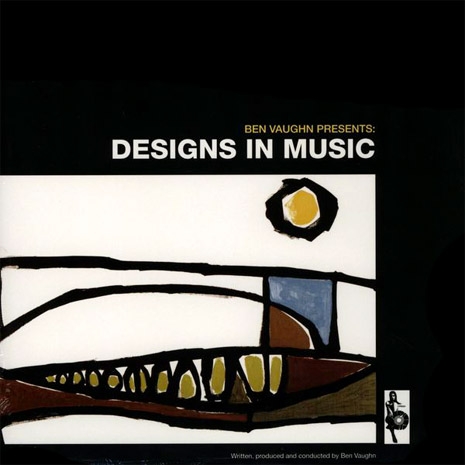

In the ‘oughts, when I was working as an art director at an alt-weekly, I’d often supplement my musical discoveries by raiding the music editor’s stack of unassigned promos. Because we weren’t a particularly undergroundist publication (by then “alt” no longer meant “counterculture”), his rejects often dovetailed rather nicely with my tastes, and one time, some cover art caught my eye well enough that I nabbed the disc though I had no idea who the artist was. It was an abstract painting that put me in mind of that Mid-century moment in art when Surrealism was crossing over into Abstract Expressionism, and the press information that came with it detailed a really charming story about how the music was inspired by AM radio offerings on an overnight drive from L.A. to Las Vegas.

The album was Ben Vaughn Presents Designs in Music, and when I got home and put it on I was transported. The Mid-century visual design affectation was consistent with the music, an utterly mad collision of Duane Eddy/Link Wray reverb guitar twang, orchestral easy listening, Italian film composers, South American pop, Exotica, even commercial bumper music. I have, previously on DM, claimed it as a desert island pick, a call I stand by.

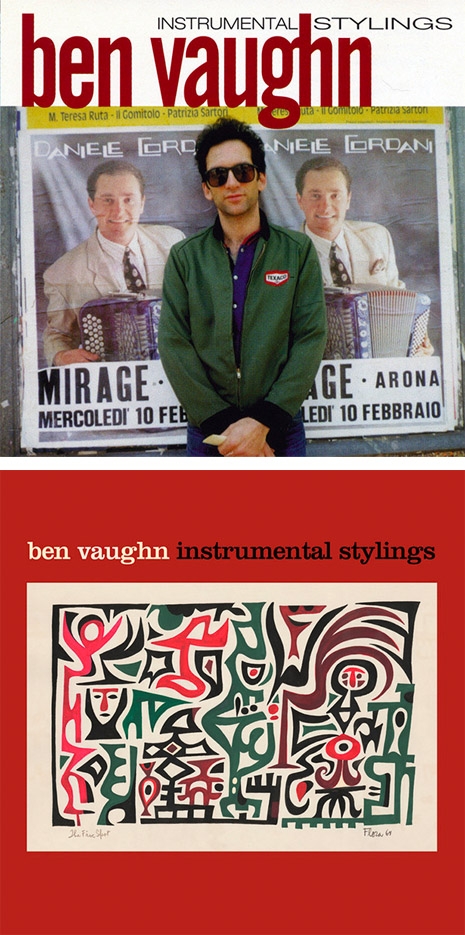

But as it turned out, this wasn’t even close to the first time I’d heard his music. I didn’t catch the connection at the time, but this was the same Ben Vaughn who’d written the theme music for 3rd Rock from the Sun, and who’d transformed the Big Star b-side “In the Street” into “That ‘70s Song,” intro music for guess what show. (He also wrote the theme for the US version of Men Behaving Badly, but I doubt anyone will fault me for never having seen that.) That rather wonderful career was launched when just the right people heard his 1995 Bar/None album Instrumental Stylings. That record’s general vibe isn’t so different from the later Designs—it’s perhaps more guitar-oriented, but it’s no less imaginative. To mark the occasion of its reissue, DM has been given the go-ahead to stream the entire album for our readers, you’re welcome, and Vaughn was kind enough to chat with us about it.

Dangerous Minds: All the different musics you combine into a sort of self-knowing kitsch that’s still really forward thinking and unironic is impressive, and I’m wondering what your inspirations are and what your composing process is like.

Ben Vaughn: I think the difference between homage and parody are lost on me sometimes, maybe more so than for other artists—you mention self-knowing, but I’m not sure how self-knowing it actually is! [laughs] I like to have fun with genres, but I also feel like I’m a part of them. It’s an interesting process for me writing instrumental music, or even writing in general, because I’m such a fan of music from all eras, big-band, folk, blues, jazz, punk rock, The Stooges, everything. So when an idea comes, it kind of comes out of self-education, which is just listening to a lot of music, and the process is hard for me to describe for that reason. Even the way I make records—I come into it on a visceral level, but then there’s a lot of listening and absorbing and data input that goes on.

DM: How did you become such an omnivore? Like what formed those listening habits?

Vaughn: When I was a kid, I was a fan of music before The Beatles came out, that’s how old I am! I was a little kid, but I was tuned in. When I was six years old my uncle gave me a Duane Eddy record, I was at his apartment and he put that on, and this would be around the time when “The Twist” was a craze, so ’62? And Duane Eddy had a record called Twistin’ ’N’ Twangin’, just a guitar instrumental record, and my uncle put it on and I flipped out, so he gave it to me. I’ve probably played it a hundred thousand times.

Then when the Beatles and Stones and the whole British Invasion happened, and Motown happened, I absorbed everything. And AM radio at the time would play Louis Armstrong next to the Beatles, or Roger Miller or Buck Owens next to Wilson Pickett. It wasn’t like that for long, but it was that way when I first started listening to music, so my tastes developed all over the place because radio was all over the place. I never knew that music was supposed to be in compartments until later, and I remember how disappointed I was with such narrow thinking—people who only like hardcore, or people who only like disco but hate punk, or who only like punk but hate disco. I was confused by that. I think about people who only listen to bluegrass—that’s crazy!

DM: Yeah, that to me seems like just listening to one song your whole life.

Vaughn: Bluegrass is kind of the speed-punk of country music! You know what the instruments are going to be, you know the songs are either going to be quick-tempo, fiddle dominated, or you’ll have a waltz. Same thing with punk rock. I’m good with one genre for about three songs, and then I’m looking for something else!

DM: So when did this love of music turn into your profession?

Vaughn: That came late. I got out of high school, I didn’t go to college, not many people in my town did. I worked in a knitting mill, I worked as a landscaper, and all the time I was writing songs and putting bands together, not to play out much, but just to write and rehearse, and frankly to get drunk and high [laughs] and that was really as far as the music went. Right around, I don’t know, 1983, there was a Missouri band called The Morells, people in New York were crazy about them because they were the real deal, they were just regular guys, and they did a lot of obscure covers, and they got ahold of some of my songs and recorded them, and when they came up to New York to tour, all the people who knew who they were wanted to know who I was because they were playing four or five of my songs. That led to me leaving my day job.

Everything changed after that. I wasn’t making money but I was a legitimate songwriter. Marshall Crenshaw recorded one of my songs, and that was a big deal because he was on a major label, and he’s an amazing songwriter, so for him to record someone else’s song was unusual, so the spotlight came on me. From that point on I’ve been professional.

DM: What else have you done that civilians would know?

Vaughn: Well, 3rd Rock, ’70s Show, Men Behaving Badly, and there’s a movie called Psycho Beach Party which has become a cult classic sort of midnight movie now, I did some scoring for that. But the TV work is the only mainstream stuff I’ve done, which I think is ironic, because the record business thought I was too weird. The marketing people at the labels I was signed to couldn’t figure out what to do with me, and I sympathize with them, I wasn’t rebellious or mad at them about it, I agreed, what do you tell people? Am I roots rock, am I a singer-songwriter, am I a guitar player, and what style is it, is it indie rock, alt country? So I was too weird to promote, but you can’t get more mainstream than sit-coms in 1995, and NBC heard my stuff and said “that’s our guy!” It was odd that that’s where my work was appreciated without any suggestions of change.

What got me all that work was Instrumental Stylings. I put that out, and a music supervisor in Hollywood suggested I move to L.A. because Pulp Fiction was just getting ready to come out, and she told me that my style of guitar playing was going to be in demand after that movie came out, because she knew it was going to be a hit. So I moved out there on New Years Day on 1995 with a box of Instrumental Stylings in my ’64 Rambler, and I drove from New Jersey out to L.A., it was like The Grapes of Wrath! And the first thing that happened when I got to L.A. was I was hired to play guitar on a lot of soundtracks, because she was right, that surf/twang style of guitar playing was in demand. There really weren’t that many people in L.A. who could play that way and also show up sober! I was a guy who could take a meeting and listen to what people said and deliver the guitar part, as opposed to being some crazy rock ’n’ roll guy who stayed up until 5 in the morning.

Then, I was being interviewed on KCRW, promoting Instrumental Stylings, and the president of the production company that was working on the pilot of 3rd Rock heard me in her car on her way to work, and she called the station in the middle of the interview and gave me directions to the studio lot to take a meeting about the pilot. By the time the meeting was over they were convinced I was their guy! It was all because of Instrumental Stylings. Glenn Morrow, from Bar/None, he inspired the record. I had put out an E.P of six or seven instrumental songs, and he really liked it, and he told me that if I could come up with a whole album of that he’d put it out. And I was going to L.A. anyway to seek film work, it would be good for me to have an instrumental album, so I quickly recorded, in three weeks, nine more songs, and combined them with the songs from the E.P., it came out really fast. And I was only in L.A. for three months before I had 3rd Rock, and when that went on the air I suddenly had agents wanting to represent me.

DM: Then ’70s Show was next?

Vaughn: Men Behaving Badly was next, then ‘70s Show.

DM: And that was a Big Star song. What was your role in transforming it, how did that happen? It was a partial re-wrirte, wasn’t it?

Vaughn: I was friends with Alex Chilton, and he always told me he thought “In the Street” should have been a hit, and he was disappointed that never happened. The creators of That ‘70s Show were also writers on Wayne’s World, and they’d done that scene with everyone in the car singing “Bohemian Rhapsody.” And they loved the idea of teenagers singing along in a car to their favorite record.

DM: Yeah, my generation’s version of that was “Superman” by R.E.M., everyone in the car was responsible for a specific “I am.”

Vaughn: Yeah! There you go! And they really wanted to do that, and there was this grizzled music supervisor there and he was the guy who could tell you whether they could afford a song or not. And whatever song you came up with—the guy should have been wearing an executioner’s hood! We said “18” by Alice Cooper? “Nope, can’t do it.” “Young Americans” by David Bowie? “You’ll NEVER be able to afford that!” “Won’t Get Fooled Again” by The Who? “No chance!” It was just like strike, strike, strike… so I spoke up and said what about using a ‘70s song that should have been a hit but wasn’t, and they said as long as it’s a great song, sure. And one of the people working on the pilot was a Big Star fanatic, and he had a Big Star CD in his office, so I got him to go grab it, and I played “In the Street” for them and they agreed that that was the song, but they wanted it re-recorded because they felt like it sounded too much like the Byrds in 1966. They thought Big Star sounded out of time with the ‘70s, which is weird.

So I rearranged it, and there’s a longer version that Alex and I did a new verse for, and Cheap Trick used that when they did it. But I went to the studio with a session singer, and we had to cut it really fast, because that meeting took place three days before they filmed the kids singing for the intro. That was already booked, the scene was booked for Friday the kids to record the singalong, and we had that meeting to decide the song on Tuesday so it had to happen fast, like most things in TV. TV is really intense as far as deadline and delivery, which I LOVED, I wanted to write music every day, and the record business doesn’t give you that opportunity. I was getting bored because you only need, really, 12 songs every year and a half, and that doesn’t require much writing. I wanted to see if I could work under pressure, on assignment every day. It was really exciting that something you’re recording today will be heard by millions of people before the end of the week. We cleared the publishing, filmed the kids, did the final mix, and I think a week later it was on TV.

Vaughn will soon be releasing an acoustic LP called Imitation Woodgrain and Other Folk Songs,, and if you live in one of 23 fortunate radio markets, you can hear his weekly syndicated program The Many Moods of Ben Vaughn, a show named after his first album, which features “Rock, blues, jazz, folk, soul, R&B, country, bossa nova, movie soundtracks, easy listening and more, all peppered with Vaughn’s twisted musicological slant.” It is, of course, available as a podcast as well. But you’re here to hear the album that launched his career, so here it is. If you like what you hear, it was recently reissued on vinyl, with fabulous cover art by that late, great, and utterly idiosyncratic illustrator of jazz records, Jim Flora.

Previously on Dangerous Minds:

Post-punk/No Wave vets Double Naught Spy Car’s ‘MOOF’ is spy-fi perfection—hear it here first