a visual artist. That was after seeing Iggy Pop and the Stooges play in New York for the first time.

I had my own group called Reverend B when I met Alan. I was doing certain shows in the city. It was a very avant garde, free improvisational group that used electronic keyboard ‘cause that was the only thing available. You had to borrow it, there weren’t a lot of other keyboards in the venues we played.

Alan was working, well, not working but living, he was given the keys to the Museum of Living Artists which was a large loft that was designated for a co-op gallery of artists who did shows on a co-op basis like every month or two. He had the keys to that and that’s where we met. Because both of us were so much in that same place of total dedication. We were the only ones left there at night and talking and playing and thinking about art and music and trying to survive. We were the last ships in the night, so to speak, and we started thinking about putting something together.

Alan at that time was at a crossroads in his life because he was living with friends and he’d just separated from his wife of several years and he didn’t have a place to live either so he was living in the Museum itself. We were both pretty much in that same place and that space was keeping us off the streets. Although I was a little better advantaged at that point because I had a place to go but it was a good travel. Once I would get on the train and go up there that was the end of the night.

How did you come up with Suicide’s powerful distinctive sound?

MR: I think some of it is visceral, it’s just something that’s part of your fingerprint that is given to you by nature the way you approach music.

When I think back, if I was doing a show as a teenager in a jazz band say, as soon I saw the certain facility, it could be any kind of band, I played with a certain kind of an energy and certain kind of commitment. I always did.

Also, as an early teenager I started working in these resorts in the summer playing dancing—older people dancing—square stuff, but the way I played it was like they’d dance like crazy and they’d come over to the bandstand and say, “What the hell was that?” They were going around in circles the way I saw it. And that was kind of the way I am, the way I approach music, my energy. I am involved when I am inside music.

As far as Suicide for me was to work with the potential of electronics in terms of performance. Putting devices together, combining them, I mean really cheap, small inexpensive stuff. But I heard the potential. I heard what that was in terms of a total open frontier and that was a direction and everything I was going into that direction created a certain energy and then rediscovering my roots which was rock ‘n’ roll which was so innate because I was born into it before—it wasn’t something I could analyze it was just the music of of my time as a child. Coming back to that essential force or energy that made it work for me then and still did when I listened to certain things that appealed to me. One can analyze as a certain basic energy and rhythm which is the driving force that made rock work for us. Little Richard a perfect example of many. But able to do that now in a way that was totally fresh to me. Exciting because to me it wasn’t repeating what was done, it was finding a new way to express something that universal energy and drive.

I guess I was printed with a lot of that energy maybe from rock ‘n’ roll too and something who knows maybe ancestral, familial.

What were Suicide’s first gigs like?

MR: I think our first show was at the Museum of Living Artists, if I’m not mistaken. I was playing drums. There was three of us. I don’t think there were that many people there, enough to play the gig.

Alan said after that first Museum gig let’s go to the Ivan Karp OK Harris Gallery. Alan actually had very unexpectedly landed a room to show his sculptures in a group show by Ivan Karp. This was one of the really major galleries of the day, now downtown in Soho.

We always thought where can we go next to get a gig where nobody knows us and there’s very few places to play. Now a lot of the clubs from the sixties were closing, the whole scene is closing down, otherwise they’re too big like the Fillmore, they’re never gonna put us in. By 70-71, it began to feel like a transition as well. The sixties had kinda tapered off. The whole period of Haight-Ashbury, St. Mark’s Place, that was so incredibly vibrant in the sixties, was now starting to fade a bit like any other movement or form of thought. You had kind of a limbo period. Of course, I didn’t register all of that in detail, I was too involved in just me and my life and not that economically, theoretically safe anyway at that point. It was still a vibrant city to me.

Suicide: Alan Vega and Martin Rev.

What was the response to your performances? Was it antagonistic?

MR: I think there was more shock at that time. We did have a bit of riot at the second Museum show because there was a contingent of people like us—revolutionary South American group that had come in to visit and they wanted very much to hear us. At one point one of these guys broke out a trombone and started playing. Alan already being into audience involvement at that time went over and pulled the slide out the trombone while he was playing and that set-off like a firebomb a riot with throwing things all kinds of stuff.

The reactions started getting more and more diverse but more and more antagonistic as we started playing clubs, again, galleries weren’t so much, as I remember. The biggest, of course, was the confrontations and antagonisms which came when we first toured Europe with Elvis Costello and the Clash.

Suicide recorded a single which led to you getting signed for Red Star Records, can you talk about that?

MR: We had been playing now for about five to six years, I would say, not steadily, of course, dealing with the limited access of clubs in general in that period and also ones that would let somebody totally new and unknown and so radical in. So whenever we would get a show, a few a year or whatever we would do, and at one point, I’d say around the beginning of ‘77, Marty Thau, who had quite a bit of success working for Buddha Kama-Sutra after he got out of school he was hired by them as promotion man and promoted a lot of hit records, a lot of gold records, lived very well. Then he decided to leave the whole record industry and become an independent and search groups in venues, which most of his peers never got that far down to the streets. He would bring groups into labels as an independent which he did with Blondie—he was involved early on with the Ramones—his track record is extensive.

He knew of us. When he’s interviewed he says he thought we could never make a record and never thought about involving himself with us. A couple of years later, we had put a single on Max’s jukebox. Marty apparently heard it one night having dinner in Max’s and he asked “Who’s this?” (It was “Rocket USA” on the jukebox.) He asked somebody who it is and they said “Suicide.” And he says, “Wow! Suicide. I never thought they could make a record like this.” It was so far out, so confrontational, and the next thing he calls us and we had just come back from a gig in Boston, a club called The Rat, somebody drove us there and back. We got a call the next day down at Museum. Marty Thau was interested in meeting with us. That was maybe February, and we talked about doing this or that and he set up an audition here-and-there which was unsuccessful and we played for Mercury. He had signed the Dolls to Mercury, he had these connections. Then he got asked to start a label under another label called Prelude Records. They were veteran music industry people, two partners, who were now hearing about this new scene in New York and they wanted to tap into it and were advised to get Marty Thau because he was down into it and knows who to bring in. They called him, proposed they’d set up a label for him in their offices so they can have access and he will bring in these new acts. They knew nothing about it except it was happening. Now, we’re talking about ‘77.

So, you got a deal, you’re on Marty Thau’s Red Star Records, did you record the first album in order of its tracks, just like a live album?

MR: Yeah, I think so. Actually, it was in that order. The order may have been changed a little bit after but I’m not sure about that but probably it was that order. We had been playing those tracks just about every one for several years and some more recently maybe whenever we played or rehearsed, so it was a live record.

Can you tell me about your writing process with Alan, did the music come first?

MR: I’d come in and start playing an idea. We just start playing in the very early days and it was kind of a wall of sound the way it was perceived but Alan had lyrics that he would just improvise or had been writing on his own and had decided to throw in things he had already, you know, been sketching down on scraps of paper. Basically he started out screaming for the most part and everything was very much like a free, incredibly thick wall of sound but with different sections because he would use certain lyrics with titles for each one but I don’t know if anybody else could discern the difference even with the titles to those sections. It was totally wall of sound with electronic kind of stuff and that was now getting carved out into tangible tracks.

You used to go and practice at a university, was that where you started writing songs?

MR: I used to go in there to practice in those days. It was a few blocks from Museum. I was downtown and in those days you could just walk in, take the elevator up to the seventh floor, or whatever it was, where they had all these various practice rooms and classrooms with grand pianos, and it was all empty because classes were finished but the floor was open. Security was such in those days that I just tried it one day and there it was. I even brought musicians I knew up there a couple of times and we had a session or two, improvisational sessions, and I sometimes used the grands in the practice rooms.

One day, I went up there looking for something that would even take us further, allow more of a vocal involvement where Alan was concerned and I found “Rocket USA” right away like in three minutes. It opened up a whole territory from there because I knew that was it—that was the direction. I brought it back to a little electronic sound and started just doing more of those after that and it was something that Alan fitted into very well as opposed to fitting into more abstract improvisational things.

What about ‘Ghost Rider’?

MR: The same way. That was probably the second one I made.

I probably came out of that soundproof practice room with a couple of things. “Ghost Rider” was one of the them. “Cheree” was probably the third.

And ‘Johnny’?

MR: “Johnny” came about the same way soon after. Once I opened up that territory which was fresh and visual for me. It harkened back to something very innate in my childhood. Something very American in terms of imagery, fantasy, rock ‘n’ roll.

“Johnny” was like the first track I played as a boogie-woogie. It’s like a boogie-woogie line. There’s not much difference between early jazz and rock ‘n’ roll and boogie-woogie, you know. I can hear Little Richard play boogie-woogie or Jerry Lee Lewis. It’s all related.

What do you mean by it was ‘visual for you’?

MR: I was seeing it. I was seeing…when I was a child, now we’re talking maybe five or six, I had some in my room, which I shared, some paintings, children’s wooden, cut-out kinda things that had like the cow jumping over the moon and cowboys, you know, small, a foot-by-a-foot, on the walls. I grew up with cowboy movies and that whole visual fantasy aesthetic of the west—horses, cowboys and indians, that whole thing. As soon as I started playing “Rocket” I started seeing those pictures. I started seeing the west, the desert, the whole thing. It was totally my roots in a way although I’d never been out of New York but it was my psychological imprinted roots from TV and my generation.

The little-known “Frankie Teardrop” music video directed by Paul Dougherty

And the tracks ‘Girl,’ ‘Frankie Teardrop,’ and ‘Che’?

MR: The same way. Not at the same time.

They all came the same way. I already knew, I already felt there was this avenue opening up now where I could express things that moved me and everything that I loved, in a way, but in this new, fresh way, this simple way.

I had also grown up with Latin music very favorably. My friends and I as teenagers used to listen to Latin quite a bit just as much as jazz and rock. Salsa especially. And being, you know, on the streets of New York too it’s a very Latin place, it’s Hispanic, you know, Puerto Rican. New York is very much tinged from all its elements. Puerto Rican and Cuban and Hispanic elements are very prevalent in your neighborhoods and whatnot. Most of them, well, the ones I lived in.

So “Girl” that was like Latin-tinged, so was “Cheree” in a way. These were songs that were imprinted very early. You had like what the Coasters used to do, Latin-kinda things like “Down in Tijuana,” or the Drifters “Spanish Harlem.” I was just expressing all those sides of what always moved me but now it was fresh to me to do it this way. I wasn’t interested in reprinting those songs I’d already heard.

When Suicide’s first album came out at the end of 1977, what was the response from the music press?

MR: It was either total ignorance, feigned ignorance or real ignorance. Not listening to it, or ambivalence as in the case of America or very harsh reaction, negativity. More in the American reviews—Rolling Stone and whatnot. Pretty heavy backlash.

I really didn’t think about it much, I didn’t really care as much as one might think because I was involved in me—in my ecstasy, you might say, in my obsession which I’ve always been involved in which is to keep creating.

If I felt good about what I was doing and what the potential was, it minimises all the external stuff.

Interestingly enough, the European reviews, and especially the UK reviews—Sounds, NME—were very astute, surprisingly astute. I think it was Roy Hollingsworth reviewed a show of us, it would be our first review while we were still playing at Mercer Arts Center. He caught us by accident because that was a place where a lotta groups played and he wrote a review that said “What has rock wrought? What has rock created?” It was great review but he was talking about how he was totally taken back by how he walked into this theater and heard us.

I remember Sounds was so detailed in their analysis and where songs came from—they were talking about influences like certain standard songs and things from other worlds too like jazz. It was a surprise, a nice surprise ‘cause it was very positive.

The French press Liberation was apparently into us before we even recorded. But there was a lot of other reviews from other countries but Europe essentially was ahead of the mark as far as that was concerned. America was so, it still lags in a sense now but not to that extent, it was such a commercial marketplace then.

What do you think of that album now?

MR: Thankfully when I listen to it, which is certainly sporadically, I don’t need to hear what I’ve done regularly and that’s the same for my solo records, but when I hear it, it holds up. It’s definitely not like: “Oh, shit that’s terrible, that’s terrible, terrible, terrible, terrible, terrible, terrible. Change this, this, this this! How could I have done that?” No. That’s a fortunate thing for me. When you create something and it still works even though you can hear certain things you might do a little differently now, if you were to go in and re-edit it or this and that. Very few on the Suicide record. So, it’s okay. After that it’s in the world. It’s something I passed through—I did it.

Suicide was part of my development then. It’s considered major to some extent and that’s fine, but I am more where I’m going today. I was doing music before Suicide and I’m doing it after. But it’s good. The record definitely holds up which to me is the essential thing.

Suicide’s groundbreaking debut album is reissued on red vinyl, CD and digitally on July 12th, 2019 via Mute / BMG.

Martin Rev’s album ‘Demolition 9’ is out now, check his full catalog here.

Previously on Dangerous Minds:

Suicide: The band that will always sound like the future

Suicide’s Alan Vega interviewed by Gregg Foreman on ‘The Pharmacy’

‘Ghost Rider’: Amazing new video surfaces of Suicide, live in 1980