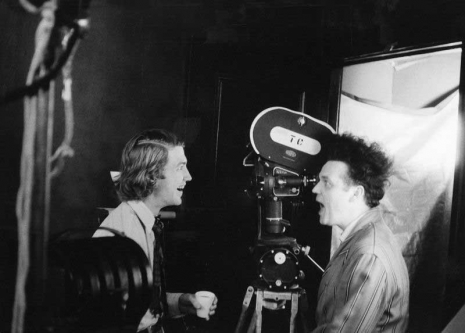

David Lynch and Jack Nance on the set of ‘Eraserhead’

I was reading a review of the new season of Twin Peaks in The New York Review of Books and came across an absolutely hilarious line about David Lynch I hadn’t seen before. The speaker is Mel Brooks, who (amazingly) hired Lynch to direct The Elephant Man on the strength of Eraserhead and an earlier short called The Grandmother. Brooks related that meeting Lynch in real life confounded his expectations: “I expected to meet a grotesque, a fat little German with fat stains running down his chin and just eating pork.” Instead he was confronted with a “clean American WASP kid ... like Jimmy Stewart thirty-five years ago.”

Looking for further context for the “fat little German” that never was caused me to go down a few Lynch wormholes dating back to the 1970s (the word wormhole is carefully chosen, because after all, this is also the man who directed Dune).

In their 1983 book Midnight Movies (which actually features Eraserhead as its cover image), J. Hoberman and Jonathan Rosenbaum include the following exchange:

Hoberman: I’ve never seen a scholarly article on Eraserhead, have you?

Rosenbaum: No. It’s funny–-it’s almost as if it’s too perfect. Maybe in order to have an academic cult film it also has to be unhinged. Except what we are calling “unhinged” and “cult,” they’re calling “classic texts.”

Perhaps it should not come as a surprise that an 88-minute industrial-surrealist art film that played a major role in catapulting its director in the ranks of internationally renowned directors was not tossed off as an afterthought. On the contrary: the movie took nearly five years to make, the director actually lived on the set of the movie, and through his force of belief in the project was able to inculcate an almost cult-like mystique among the stalwart crew, who were hardly getting paid anything.

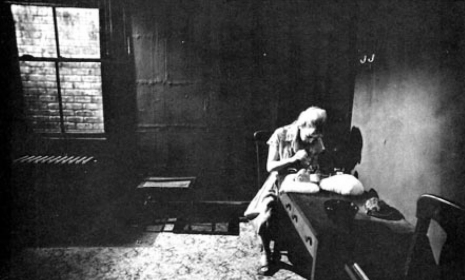

Lynch applies makeup on the face of Laurel Near, preparing to shoot a scene as the Lady in the Radiator

As fans of Lynch, we are very fortunate that a man named K. George Godwin attempted to document as much as he could about the making of Eraserhead before the coals had gotten too cold. In 1982 he published a detailed account of the years-long shoot called David Lynch and the Making of Eraserhead, which is available for you to read online. Most of the pictures in this post come from that book.

Sometime in the mid-1960s, Lynch, having informally studied art at the Corcoran School of Art in Washington, D.C., and thinking of himself fundamentally as a painter, made serious plans to visit Europe for three years. Remarkably, he instantly felt out of his element in Europe and broke off the trip after just 15 days. He returned home. Lynch has said of this experience, “I didn’t take to Europe. ... I was all the time thinking, ‘This is where I’m going to be painting.’ And there was no inspiration there at all for the kind of work I wanted to do.”

Lynch had submitted his short movie The Alphabet to the American Film Institute for a grant, where it had won distinction because it was so unlike the other movies in that year’s grouping—in a technical sense, they could not group it with the other entries. He ended up getting grant money for a short, which was to become The Grandmother. After The Grandmother Lynch tried to get a grant at a new AFI-affiliated organization called the Center for Advanced Film Studies. He submitted a script called Gardenback.

At the same moment, a producer at 20th Century Fox expressed interest in turning Gardenback into a feature-length movie, the prospect of which ended up creating problems because the AFI had recently gotten burned on a student feature-length project In Pursuit of Treasure and was reluctant to fund a student for anything similar. Interestingly, Lynch’s scripts tended to be on the short side because of his own instinctive understanding to allow nonverbal “scenes” to stretch on indefinitely. AFI looked at his script for Eraserhead, which was only 21 pages long, and concluded that the final movie would be 21 minutes. To his credit, Lynch told them that he expected it to be much longer. AFI agreed to fund a movie lasting 42 minutes, exactly double the original estimate. (As mentioned, the final product would run 88 minutes.) The funding for the movie amounted to $10,000. Actually, Frank Daniel, the dean of the AFI, threatened to resign if the funding for the movie were to be rejected. Obviously, he got his way.

In a scene cut from the movie, Henry, searching for a vaporizer to ease the suffering of the baby, opens a drawer and finds vanilla pudding and peas instead

Amazingly, the initial projections for the shoot were for a few weeks, approximately six weeks. The shoot ended up taking more than four years. The movie was shot on some disused stables that belonged to AFI, where Lynch also lived. Lynch’s close friend Jack Fisk, a well-regarded production designer and art director who met Sissy Spacek on the set of Badlands and married her soon after, appears in Eraserhead as the Man in the Planet. He and Spacek donated money to keep the movie afloat, as did Jack Nance’s wife Catherine Coulson, who was working as a waitress. Coulson, a production assistant on Eraserhead, many years later achieved fame as the Log Lady on Twin Peaks. For a while Lynch supported himself by delivering the Wall Street Journal, which paid $48.50 a week.

During the shoot, it can be fairly said that Lynch mesmerized his crew somewhat with his commitment to his artistic vision. Elmes tells of coming on board several months in because of the untimely death of the original director of photography, Herb Cardwell:

Everybody knew where everything was and what everything was and how David worked—what to do and what not to do. So I went into it the way I normally would, which is to, in a very quiet way, take charge of what needs to be done and to do it myself. In the case of Eraserhead I really had to do it myself because there was nobody else to tell to do it. We were doing a closeup of the baby and David had looked through the camera and lined it up and it was all ready to go. And I went over to the table and I moved this little prop over so that it was not hidden so much by something else. And Catherine turned to me and said, “Fred, we don’t move things on that table.” And I said, “Well, it’s just that it was blocked and I wanted to see it more clearly.” And she said, “Well, David has never moved anything on the table.” So I put it back. ... Heaven forbid David should see!

Lynch was rather alienated by the city of Philadelphia and considers the city to have had a definite impact on the end result. As Lynch said, “Eraserhead is the real Philadelphia Story. Philadelphia itself was a place I never wanted to go to – ever. It was really a frightening city. There’s an atmosphere in every place that you go. And it’s hard to imagine the atmosphere, but once you’re set in it, you say, ‘I see what you’re talking about.’” For him Philadelphia was “mainly an atmosphere of fear, just all-pervading fear.”

One of the most interesting revelations from Godwin’s book is a stray reference to a future project of Lynch’s that never ended up happening: “He already has another project lined up to follow Dune, a story of multiple murder called Red Dragon.” Remarkably, it seems that Lynch was at one time attached to Thomas Harris’ first Hannibal Lecter novel, which was filmed a few years later by Michael Mann as Manhunter. Jonathan Demme’s Oscar-winning The Silence of the Lambs was nearly a decade away. (In 2002 a second version of Red Dragon was released, this time directed by Brett Ratner, who has recently come under fire for multiple sexual assault accusations.)

My favorite bit in this extended interview with Lynch is a brief montage of moviegoers giving their instant appraisals of the movie. As you can imagine, some people really like it and some people really don’t!

Doreen Small, Charlotte Stewart, David Lynch, Catherine Coulson, and Herbert Cardwell

Lynch directs Charlotte Stewart and in the scene in which Henry arrives at the X household for dinner

Charlotte Stewart as Mary X rehearses the scene in which Henry arrives home and finds her having difficulty feeding the baby

After Henry cuts the bandages, the baby literally falls apart

Lynch, Nance, and the fake head of Henry, to be used in the decapitation scene.

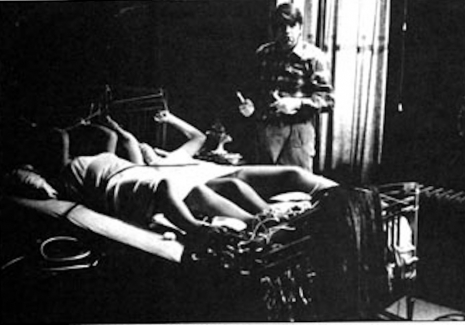

In a scene cut from the movie, Henry investigates a room down the hall and comes upon this complex situation with people trussed up in bed.