Tales of nature taking bloody revenge on humans have been a staple for writers and film-makers over the years. In cinema there have been mutated ants invading Los Angeles in the first monster bug movie Them! in 1954, cute rabbits leaving a trail of death and destruction in Night of the Lepus, and even amphibians taking monstrous revenge on a poisonous patriarch in Frogs. In the 1970s, growing fears of ecological disaster inspired a whole menagerie of animals gone bad.

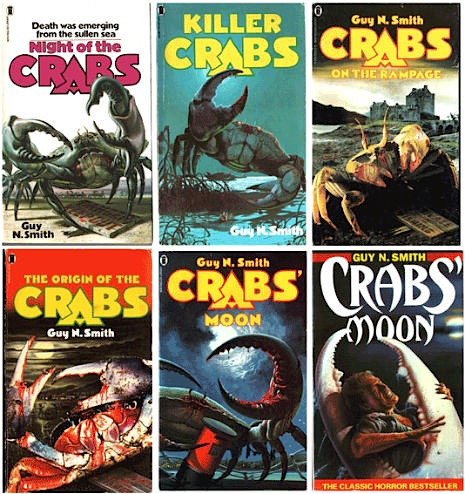

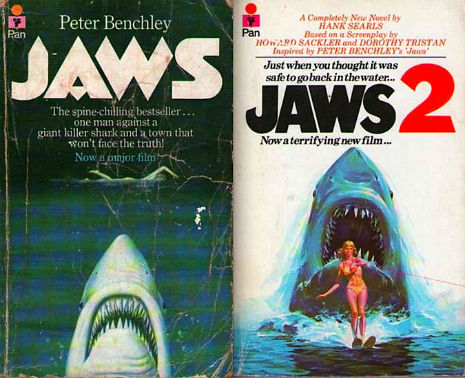

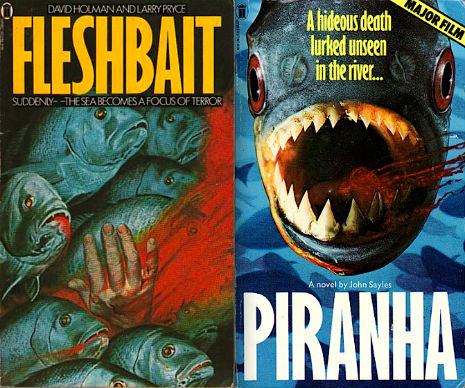

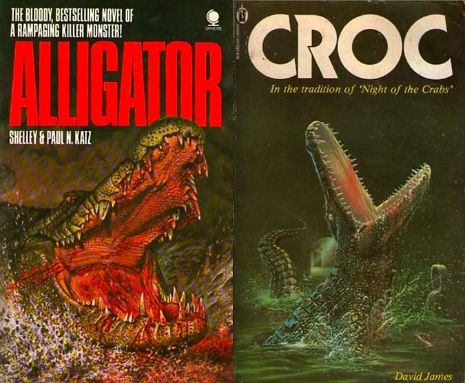

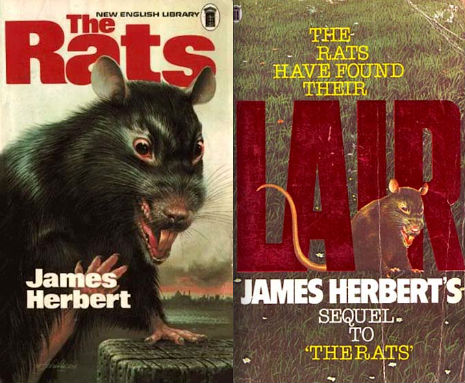

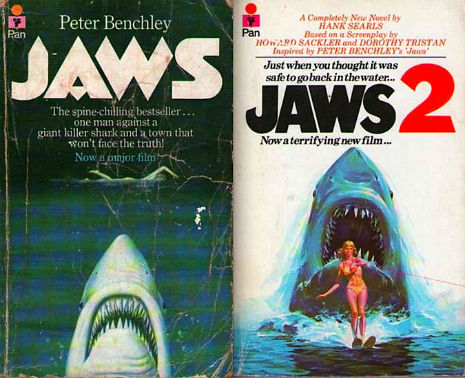

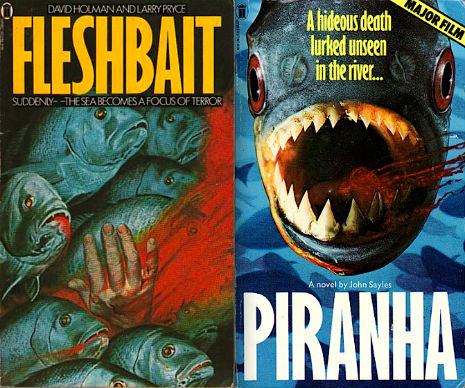

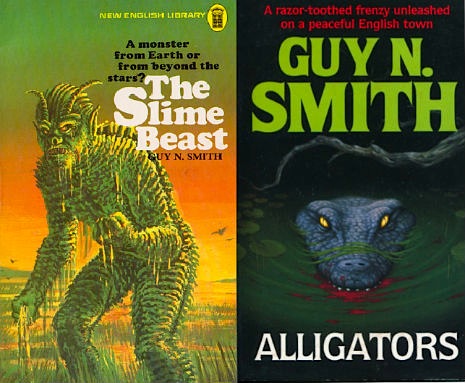

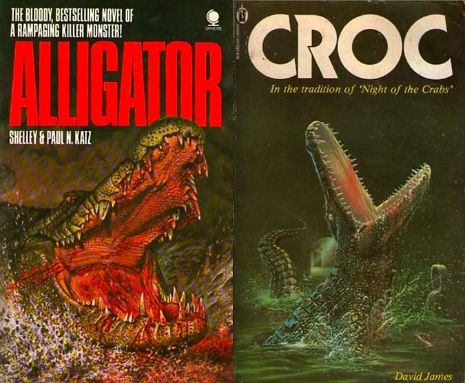

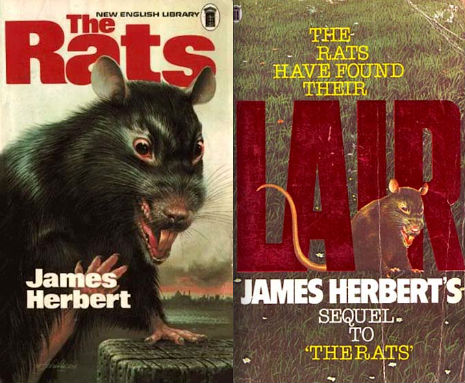

These fictions usually featured nerdy heroes taking on swarms of bees, plagues of rats, or shoals of man-eating fish, and often had an underlying critique of poverty caused by an indifferent consumerist society, as in James Herbert’s The Rats, or the political corruption of a small town as in Peter Benchley’s Jaws. Herbert’s Rats offered a template for Guy N. Smith’s The Night of the Crabs, Richard Lewis’s Devil’s Coach Horse, and Shaun Hutson’s Slugs. While Benchley and Spielberg’s great white shark saw John Sayles’ Piranha (novelization by Leo Callan), Dino De Laurentiis’s Orca, novelization by Arthur Herzog, “author of The Swarm” and the lesser Croc—a giant hungry reptile terrorizing New York’s sewer system “in the tradition of Night of the Crabs ” as the blurb reads—by David James.

Croc being tagged with Smith’s Night of the Crabs is just some lazy PR-man looking for a quick buck. Croc is about a pet reptile, which grows too big and is flushed down the lavatory. Somehow it survives living-off human refuse and the occasional down-and-out, and slowly grows to incredible size. When sewage workers Peter Boggs and Marian Fascetti investigate a blocked sewer, our story really begins. There’s a sub-plot about Mafia connections, but the main thrust is the politicians don’t want to know there’s a crocodile on the loose under New York City. And yes, there’s the team-up where Boggs is helped by policeman Glen Stapleton, who goes up against the beast.

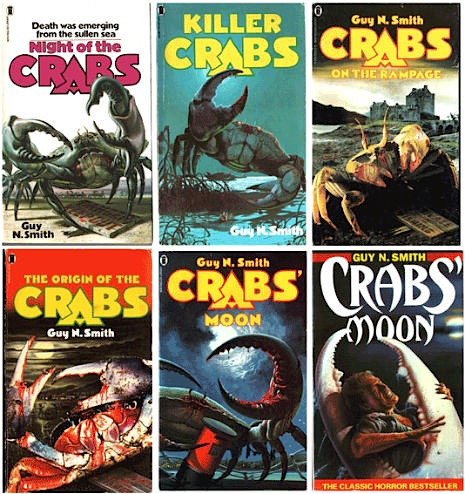

Smith’s Crabs has monster-sized crabs (up to sixteen feet across, if memory serves, with shels that can withstand armor-piercing missiles—the possible mutations of underwater nuclear testing), attacking the Welsh coastline. Like Herbert’s The Rats, Crabs’ mutant creatures have a taste for human flesh. This book spawned a series of six, finishing with Crabs Moon-The Human Sacrifice.

Of course, we can trace giant creatures back to fairy tales and writers like H. G. Wells, whose Food of the Gods had an idle couple of hired hands accidentally introducing the growth chemical “Herakleophorbia IV” into the food chain leading to giant chickens, wasps, rats and eventually human mutations. Wells also wrote the short story Empire of the Ants which featured a plague of giant ants attacking villages in the Upper Amazon, which foreshadows Them!.

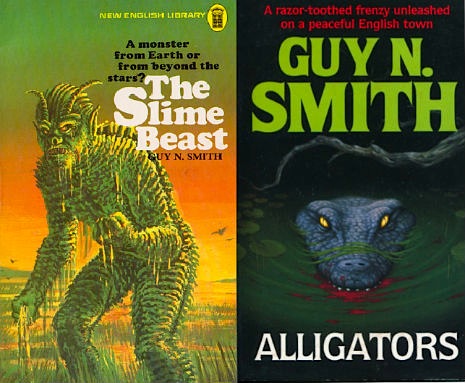

Wells undoubtedly had an major influence, but the rapacious insects of seventies pulp horror tended to be average size, and were only marked by their lust for human flesh. These insects were usually the by-product of scientific meddling or pesticides. Richard Lewis churned out a half-dozen of such books most notably Spiders and Devil’s Coach Horse, in which mutated earwigs devastate southern England. Guy N. Smith produced the insect horror of all horrors with Abomination in 1987, where pesticide causes every insect, worm, slug etc attack man. Smith more than any other author produced several “Nature Gone Bad” books with Snakes, Alligators, Locusts, the rather enjoyable Slime Beast, which may have come from another world, or may have been an evolutionary mutation created by man-made poisons, and The Throwback, where evolution goes wild.

The structure of these books is usually the same. The opening has some poor unfortunate, often a down-and-out or a lonely alcoholic, sometimes a misguided scientist, as first victim. Their body goes undiscovered allowing the rats, slugs, crabs, spiders, etc. to go unnoticed. There usually follows a series of tableaux where couples making out, small children and mothers, sad loners, and ambitious yuppies are killed with ever increasing violence. This leads to our hero, often a teacher (Herbert), a pipe smoking expert (Smith), or a disgruntled government employee (Hutson), who notes the pattern of deaths, the tell-tale markings or slime trails, and commences the creatures’ downfall.

Like Benchley’s Jaws, which was inspired by the Jersey Shore shark attacks of 1916, where four died and seven were injured, Arthur Herzog’s The Swarm was inspired by killer bee attacks in Africa, which he then transposed to South America and then the States. Herzog wrote the novelization of the vengeful killer whale film Orca. Herzog was an interetsing writer, his second book Earthsound tapped into shifting tectonics that meant earthquakes began to devastate the east coast of America. Herbert’s The Rats was also inspired by the author’s memories of post-war London infested by the vermin.

These books maybe poorly written, with often plodding lumpen prose, but they are incredibly addictive. I swallowed my way trough handfuls of these at a time during childhood, often reading two-a-day, and firmly believe such pulp fiction should be encouraged in school to help reluctant students read and get into the habit of books.

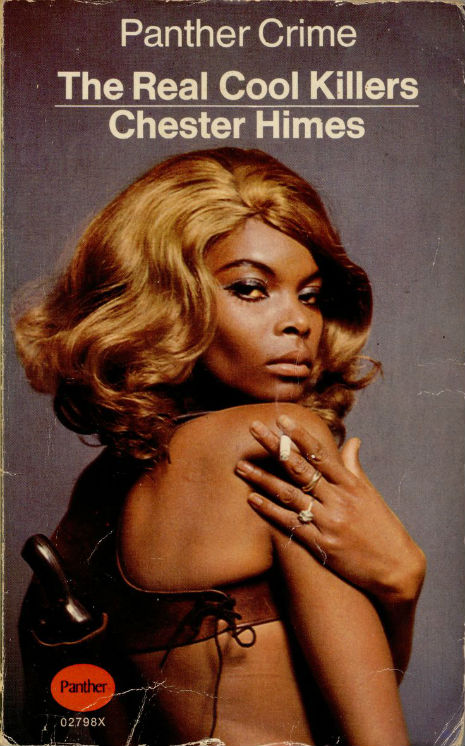

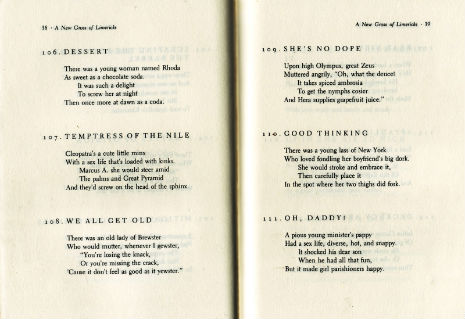

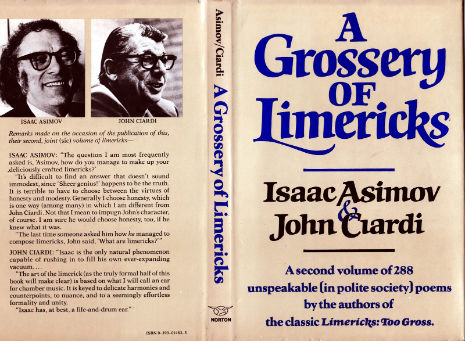

The flip-side to the rise to the disaster eco-horror in the 1970s was the comparable popularity of pulp sex books, whether Emmanuele, Xaviera Hollander’s The Happy Hooker or Timothy Lea’s (a pseudonym for screenwriter Christopher Wood) Confessions… series, which began with Confessions of a Window Cleaner. As Freud suggested, it seems that sex and death are inextricably linked.

Via Strange Things Are Happening, Not Pulp Covers, Scary MF, Starlogged and The Black Glove.

More pulp creature fictions after the jump…