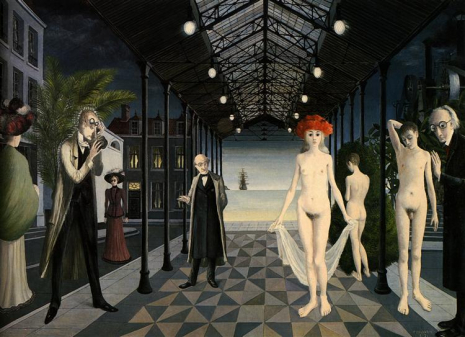

‘The Entombment’ (1957).

After being discouraged from pursuing a career in art by his lawyer father, Paul Delvaux would enroll at the Académie Royale des Beaux-Arts in Brussels. René Magritte, was studying there as well. Delvaux’s father unhappily agreed to his son’s study of architecture, though the younger Delvaux was deeply challenged by the evil that was mathematics, and failed his exam. Delvaux would then switch gears delving into the art of decorative painting. After an extended stay at the Académie Royale, he would graduate in 1924 after approximately eight-years of artistic immersion—though some sources indicate Delvaux would depart the school much later, in 1927. A quote attributed to Delvaux below nicely provides insight into his evolution as an artist and precisely what inspired him:

“Youthful impressions, fixed once and for all in the mind, influence you all your life.”

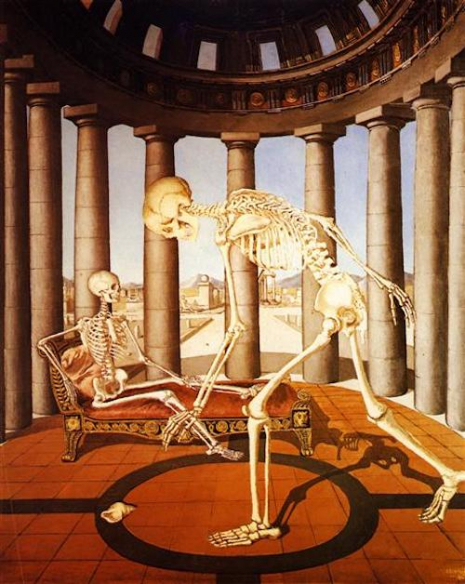

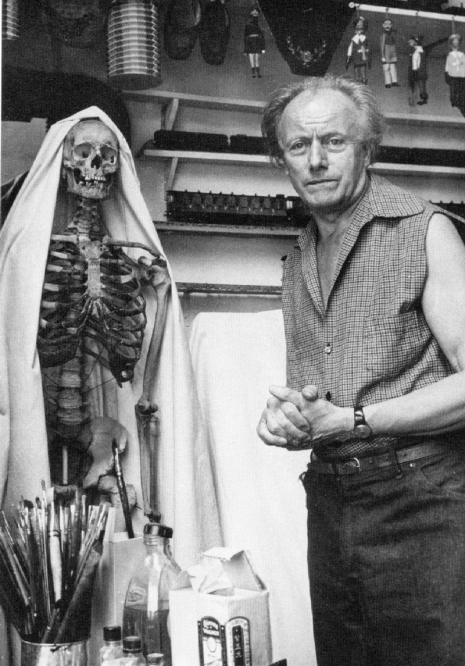

One of Delvaux’s artistic calling cards was his affinity for human skeletons. This interest could be traced back to his early schooling and his fascination with the skeletons that were on display in his biology classroom. Another account details Delvaux developed a fear of skeletons after being subjected to looking at one hanging in the music room at school. The artist had also been photographed numerous times at various ages with various skeletal muses. Also distinctly present in Delvaux’s dreamworld were entirely or partially nude women. Along with his skeletons, his paintings of women were often unsettling and confusing, as were some of the sexual situations Delvaux envisioned, then painted them into. Another young love of Delvaux was the illustrations of French illustrator Édouard Riou. Delvaux would become aware of Riou after receiving Jules Verne’s Journey to the Center of the Earth, which he got as a communion gift in 1907. Delvaux would be inspireded by artists affiliated with the Barbizon School, an art movement originating in the forest-town of Barbizon focused on the expert painting of landscapes, just south of Paris.

Furthermore, even though he had not completed his studies in architecture, the time he spent with the discipline would prove to be a strong influence in his work, especially those including another childhood love, trains, and train stations. In addition, during his time at Académie Royale, Delvaux was also under the direct tutelage of two Belgian painters; Constant Montald and the esoteric symbolist, Jean Delville. Traits of both Montald and Delville can be clearly seen in Delvaux’s work.

‘The Tunnel’ (1978).

A pivotal event in Delvaux’s career occurred in 1926 when he attended a gallery show for Giorgio de Chirico—the founder of the short-lived Scuola Metafisica (Metaphysical School) in Italy. De Chirico is credited for providing much of the fuel used to ignite the Surrealist movement. Surrealist works by René Magritte were of keen interest to Delvaux, as were Salvador Dali and Dada pioneer Max Ernst. Surrealism is quite evident in Delvaux’s paintings and concepts, but the artist did not consider himself a part of the movement. In fact, Delvaux’s work would be categorized in 1925 by German photographer, art historian and critic Franz Roh as “Magic Realism.” Another formative experience for the artist were his visits to the Musee Spitzner, which after burning down, turned into a traveling anatomical museum featuring approximately 250 different wax recreations of human anatomy, including hideous deformities and wax depictions of social diseases. In 1943, Delvaux would pay tribute to Pierre Spitzner in paint. Here’s Delvaux detailing his first visit to the Spitzner:

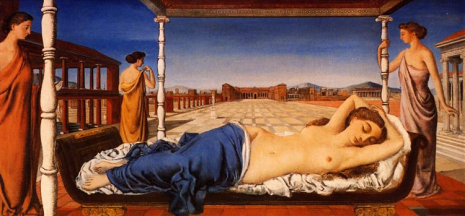

“In the middle of the entrance to the Museum was a woman who was the cashier, then on one side there was a man’s skeleton and the skeleton of a monkey, and on the other side, there was a representation of Siamese twins. And in the interior, one saw a rather dramatic and terrifying series of anatomical casts in wax, which represented the dramas and horrors of syphilis, the dramas, deformations. And all this in the midst of the artificial gaiety of the fair. The contrast was so striking that it made a powerful impression on me. All the ‘Sleeping Venuses’ that I have made, come from there. Even the one in London, at the Tate Gallery. It is an exact copy of the sleeping Venus in the Spitzner Museum, but with Greek temples or dressmaker’s dummies, and the like. It is different, certainly, but the underlying feeling is the same.”

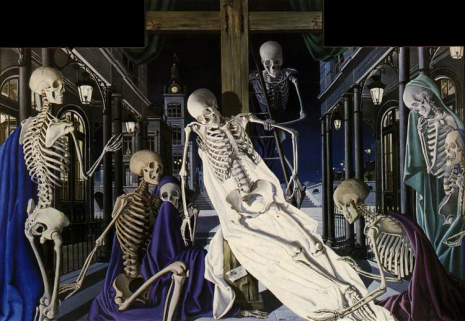

In 1933 Delvaux lost his mother. Following her death, he would destroy more than 100 of his early paintings after being criticized for the explicit nudity in his work. His father would pass away four years later. That year would bring about Delvaux’s first marriage to Suzanne Purnal, and the beginning of a new, horribly destructive chapter in Delvaux’s life. Unsurprisingly, in the decade he spent with a woman he never really loved who made his life miserable, Delvaux created some of his most masterful work. The Nazi occupation of Belgium would be yet another conduit for Delvaux’s creativity, bringing the artist to darker, more controversial places. He would paint as bombs descended across Brussels—most famously “Sleeping Venus” (1944). In 1948, priests were prohibited from attending one of his solo gallery shows, the reason more than likely his depictions of nude women. Men of the cloth would be banned from another show of Delvaux’s in Venice in 1954, this time at the behest of the future “people’s pope” Pope John XXIII, then-Cardinal Roncalli. Roncalli was incensed by Delvaux’s work and labeled it “heretical.” Here’s the painting by Delvaux that drove the future Pontiff over the edge:

‘Crucifixion,’ 1952. Delvaux would paint different versions of ‘Crucifixion’ and ‘Sleeping Venus’ over the course of his career.

Quite by chance during a visit to the Belgian seaside town of Saint Idesbald in 1947, Delvaux would meet up with his first love, Anne-Marie de Martelaere—a woman his family, especially his overprotective mother, had forced him to stop seeing. They rekindled their romance, and Delvaux would divorce Purnal and move to Saint Idesbald, marrying de Martelaere in 1952. The town is also home to the Paul Delvaux Foundation and Museum (founded in 1982). He would continue painting until he lost his sight in 1986 at the age of 89, the same year he lost the love of his life, Anne-Marie. Delvaux would move to Veurne, Belgium, where he would live the rest of his days before passing away at the age of 96.

Authentic paintings by Delvaux routinely sell at auction for well over a million dollars. In 2012 an oil on canvas by Delvaux “Le Canapé Bleu” (painted in 1967) sold for an astonishing $3,200,000.

Five decades of Delvaux’s divine NSFW work follows.

‘Woman in Cave’ (1936).

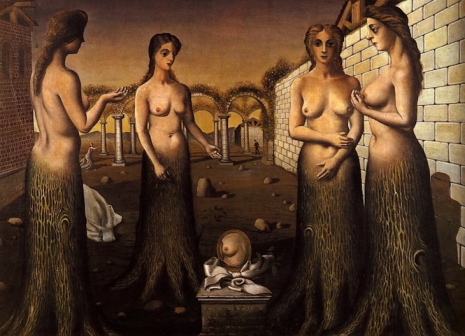

‘Women-Trees’ (1937).

‘The Joy of Life’ (1937).

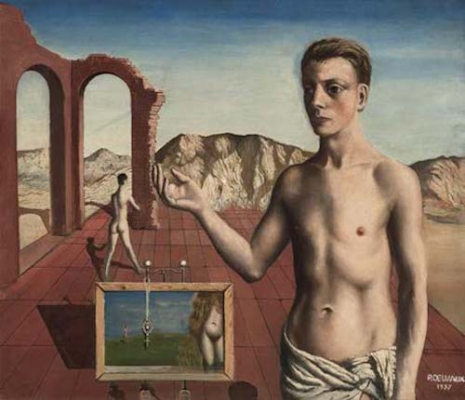

‘The Narrator’ (1937).

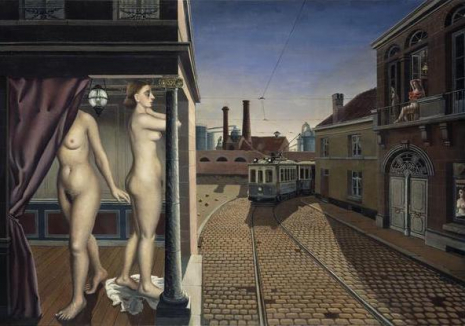

“Street of Trams” (1938).

‘The Call of the Night’ (1938).

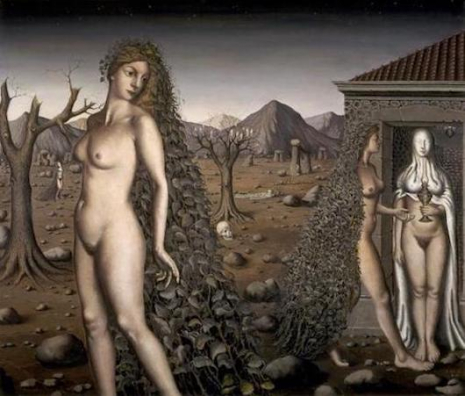

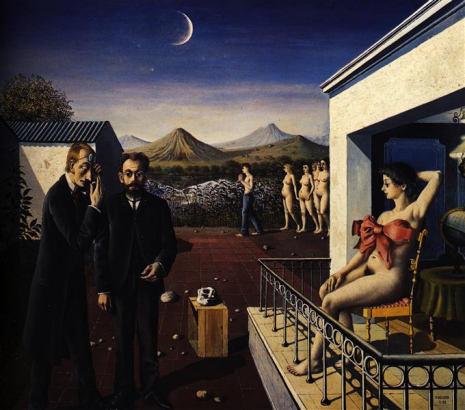

‘Phases of the Moon’ (1939).

‘The Village of the Sirens’ (1942).

‘The Sleeping Venus’ (1943).

‘The Musee Spitzner’ (1943).

‘The Skeleton Has the Shell’ (1944).

‘Call’ (1944).

“Echo Homo” (1949).

‘Crucifixion’ (1957).

‘Silent Night’ (1962).

‘The End of the World’ (1969).

‘A Tribute to Jules Verne’ (1971).

‘Sirens’ (1979).

Paul Delvaux and one of his skeleton muses.

Previously on Dangerous Minds:

Dream of Venus: Inside Salvador Dalí‘s spectacular & perverse Surrealist funhouse from 1939

Salvador Dali’s bizarre but sexy photoshoot for Playboy, 1973

Yves Tanguy: The master Surrealist who ate spiders and created smutty sketches just for fun

Monsters, death and the Mona Lisa stripping: Lorenzo Alessandri, father of Italian surrealism

Naughty nuns, Nosferatu and BDSM: Surreal works by the master of ‘anything goes’ Clovis Trouille