Once upon a time there was a little boy called Ingmar who lived with his father a clergyman and his mother a nurse in a snow-capped land in the north of Europe.

When he was five, Ingmar would hide under the dinner table and listen to his parents and their friends talk to each other as they ate their food. It was warm under the table and he dreamed about the conversations he overheard.

Having a pastor as a father taught Ingmar to look behind “the scenes of life and death.” He listened to his sermons and made the acquaintance of the devil. The devil was everywhere—“palpable and elusive”—in his father’s sermons and the fairy stories his mother read him a night, and “on the flowered wallpaper of the nursery.”

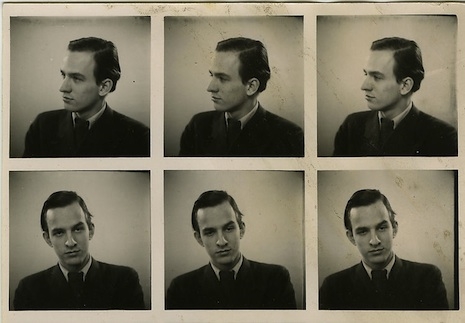

Ingmar was an imaginative little boy and he dreamt up adventure stories about his life to tell his friends. But his friends did not believe his stories and that hurt Ingmar. So, he withdrew from the world and kept his dreams to himself, only sometimes he would act out his stories with toys, and sometimes he would put them on in a little toy theater to amuse himself and his parents.

When Ingmar grew up he turned his memories of childhood into films, plays and stories.

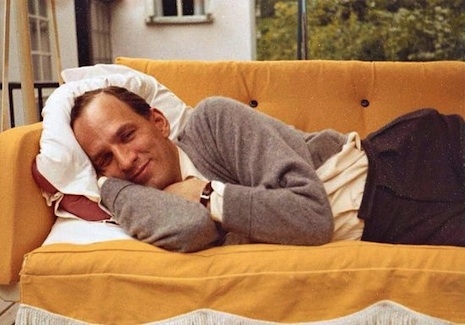

His memories of his childhood were important to Ingmar Bergman—he returned to them time-and-again in his movies and his writing. In his essay “What is ‘FilmMaking’” he wrote about a childhood incident—“the movement of a window-blind”—that gave him a sensation he wanted to recreate with his films:

It was a black window-blind of the most modern variety, which I could see, in my nursery, at dawn or at dusk, when everything becomes living and a bit frightening, when even the toys transform into things that are either hostile or simply indifferent and curious. At that moment the world would no longer be the everyday world with my mother present, but a vertiginous and silent solitude. It wasn’t that the blind moved; no shadow at all appeared on it. The forms were on the surface itself; they were neither little men, nor animals, nor heads, nor faces, but things for which no name exists! In the darkness, which was interrupted here and there by faint rays of light, these forms freed themselves from the blind and moved towards the green folding-screen or towards the bureau, with its pitcher of water. They were pitiless, impassive and terrifying; they disappeared only after it became completely dark or light, or when I fell asleep.

Bergman wanted to recreate this sensation of confronting something for which no name exists. When still a child, he soon realized this was something he could do with film.

The first film I ever owned was about ten feet long and brown. It pictured a young girl asleep in a prairie; she woke up, stretched, arose and, with outstretched arms, disappeared at the right side of the picture. That was all. Drawn on the box the film was kept in was a glowing picture with the words, ‘Frau Holle’. Nobody around me knew who Frau Holle was, but that didn’t matter; the film was quite successful, and we showed it every evening until it got torn so badly we couldn’t repair it.

This shaky bit of cinema was my first sorcerer’s bag, and, in fact, it was pretty strange. It was a mechanical plaything; the people and things never changed, and I have often wondered what could have fascinated me so much and what, even today, still fascinates me in exactly the same way. This thought comes to me sometimes in the studio, or in the semi-darkness of the editing room, where I am holding the tiny picture before my eyes and while the film is passing through my hands; or else during the fantastic childbirth that takes place during the recomposition as the finished film slowly finds its own face. I can’t help thinking that I am working with an instrument so refined that, with it, it would be possible for us to illuminate the human soul with an infinitely more vivid light, to unmask it even more brutally and to annex to our field of knowledge new domains of reality. Perhaps we would even discover a crack that would allow us to penetrate into the chiaroscuro of surreality, to tell the tales in a new and overwhelming manner. T the risk of affirming once more something I cannot prove, let me say that, the way I see it, we film makers utilize only a minute part of a frightening power—we are moving only the little finger of a giant, a giant who is far from not being dangerous.

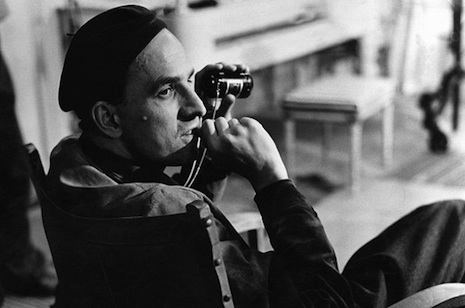

Ingmar Bergman rarely talked about his work, but when he did he could be revealing about his approach to filmmaking and his thoughts about creativity, memory and God—as he is in this interview from 1970.