I attended a lot of funerals when I was a kid. A consequence of coming from a large extended Catholic family. My father was the eldest of nine children—he outlived them all. During my childhood, his brothers and sisters, and a few of their cousins and kin, died within a very short time of each other. My mother came from a small Protestant family. Her parents, uncles and aunts lived longer than my father’s kin, but when they died they fell within a year or two of each other.

At most of these funerals the body of the deceased was displayed in an open casket—either in a chapel of rest or at home where the family said decades of the rosary around the coffin. Seeing a corpse never seemed strange—death was part of life. The only thing that did seem odd was the strange almost pained expressions on the faces of the deceased. I put this down to their being embalmed—but never quite understood what this entailed or how the undertakers managed to keep the deceased’s eyes closed or their mouths shut.

When my beloved great aunt died, the undertaker left a few startling clues to the secret processes of making a corpse presentable.

Although she wore little make-up, someone had rendered her as an embarrassed spinster ashamed for causing such an unnecessary to-do. Her cheeks were flaming red, her lips fuchsia pink and her eyelids a cheapening smear of blue. This was a portrait of my great aunt by a Sunday painter overly influenced by Henri Matisse—it was garish and bright. Her eyes seemed wrong—flat and squint. I later found out eyelids are glued closed or covered with a flesh-colored plastic skin. Her mouth was pursed and I saw a telltale crimson thread with which her lips (her jaw) had been sewn or looped shut. Her hair was flat, as if she had been sleeping on her side. It wasn’t how my great aunt—ever meticulous and precise in her presentation—would have wanted to be remembered.

Embalming has been carried out by humans for some 5,000 to 6,000 years. The Egyptians made the greatest use of it—believing the preservation of a body somehow empowered the spirit after death. The brain and vital organs were scooped out and stored in jars. The interior of the corpse rubbed with herbs and preservatives before being wrapped in layers of linen cloth. Similar methods of embalming were carried out across Africa, Europe and China.

The modern methods of embalming developed as a result of discoveries made by the English physician William Harvey in the 1600s. Harvey determined the process of blood circulation by injecting fluids into corpses. Based on Harvey’s experimentation, two Scottish doctors William and John Hunter developed the process of embalming in the 1700s—offering their services to the public.

However, it was the slaughter caused during the American Civil War that led to embalming becoming popular with the public as families of soldiers killed on the battlefield wanted their loved ones’ bodies preserved for burial.

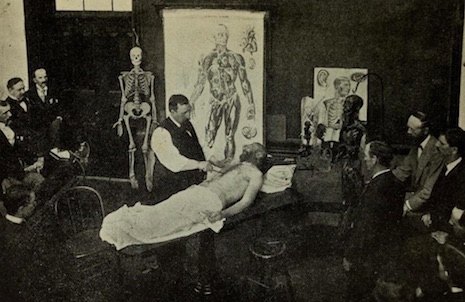

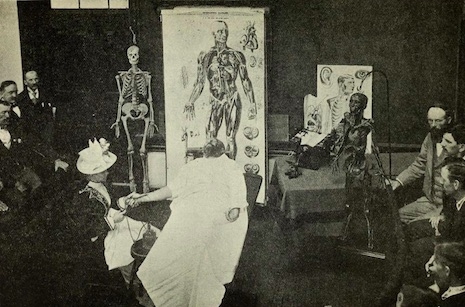

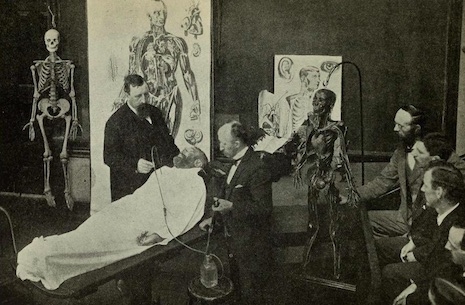

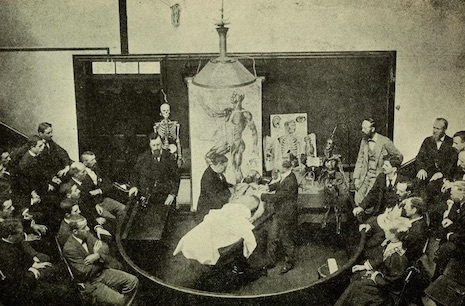

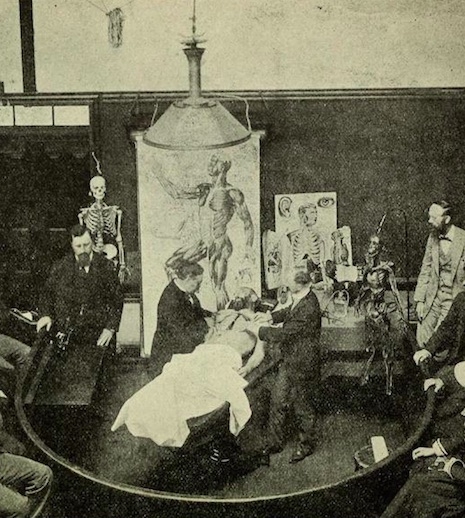

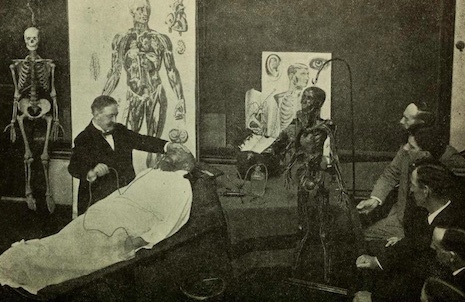

In 1897, Eliab Myers, M.D. and F. A. Sullivan wrote The Champion Text Book on Embalming. This book offered “Lecturers and Demonstrators in the Champion College of Embalming.” It was produced by the Champion Company from Springfield, Ohio, which manufactures equipment for use in embalming.

The Champion Text Book on Embalming gave the user a history of its subject and illustrated step-by-step guide to the process of successful embalming. From the draining of blood and bodily fluids to the dissection and removal of internal organs. The process explained in these atmospheric photographic plates is virtually the same as it is today.

Fig. 15 Raising the brachial artery.

Fig. 16 Injecting the arterial system through the radial artery.

Fig. 17 Aspirating blood from the heart.

Fig. 18 Making a dissection.

Fig. 18 Detail of making a dissection.

Fig. 19 Dissecting the Thoracic and Abdominal cavities.

Fig 19. Detail of dissecting the Thoracic and Abdominal cavities.

Fig. 20 Arterial injection by the eye process.

Fig. 21 Injecting arterial process by Champion needle.

Via the Public Domain Review.