On May 29, CAN founder Irmin Schmidt will mark his 83rd birthday with the release of Nocturne, a live recording of his piano performance at last year’s Huddersfield Contemporary Music Festival. A lightly edited transcript of our two recent conversations by phone, quarantine-hushed Los Angeles to nightingale-loud Roussillon, follows.

How is quarantine in Provence?

I’m in the countryside, and everything is calm and beautiful.

What do you remember about the performance in Huddersfield that this record comes from?

Since it was the first concert I did—real concert, I did single performances on prepared piano, small things, but it was the first real concert with the prepared piano, with my new thing—I was quite excited about it, and didn’t know what will happen.

What impressed me was, during the performance, I thought the public had disappeared! It was so silent, I thought maybe they [chuckles]... it sounded as if I’m all alone. They liked it! They listened so concentrated. It went very well.

I actually wondered—on the recording there’s so little audience noise, I wondered if it had been taken out. But no, they were really listening.

They were really extremely silent. There was one very, very little cough, once, in the whole thing. And then the guy afterwards came to me and said, “Excuse me, I had to cough once.” I couldn’t believe it! They were—I mean, as if they weren’t there.

But it was pure concentration there! There were lots of people afterward coming to me and said they were really sort of hypnotized, they really listened. And that was a great compliment, because I didn’t know how would it be. It was a new thing performing this. Although I have, in the Sixties, I made a lot of piano recitals with contemporary music: Messiaen, and Webern, and Stockhausen Klavierstücke, and Cage, a lot of Cage. But this is long ago; in between there were some different things, and that was the first time I was all alone again, facing a public with my piano, and it was wonderful.

It’s sad; I have so many offers now to play all over—in Norway, in Warsaw, in Prague, in Germany and in France—and I can’t do it.

Because of the virus.

Because of the virus, yeah. I don’t worry about it so much because I’m so much better off where I am, in this beautiful countryside. I’m much better off than so many other people in towns. So I don’t… lamentate.

If you have to be stuck somewhere, I would think Provence is not a bad place.

Exactly, [laughs] especially where I am, I mean, I have a big piece of land [signal breaks up] I can be alone and it’s beautiful, it’s calm. No reason to complain.

Photo by Lucia Margarita Bauer

Have you noticed any changes in the environment?

Not really, because I’m living really in the countryside. I mean, it’s springtime, it’s wonderful. There is no change visible because there has never been any traffic in that part of the world.

I mean, the only thing I realize is there are less planes going above our area. But I don’t know, if that affected something, it’s not visible. Actually I can’t say I noticed anything in the environment, because I am not in the town. In towns, everybody tells me it’s totally different; there are more birds and animals. But where I am in the countryside, it’s like always.

But there is one strange thing. You know, our house is called Les Rossignols, our address, and that means “the nightingales,” because there have always been nightingales. There is some water, there is a pond and there is a creek down there, and there have always been some nightingales. This year, it’s double as much, which is the only remarkable thing. There are more nightingales this spring, singing, which is wonderful. I don’t know why. It cannot be because it’s more clean where I am, but maybe it was easier for them to come, I don’t know. But that’s actually the only change, and that can be just a a coincidence. That must not necessarily be due to the lockdown.

Can you tell me about the piano pieces in some more detail? I’m curious first of all what the equipment is. I know on the studio album you have two different pianos, one prepared and one unprepared.

Right. Yeah.

Which I think has been your practice for a while, right?

Yeah, I have two grands in my house. For the studio record, I prepared one and left the other one unprepared, just untouched. On some pieces, I only played the prepared—which, when I say “prepared,” never is the whole piano prepared. It’s never all strings prepared. It’s sort of half of the piano. Because I love this kind of… these vibrations, these sounds of the real piano sound with the prepared, which has harmonics, which create a strange kind of tension between the not-prepared and well-tuned strings, and these prepared ones which have very complex harmonics. I love that.

Yeah, on the studio record, I played two pianos. In performance, in a concert, I can do only one piano, so it’s half-prepared. And you hear it on the Huddersfield recording, there is this mixture between the sounds of the real piano and the prepared piano, and that’s what I love so much about it, because it makes this kind of tension in the harmonics, and these vibrations which are created by the difference of tuned and prepared [strings].

When I made the studio recording, I started with a prepared piano, and the first piece of the studio record is totally improvised. One go. I mean, the time it is on the record, that’s the time I played, and there’s nothing edited and nothing changed and manipulated. That’s how it started.

And then I made some field recordings. I have a little pond, and around the pond there is bamboo and reeds. So I went through them, and sometimes sort of moved them rhythmically, sometimes just went through this, and we recorded that, and I played to that.

Is this the sort of rustling sound on the second piece?

Yes. Yes, exactly. Exactly, that’s “Piano Piece Two,” Klavierstück Zwei on the studio record.

So for the live performance in Huddersfield, I used the field recording as it is for the studio record, I used the identical field recording and played to it. In the live performance, I start all alone, and after a while, these rustling sounds from the reeds come into it. When we recorded it, there was a small plane flying over us, and we kept it, because everything is kept like it happened, and if there was a plane while we were recording the reeds outside, so there’s a plane on the record. I left it on this field recording, and it’s also in the live performance. It creates a very special atmosphere, this rustling sound.

Photo by Brian Slater

And I think there are liquid sounds which may come from the same field recordings, but I have to also ask you about the church bells.

Well, the second piece on Nocturne, which gave its name to the record, the “Nocturne,” is something I recorded actually in my house. I recorded water drops from the tap into the shower and in the kitchen, different water drops dripping from taps. I recorded that with René and then I played to it, and that’s the same thing I do live. It’s the second piece on the Nocturne, I’m playing to the recording of these taps, these drops, and these water drops are recorded for the live performance—they don’t come from the album, they are new [chuckles], newly recorded.

Then, the third piece, these Glocken, these sounds I collected all my life… it started years ago, I don’t know, in the early Eighties I made music for a theater play. I decided because it’s a kind of Spanish author, and it was about religious kind of problems, very strange piece, I decided to make the whole stage music on the basis of these church bell sounds.

And I was so fascinated by the different [bell sounds] that I recorded, ever since, always, from time to time, I have a big archive of bells, and also the mechanism in how the bells are moved, these strange sounds would come from certain mechanisms which moved bells. So I collected lots of sounds like this.

This kind of bell is something which follows me since childhood. I have a very strange kind of relation to church bells. I’m not religious, it has nothing to do with that. It has more to do with my experiences after the War, when I was a child.

The first bell which, really, I never forget was: We were for a while [living] in a ruin, and the windows were open, but it was summer, and the windows—there were no windows. And opposite, the only thing in the vast… well, there was only everything devastated. But the only thing which was still standing there was a church tower, and every hour there was this bell. Ever since, this sort of is something—it followed me all my life, and sometimes I feel very happy with bell sounds, and sometimes they frighten me. Or, “frighten” is not the word, but they bring back something very uncomfortable.

So I have very ambiguous feelings about church bells, and all of a sudden I had this idea, why not make a piece out of that? So I made, actually in the studio, I made this backing track which I composed, like a piece for bells, and then I played to it on the prepared piano. What I’m playing to it is totally free, is always improvised. It’s the same with Klavierstück Zwei and the drops; what I’m playing to the tape is every time different, it’s totally sort of improvised. But “improvised” is not the right word, because it’s already framed by a certain form; not by a tune, but by a kind of atmosphere, which sort of makes a frame for a form.

So the environmental sound is sort of what gives the piece its identity?

In a way, yes. In the bell piece, definitely it does. In the other two pieces on the Huddersfield recording, there are long, long parts where there is no backing track. Like, I start without backing track, then it comes in, and then there is again a long part all alone, and then I play to the drops. But the bells actually, really give the piece its identity, that’s true.

I’ve lived near church bells, and I feel you’ve captured something about them. Bells can be very musical, but they can also sound sort of zombielike and mechanical.

And they can terribly get on your nerves if they are very near to your house, and they wake you up at five o’clock in the morning, and that every day, every hour. Well, that’s the ambiguous thing. Yeah, some bells sound wonderful, really sort of create an incredible space, and others make the space small and even sort of uncomfortable. That’s the fascinating thing about them. And it’s very special. Still, there are bells all over the world. There is, in the Asian cultures, in Japan, and China, and Indonesia [signal breaks up], there are bells, but they sound Asian. That’s the strange thing. All these bells which are used as church bells, all have something in common, comfortable or not, beautiful and great and pleasing—they are all sort of… “Christian” bells. That’s our culture; it’s a narrative about our culture, bell sounds. And that’s what the piece is about.

A narrative about our culture? Can you say more about that?

No, leave it, everything you can imagine about this sentence, because it just came to my mind in this moment, and I don’t want to explain it too much. Bells, there is something mysterious about them, and I don’t try to explain the mystery about it. And one of the mysteries is what I mean with “Christian.” There’s something which unites them all, whether they are in Chicago, or Munich, or Norway, you know. They have something in common which is our culture, and it’s one thing which tells a story about our culture. Well, maybe also something about its beginning and ending.

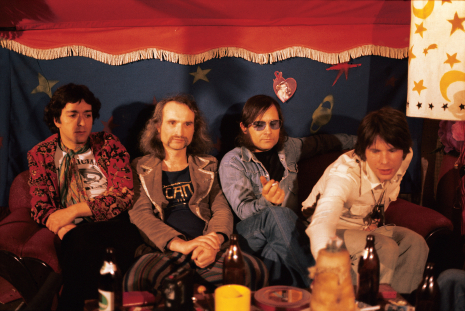

CAN, photo by Gesine Petter

I wanted to ask you about your studies with Ligeti, because while I’m fascinated by Stockhausen and Cage and all the other figures you’ve studied with, I haven’t been able to read much about your studies with Ligeti.

It was in the Folkwang Academy. He was not yet the famous Ligeti at that time. I knew his first orchestra pieces, Atmosphères and things, and I was totally fascinated by his music. And when he came and gave composition courses, I was very enthusiastic and was looking forward to it.

We started I think with about a dozen students in his class. After two of his lessons, we were two students. The others left; they were disappointed, or didn’t want to, because what he wanted, he was making us work hard.

One of his basic [exercises] was analysis, analyzing, say, works of Webern. That was one of the basic things, since I was performing Webern as a pianist. That was one thing. And the other thing was a fascinating course of the art of instrumentation. For example, he asked us: make a piece of two minutes, with two instruments, on one tone. It could have the octave [signal breaks up]. Do that for next week.

And then he said, “Look, we are in a music school, a music university, and you have an orchestra, a symphony orchestra. Find out what sounds, what variety, what richness of tones are possible on the instruments. Make, maybe, a piece for a double bass and a trumpet. But then find out what the double bass can do.” The double bass, for example, is an instrument with incredible, rich possibilities of sound. “So find out about it; get a double bass player and try with him what’s possible.”

So that was one of the bases of his courses. He told us to do research about every instrument in the orchestra, to find out about all the possibilities they can produce, and colors. That was very exciting, because I made quite a lot [laughs] of little pieces on the most strange… I mean, a tuba and piccolo flute, or a violin and trombone, and find out how can you do them sounding together, [so] that you use them with new ears. The analysis courses were very interesting, and you learned a lot about form, but I suppose about forms which existed, because you were analyzing existing pieces. But these pieces we had to do on instrumentation, that was something really exciting, and I learned really a lot. And I understood his compositions much better afterwards, because it’s about color and how instruments, if you use them in a totally unusual way, what they can produce. Yeah, that was Ligeti’s course.

That’s fascinating. It seems like it must have been really useful to you over the years, too.

Oh, yes, of course. Of course! And as a conductor, which was my main study, you have to do research. Especially with me; the other one was an organ player and composer, but I was also conducting, and that was at the time my main thing, learning conducting. And he said, “You, as a conductor, you have to know everything about every instrument, not only how it’s played. Because you will then, even in a Brahms symphony, give hints to a clarinet player being able to hear the clarinet with a different sensorium, with different ears.”

Yeah, that was extremely useful. Even if I didn’t write much for orchestra afterwards, and even if I didn’t become a conductor, or became a CAN member and made very avantgardistic rock music, or whatever you call it—well, sometimes I doubted it was rock music. [Laughter] But, nevertheless, it changed my ears, and it changed my feeling towards music. Even in CAN music… it’s in me, it’s in that.

Well, and you wrote an opera, too.

Yes. And there, of course, is a lot of strange instrumentation which, of course, I would never have been able to do without what I learned with Ligeti.

Do you plan ever to release a full recording of Gormenghast?

I would love to. I would love to have one, to make one, to do one. But, well, quite difficult.

Are there no full recordings of the productions that have already taken place?

Yeah, there are, of both of the different productions, but it’s difficult to make a… in both of them, there are weak things and brilliant things, and I can’t combine them, they don’t fit together, these different productions. And also, it’s a question of rights, and singers, and a lot of problems. You can stream it, but it’s not a real, full recording to my own… I’m not satisfied with it yet. But I would love to make it.

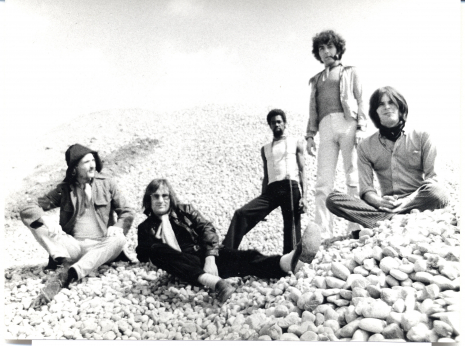

CAN, photo by Mick Rock

Am I right that there are CAN concerts coming out from the archives this year? Is that still on?

Yeah, you are right, there are. The thing is, there is a fan, a friend, who was actually collecting during all our concerts, our tours, collecting tapes. He followed us quite a lot and recorded the concerts, or parts of it, and what he didn’t have, he tried to get from others. He made adverts: “Have you recorded on cassette, or whatever, this concert?” And he collected really a lot. The problem with it is that the recording with most of it is insufficient for [release]. And then sometimes [signal breaks up], so it wasn’t always good, and sometimes it went terribly wrong, and these ones I don’t want to publish either. So to find good concerts with good quality, or say sufficient quality, is very difficult, and you have to listen through hundreds of hours of crap [laughter] until you find something good.

I mean, crap also—sometimes it was recorded so badly, and you hear more of the neighboring voices of the public than off of the stage, and things like this. But you have to get through all of that to find something good. None of us, me neither, wanted to do that, so this big archive of this guy—Andy Hall is his name—all the passion he put in to have all these tapes, was kept a private passion so far. But then Hildegard insisted that I went through it. Andy made a sort of first selection and sent to me about, I don’t know, 60, 70 hours of concerts. I found at least three—well, not full concerts, but sets of an hour or an hour and a half of concerts which were quite good.

We’re remastering them but not reediting. I mean, I left them totally untouched, except we remastered to keep it more transparent, or the sound quality better. And so now we have three, from three concerts: two in Germany and one in England. One in Brighton, one in Stuttgart, and one in Cuxhaven. The first release will be the Stuttgart thing, and then a few months later the Brighton concert, and then Cuxhaven. And then later, maybe some radio recordings; we did some BBC In Concert.

Maybe I find the… well, the guts, the courage, the mood, to go on with this research [laughing] or maybe not, because, I mean, it’s not my favorite occupation to listen through old CAN concerts. But I’m quite happy with these three for a start.

What I didn’t want is, there are here and there single pieces of say 10, 15 minutes, something like this, from single concerts which sound quite okay and are good music, but I didn’t want to have this kind of collage from different concerts, different times, different spaces. I wanted to find something where at least a full hour, or even an hour and a half, of one set of a concert is, because then all these things that are improvised [signal breaks up] take a certain form as a whole set, and this was actually one of the important things of our concerts. Even improvised, they had a kind of architecture, and what I found sort of is typical good CAN concerts, so I’m quite at peace with the release of that.

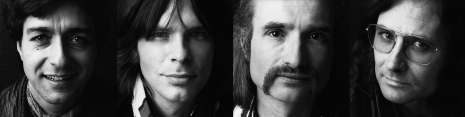

CAN, courtesy Spoon Records / Mute

I’m very curious to hear it. You’ve already released CAN Live as a collection of individual songs from different performances, so hearing a full set—

Yes. There were live recordings already, some of them, on Lost Tapes. That was our archive. But that was single pieces. On Lost Tapes, there was a lot of studio recordings, and some live, and some live in the studio, and improvising, and sort of sketches for film music and all kinds of different work. It was mainly studio.

I was thinking about the box, though, the two live CDs that came with the CAN Box.

Right. Yeah, you are right. Actually, yeah, but I wasn’t too happy about them, except “Dizzy Dizzy” is quite exciting. It’s wild music, but it doesn’t sound so great. And also, it’s single pieces from different concerts, but you don’t get this impression, How was that concert, CAN? How was that? How was it built up? And that’s what I was after, with these live releases, now, to find that. It’s still not up to the standard of live recording, but it’s quite okay, from a technical view, and musically I wouldn’t have allowed [its release if I didn’t] think it’s quite good.

Is there any studio material remaining? I know you’ve just said you don’t want to spend all day listening to CAN tapes.

[Chuckles] No. No, no, no. There is no more studio material. Every studio material left which was worth releasing is on Lost Tapes. That was quite a lot of music, Lost Tapes, and now it’s over. There is still more live recordings like those which we now will release, these three first ones, there is more and there might be some good ones. But for a start, let’s start with these three, and see what happens afterwards.

I mean, I’m 83, and I might not live so long to listen to all these cassettes. [laughter] I’m okay with what we release now; I’m sure there will be more from some radio concerts. This is for sure, this I know, because I listened to it, and that will come after these three first releases, but what comes after this, I can’t predict, because that’s too adventurous to make predictions. [laughter] Although I like adventures, especially in music.

CAN, courtesy Spoon Records / Mute

There’s this sort of mythical moment at the beginning of CAN where you’re supposed to have met Jaki and told him to “play more monotonous.” I wanted to ask you if you remember that encounter.

I mean, I remember the first encounter—encounters, actually—with Jaki. Actually I met him for the first time because he was the drummer of the very famous free jazz group in Cologne, and I listened quite often to their music, to their concerts, and I knew them all, the Manfred Schoof Quintet. One, even two years before CAN, I made a Filmmusik and asked Jaki to [play] a bit of drums for this Filmmusik, so I knew him.

Concerning CAN, when I decided I want to get a group together, I asked him if he knows a drummer—because first, I didn’t expect him to join another group, because he was a member of a very successful—of the German free jazz group, and also, second, I didn’t look for a free jazz drummer, because, I mean, that was so near to what I was doing anyway in contemporary music. I wanted a drummer who played grooves, and my ideal was sort of Max Roach or Elvin Jones, that was the drummers I had in mind. Especially Max Roach. And I ask him if he knows a drummer, a good jazz drummer who is in this direction, and he said, “Oh, I’ll look.”

And then I said, “Well, there are some other guys I’ve asked if they would join, and we’ll meet this and that day in my apartment,” and then Jaki showed up and said “I found one!” I said “Who?” He said “Me. I joined your group.” It was said in a way: I joined your group, no objection. [laughs]

I mean, I was sort of perplexed because I didn’t want a free jazz drummer, but then it turned out when we started playing together that he was fed up with—and that’s what he said, with free jazz, he wanted to make grooves.

But the story that I asked him to play more monotonous… it is a mystery where that comes from. I don’t remember having said that to him. [More the] opposite, that he was always asking the others “Don’t fool around so much, just play one thing.” I don’t know where this story comes from.

Or maybe in the very beginning, there is no mystery about—it was a very straight thing when he came and said “I will be your drummer.” That’s the way Jaki was, he was very straightforward. And, yeah, he played grooves. And it was him who asked the others [to be] more monotonous. Or he decided to play more monotonous; he always said that he decided that he wanted a certain heart of monotony. Which, he succeeded; he became the master of being monotonous, in a very artistic way.

That was always an issue editing the tapes, right? He made sure that the edits didn’t disrupt the groove?

The groove, yeah. And he was bloody right!

Well, you can edit, and make a collage, and willingly put disparate things together, when it makes sense. But when the groove is going on, the groove has to go on, and it’s not to be just, by mistake, sawed off, interrupted. He had nothing against when we cut totally into it and something totally new and totally different… but if the groove was going on and there was a cut, it didn’t really fit. All of a sudden, it changed something. There, he was very, very strict. He was also very, very right!

CAN, courtesy Spoon Records / Mute

Do you remember which Cy Twombly painting you suggested for the cover of Tago Mago?

Well, it’s not exactly like this. I didn’t imagine a certain [painting]. That was in an interview a few years ago. We were talking about our [album] covers. I said that the first cover I didn’t like, the second I didn’t like, the third one, Tago Mago, I didn’t like either.

But at the time, I thought, this is none of my business, because I was new in this kind of world. I had no idea about marketing, about how covers should look, and this. [If] I would have done it myself, maybe I would have chosen a contemporary painting, because all my friends were painters, and I would have chosen maybe a painting of my friend. Or, at that time, I had just seen an exposition of several painters, all totally knew and unknown, that was in Berlin.

And [he was] the one which totally fascinated me, and I got really excited about him—that must have been in ‘60, ‘61, ‘62, around this time. Cy Twombly’s paintings were these typical things he did in the early time. On a sort of white paint-covered [canvas], and grayish, rose, very indistinct coloring, he was drawing with pencil and crayon, like writing you couldn’t read or really find out what it was—these kind of very spooky drawings on it.

And all my painter friends said, “You are crazy. This is not good.” Nobody liked it. I would have loved it on the cover. But I didn’t even propose that to anybody, because I thought they will all say, “Then we just sell five records, maybe,” because everybody thinks it’s crazy. So I didn’t talk much about it. That was more my fascination with Cy Twombly, and it kept going on, until now. He’s one of my favorite painters, of course, because that made such an impact when I saw it 50 years ago. More than 50 years ago. So since this sudden flash, I still love his very early work very much. But it’s not one of them; I like them all.

I don’t think I saw that one I saw in this exposition [again]—because there were only two, maybe two or three of his paintings. It was ‘61, I think, so it’s quite early, of his early work. But especially that one I like very much. These strange little fragments, very sparse, very open, drawing with pencil and pen and crayon, but little, very little, few colors.

And it was something totally new, absolutely new. Later, after I got more into the subject, I found out of course there is references to history, especially to Cézanne’s drawings. But at that time, it seemed something absolutely new and unknown.

But I was right! I mean, I saw that, everybody said, “Ah, bullshit, it’s nothing,” [laughter] and he was one of the great painters, famous ones. So my judgment was right.

Irmin, I’m a huge fan of yours, and it’s been a pleasure talking to you. Thank you for your time. Is there anything else you wanted to say? Is there anything coming up in the near future?

No. Well, the future was actually me doing my piano recitals on prepared piano, like Huddersfield, in different places. This, at the moment, is not happening. I’m stuck to my home—which is a wonderful home, so like I said in the beginning, I don’t complain about that—and to my piano and to my desk. And on my desk is a lot of music paper for writing scores, 32 systems, and I will start to write an orchestra piece.

That’s wonderful news!

Which is another adventure. Since I cannot get anywhere else, and have to be… well, “house arrest” [laughs], sort of, a comfortable musical quarantine which I might use for writing a piece for orchestra. If I succeed. [signal breaks up] Yeah, probably the whole summer I will stay here and work on this piece. There might, one day, be an orchestra piece. That’s all I know about the future. [laughs]

Anyway, I’m not so much thinking about [the] future. More important is, how is it said, “presence of mind.” Being in the present, living in the now. Just working with the possibilities every now has.

That’s the quality of attention we started out talking about, how attentive the audience was at Huddersfield.

Yeah.

I suppose that’s part of—being in CAN was like that too, right? Very focused attention?

Yeah, it’s absolutely what I mean with presence of mind. It’s really, totally giving itself up into what you are doing at the moment, and that’s what was in CAN, that was the main thing. Yeah. Presence of mind.

Nocturne will be released on CD and vinyl on May 29. Order from Mute and Amazon.