_465_769_int.jpg)

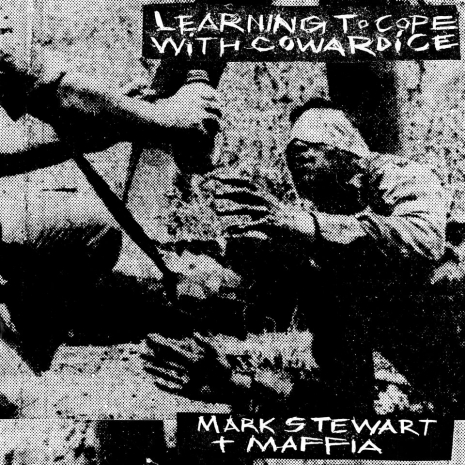

Illustration from the cover of the ‘Jerusalem’ 12-inch and the ‘Mark Stewart + Maffia’ compilation

Head above the heavens, feet below the hells, the singer Mark Stewart has embodied the international rebel spirit since he fronted the Pop Group as a teenager, giving voice to activist and imaginal concerns shared by punks, Rastas and b-boys. Mark Stewart and the Maffia’s moving, mind-mangling, amazing debut album, 1983’s Learning to Cope with Cowardice, whose sounds still beckon from an unrealized future, will be reissued on CD, vinyl and digital formats tomorrow, supplemented by an extra disc of recently discovered outtakes that differ radically from anything on the finished album. Sales of the double LP edition benefit Mercy Ships, an organization that provides lifesaving surgeries to people in poor and war-torn countries around the world.

I spoke with Mark Stewart last week by transatlantic telephone line. After he expressed his respect for Dangerous Minds, affably breaking my balls about the post in which I outed him as the owner of the face in Discharge’s logo, we talked underground media and mutual aid briefly before settling in for a discussion of his solo debut and the current historical moment. A lightly edited transcript follows.

Mark Stewart: I’m so pleased to be working with Mute again, and Daniel Miller has kind of rejuvenated Mute, and the independents—it’s a pleasure, you know, to work with cool people where something flows, you know? It’s really important for us that there’s those kind of columns in the underground.

Dangerous Minds: Holding it up.

Holding it up.

I wouldn’t have asked you about this, but I interviewed Adrian Sherwood the day after the Brexit vote, so it strikes me as funny that I’m talking to you now, right after the deal failed. Do you have anything to say about the situation?

I think it’s a total distraction. [laughs] I think it’s a complete smokescreen, and I’m very scared what’s going on behind the scenes. It’s like, I was watching something about Goebbels’ control of the media on some history channel, right, and how he learned from Madison Avenue. I’m not taking a position right or left on it, but I think it’s the most bizarre distraction in the last few years, and God knows what’s going on. But, you know, behind the scenes, our health [services]—there’s all sorts of things, all these laws are being passed behind the scenes, but that is the only thing journalists are looking at. Not the only thing, but do you understand what I’m saying? That isn’t a comment against whoever and whatever.

The problem is, in England, and I’m not being rude, is it is so class-ridden, it’s a problem for both sides of the spectrum. I was living in Berlin for a while, and I was talking to a very cool Japanese guy yesterday, who’s translating this friend of mine, Mark Fisher’s, this theorist’s book on capitalist realism. And in Germany, and I think until fairly recently in Japan, skilled laborers were treated with ultimate respect. The unions worked with the entrepreneurs, or the bosses, or whatever, and there was a kind of “synergy,” to use a wanky name, and so the economy was quite strong, and there was a social service system. . . you know, Germany’s quite an interesting model. But here—the craziest thing is, people are speculating, people are making big money out of these sudden changes, they’re spread-betting against these sudden changes of polarity, you know? I was reading, ‘cause I always read all sides of the spectrum, I was reading in a financial thing, suddenly sterling has got very, very strong. You know? And these politicians are being played. Do you know what I mean? They’re being played.

I can sit and talk to a Tory boy, I can sit and talk to whoever. And I’ll listen to people and try and talk to them in their language, and try and understand their point of view, right? ‘Cause being opposed to people, you don’t really get anywhere. But they think they’re doing something for whatever bizarre, medieval idea of nationalism or identity politics or whatever you call it, and there are some—there used to be this thing in England which was called “caring conservatism,” which was quite feudal, it was like how the king of the manor would give the employees some bread. [laughs] Scraps from the table or whatever. But here, the problem is, the working class are envious of the rich, and the rich want to squeeze the working class until it explodes to get every drop of blood out of them. It’s quite a strange system. And the middle ground that you’ve got in Germany, with the, whatever they’re called, Christian Democrats or something; back in the day, when people like Chomsky and everybody used to attack these middle-left kind of parties—you know, I read a lot of theory, but now, that is heaven compared to what’s happening these days! “The center cannot hold.” Everything is just. . . it’s bizarre, you know?

Adrian Sherwood and Mark Stewart, London, 1985 (photo by Beezer, courtesy of Mute)

But the problem is, again, my personal Facebook is full of loads of cool people who I really respect, so I get utterly impressed when, like, these Italian theorists start talking to me about how this album or our early work inspired people to get into different ideas about the planet. But I’m sick to death of people moaning about these non-events, which could be like—it’s like an orchestrated ballet of distraction. You know, it’s bollocks! “Never mind the bollocks” is never mind the fuckin’—it’s bollocks! And people are constantly talking about it.

And what I would be doing—so many of my American friends are just constantly posting this stuff about Trump, right? And I’m like—sorry, I’ll probably lose a lot of respect for saying this, I’m sorry, but as soon as the polls were looking like that, the guy’s been democratically elected, we’d roll up our sleeves and try and organize for 10 years down the line, if not five years down the line, and try and grow some sense of hope! Spread seeds of hope, culturally, in these small towns. That’s what things like punk are about. You know, with punk, a youth center opened, or a squat opened, and little places changed a bit, you know? Now people are just tutting. Saying “Oh, he’s bad”—so what? You’re bad for not fuckin’ doing anything! Sorry to rant, but there’s this culture, this narcissistic culture of wallowing in defeat. Which is basically another way of saying “I’m not going to do anything, but I’m gonna pretend to have a conscience by tutting.”

Yeah, people are glued to their TV sets and the news constantly, and it makes them feel powerless, and they don’t do anything. I don’t know if it’s a similar thing with Brexit.

I don’t know. I think people make a choice not to care from an early age. I’m not being rude. You can blame this, you can blame something outside of yourself, but as I grow a little bit older and I get more pulled into weird, sort of Taoist sort of things, it’s to do with putting a foot forward and breaking outside of the mold, and if you get hit, you get hit. Or if somebody says you’re a nutter, like they said about us back in the day, you know, or they say you’re wrong, or whatever, at least you stepped forward, outside of the embryonic—do you understand what I’m saying? You have to do provocations. In my sense, it’s kind of art provocations. What I do is, even if I’m not sure about something, I think It’s enough of a curveball to go in that direction, or to spin against my own stupid sense of conditioning: sparks will fly. Let’s go! Let’s do it. Do you know what I mean?

It’s this sitting back—and now you’re getting people kind of reminiscing about the Cold War! Which again was a distraction. It’s just nonsense, you know? People want to live in this nostalgic bubble. And now they’re saying that the fuckin’—a journalist in an English paper was saying that the Cowardice times were more paranoid than now? What the fuck? [laughter] With Cambridge Analytica, we got fuckin’ algorithms—if there was a Night of the Long Knives overnight and somebody got control of the algorithms, thousands of people could just be rounded up for reading Dangerous Minds. Do you understand what I’m saying? And it’s all sold to the highest bidder; there isn’t even any politics involved. It’s naked capitalistic control. But, you know, now I’m moaning like I shouldn’t have done. Daniel Miller had this idea of enabling technologies, and in America, there was always like Mondo 2000 and Electronic Frontier Foundation. So I’m positive as well as being. . . it’s very interesting times. And when there’s change, there’s possibility.

One of the main reasons I wanted to interview you about this record is that “Jerusalem” is one of my favorite recordings.

This one, or another one? My one, or somebody else’s?

No, your “Jerusalem” is one of my favorite records. Part of it is, there’s the Blake poem, which has all this revolutionary, visionary significance, but then there’s so much layered on top of it—all this patriotic meaning, and it’s in the hymnal, and I don’t know if you know that story about Throbbing Gristle playing at the boys’ school and the boys singing them offstage with “And did those feet in ancient time”—

No.

—so I wonder if you could tell me about what that song means to you, and whether you were trying to recover some of the William Blake in that song.

Well, it’s a long, long, long story, and a lot of it’s got to do with an ancient tradition of kind of English, kind of Celtic mysticism, which is—I’m gonna sound like David Tibet now or something—but I’m a Stewart, right? And our family history is linked to this other family called the Sinclairs. My father died a couple of weeks ago, and he was a real, to use the word nicely, occultist. He was a Templar, and he taught remote viewing. But for me, I feel, growing up near Glastonbury—this might sound very, very hippie, this, but it’s the kind of mysticism of Blake that I really liked, right? There was a review in the Wire, when the record first came out, back in the day, and they said me and Adrian, it was a perfect alchemical marriage, or something. If you can be kinda hopefully mystical at the same time as being hopefully an activist, there’s an uplifting sense of that tune in specific.

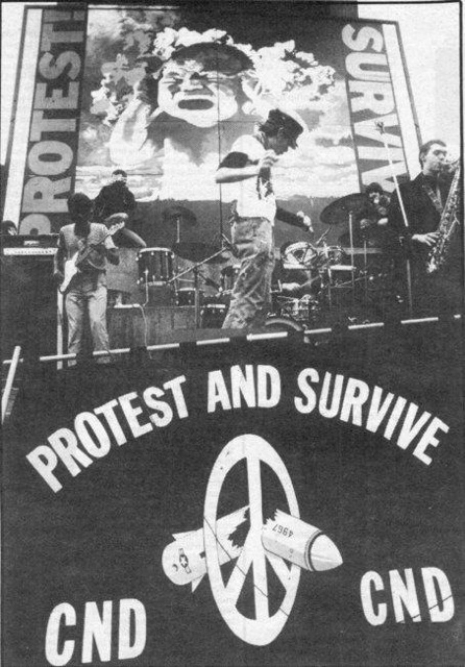

Mark Stewart and the Maffia’s first performance, CND rally in Trafalgar Square, 1980 (courtesy of Freaks R Us)

What happened was that the last ever Pop Group concert and the first ever Maffia concert were on the same day. Basically, I’d got sick to death of music, I’d kinda packed it all in, I thought we weren’t ever gonna get anywhere with it, and I was just bored of it, right? And I became a volunteer in the office of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament in London, in Poland Street, right? And one day in the office, Monsignor Bruce Kent, who was in charge of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament at the time, we were organizing what turned out to be the biggest postwar demonstration against nuclear weapons, and the center of London was brought to a standstill by 500,000 people. People came from far and wide, from Scotland, from everywhere. And he turned round and said, “It might be good to have some music,” ‘cause, you know, Tony Benn and all these amazing people were speaking, and I said, “Oh, I’ve got a band!” And I said, “I can ask some of my mates.” So I asked the Specials and Killing Joke; Specials couldn’t do it, but Killing Joke did it, and we ended up playing between the lions in Trafalgar Square. My brother and loads of my weird artist mates did this huge kind of amazing mural of this baby coming out of this atom bomb.

Basically, I was thinking to myself, What would be a classic rallying song, that people young and old—you know, ‘cause very few people would have known about the Pop Group in this demonstration—young and old, like Woody Guthrie, or Pete Seeger, or something like “We Shall Overcome,” what would be good for England? And immediately I thought of “Jerusalem.” And the Pop Group was going all sort of free-jazzy and out there and stuff, where I couldn’t get it together with the Pop Group. I was already hanging out with Adrian and starting to make some sort of reggaeish stuff, so the first version of the Maffia got up and played “Jerusalem” and a few other songs a few hours later in the day, ‘cause people sing it on marches and stuff in England.

So that was the reason for the “Jerusalem” thing. And that moment, that moment in the middle of London, you know, it was the proudest day of my life, to actually be involved in—I’m just trying to organize something just now, just before you phoned, to try and kick off a big sort of demo this year, because that’s what gets me going! It’s like when we used to do Rock Against Racism; we did stuff for Scrap SUS, when they used to just stop black kids on sight and search them, the police; Anti-Fascist League, you know, and now we’re doing this stuff for these Mercy Ships people, who build these boats—they do up these old kind of trawlers and park them out in international waters, outside war zones, and make them into little floating hospitals and operate on kids and stuff. That’s what the money from the limited vinyl’s going towards. But it’s just like—when it’s a benefit, you can get other cool bands. There’s a band here called Fat White Family and all these offshoots of them, Black MIDI or something, there’s these conscious young bands who are mates of mates, and I know in a couple of phone calls I can get an amazing bill together, and the people around me aren’t gonna ask for so much money, they’re more likely to answer the call, you know? And people remember those events for years to come.

Well, I remember you said something in an interview years ago, “The political and the mystical go hand in hand.”

[laughs] I always say the same bollocks! You’ve caught me out!

No, no, no! I think it’s important: the political people always think they have to be hardheaded and materialist, and the mystical people always think that they have to rise above the accidents of history—

Rise above what?

You know, the political and the everyday, and that kind of thing. Do you know what I mean?

Yeah, yeah, yeah. You’re hitting on something I’ve been thinking a lot about the last few days—yeah, good to bring that together.

This version of the Maffia—was this the On-U Sound crew of musicians, before you met Keith and Doug and Skip?

Yeah, there’s a bit of a funny story. Let me just say this little bit. The interesting thing was—Zoe sent me something saying you wanted to talk about the influences on this record, and just going back to something I remembered earlier on, ‘cause I try and prepare a bit before the thing, so I don’t repeat myself about the mystical and political every eight years [laughter]—and that’s the problem with the internet, people just see the same, “Oh, he’s talking the same bollocks again, trying to get 50p off us” [laughter].

Basically, what happened is, with the Pop Group, we were the bee’s knees in New York. I was just reading this thing about when New Order were over in New York. Basically, us and the Gang of Four, before that, in ‘79, ‘80, or whatever, were like the hippest bands in New York for, like, Ruth Polsky, we were playing at Hurrah’s, and I was, like, half living there, right? But all the people I was hanging out with were just, like, amazing, ‘cause I used to read Andy Warhol’s Interview in this little newsagent’s in Bristol and dream about going to these—I used to imagine to these weird clubs in New York, with Jobriath in them or whatever. I end up hanging out in New York, it was the beginning of the No Wave time; Thurston Moore said he came and saw us, and Gareth was rolling around playing his saxophone covered in glass splinters, or whatever. Anyway, in that Pop Group New York period, I was really consuming what was happening in New York at the time, and I was messing about with the radio stations. Every Friday night—I think it was Friday, don’t quote me—I found this show early on either WBLS or KISS, this Red Alert show, and Red Alert was a DJ and he had scratches and stuff for Bambaataa’s Zulu Nation, and they had some sort of scratch DJ battle, and it BLEW MY FUCKIN’ HEAD!

We took these tapes back to Bristol, and that’s what kicked off the Bristol hip-hop scene. All my mates, we had double cassette machines, we were all copying the tapes, and it was going ‘round. Delge, before he was in Massive Attack, he was a graffiti kid, he was like drawing a graffiti thing on these little stickers we’d put on them, like fake covers or whatever, and I hear that Banksy said that this album and that period in Bristol is his favorite time. These early kind of Maffia gigs with the reggae lineup were crucial to Bristol kicking off, and the St. Paul’s Riots were happening at the same time. And I’m proud of Bristol to this day because there’s this tradition of bass that’s going through to these young kids like Ossia and Giant Swan or whatever.

So what happened was, I was constantly going to loads of reggae concerts in Bristol, and blues dances, and I went to see this guy called Ranking Dread, and I saw the drummer play. And I’m one for just kinda going up and talking to musicians; you know, I went up and talked to Allen Ginsberg when he did some reading, and he started arguing with me, saying I was exaggerating the apocalypse. Like we used to go and talk to Roxy Music, and talk to the Clash, or whatever, when we were kids, we’d just go up and talk to people after the thing. And this drummer was, like, wicked, and he was almost kind of—like a steppers reggae thing, but almost kind of mechanical, a bit like. . . I don’t know, and I was into Metal Machine Music by Lou Reed. Anyway, so I realized he played with Adrian, or Adrian was using him in Creation Rebel, and then I got another guy from a reggae band that played with us and Public Image called Merger. There was a lot of interplay—and I was living in Ladbroke Grove, half the time, as well as Bristol—there was a lot of interplay between, like, us, and reggae bands, and black activists. We were friends with Linton Kwesi Johnson, I was working with these people called the Radical Alliance of Black Poets and Players, you know, Darcus Howe, there was a newspaper in London called Race Today—there was a lot of interplay, probably the same as in the sixties with the Watts Prophets, or whatever. I had my feet in that kind of culture as well, because I’m a bass head.

And then I got to know Adrian because Adrian was working a bit with the Slits, and he came to Bristol with another amazing Jamaican toaster called Prince Hammer, and me and Adrian just kicked it off straightaway, you know, we’re still like best mates to this day, we’re putting out something new that’s just been announced, blah blah blah blah blah blah. And it flows, it flows. The interesting thing is, when Adrian was working, all these kinda crazy kind of old classic Jamaican guys would pass through: Lee Perry, I remember having breakfast with Prince Far I—he’s going “Where’s my porridge?” in his classic voice—and Deadly Headley, the sax player on this album, he’s like the John Coltrane of Jamaica. He comes from—there was a thing called the Alpha Boys School where they looked after orphan kids in Jamaica and taught them instruments, and all the best horn players came from this [school]. You know, I’m not in awe, but I’d sit with these guys, you know, and I’m amazed how these incredible people. . . I don’t know if they took me seriously, ‘cause I was quite drunk half the time; when you’re 20 or something, just having a laugh. But I’m quite big, and I can look after myself. It was amazing; it still is. It’s magical, to be with people like that, and then a few years later, for Doug and Keith and Skip to let me run with these crazy ideas. A couple of times, people would say “Why are you destroying a good song with all these tape edits?” I’m like, “Shut up!” [laughs] “Fuck off back to America if you don’t. . .”

Well, that’s one of the reasons I think the record holds up so well. I never get tired of listening to it because the mixes are so extreme, and your ears never get—

It’s out there, it’s out there. The production process of trying to get these sounds through, like, the mastering and manufacturing process, and people trying to normalize—“Oh, there’s something wrong.” An early review said “I think my needle’s broken.” I went “YES!!!” Fuck ‘em.

Photo by Beezer, courtesy of Mute Records

Adrian Sherwood says you edited this at Crass’s studio. Does he mean Southern by that?

Yeah, Southern. And that goes ‘round a complete circle, because a cool guy at WFMU or something in the States, I make friends with people, and he just approached me and said, “I’m getting all these weird people to do a version of a Grant Hart Hüsker Dü song.” I didn’t know anything about Hüsker Dü; I said “Well, who’s doing it?” He said, “The guy from Chrome,” and I just said yes straightaway. So anyway, I was trying to pull in some of my American mates, so I got Mike Watt to play on it. And I suddenly thought, I’d really like to do something with Ian MacKaye from Fugazi—although it’s not totally my area of music, I’ve had ultimate respect for him and people over the years that have had dealings with him. And I just got his email off Mike Watt the other day and emailed him about trying to do something together, and he said “Oh, I met you at Crass’s studio,” because Crass were distributing early Dischord and early American hardcore and stuff. It was a very fervent time, Jesus and Mary Chain were recording their first stuff in the other studio, and it was like a really, really interesting mixture of crazy people.

I did something with Penny Rimbaud the other day. Crass: they blew so many people’s minds! I’ve got a lot of time for these kind of. . . the work they did. I just saw the Sleaford Mods’ touring schedule, right? And they are going to every buttfuck town in fuckin’ England. They’re gonna change attitudes, do you know what I mean? It’s a bit like, there was a Bristol band called the Vice Squad, the second generation of these shit English kind of pub rock bands which American people thought was punk rock [laughs] ‘cause they’re the only ones that toured outside Pittsburgh or something, right? But: respect, you know? And Crass really changed people. There was a techno crew later called Spiral Tribe that, every time I meet somebody cool in Portugal or Vienna or something, they were all, their heads were blown at some Spiral Tribe rave. They were mates of Mutoid Waste. They did amazing, and all power to them, all power to them. And the independents—the politics of independent distribution, again, Crass’s label; On-U Sound, Adrian was using the same distributors; Freaks R Us, our label; Y Records, a label I was involved in; ZE; Wah [?—maybe WAU! Mr. Modo?]; Mute; Rough Trade—the politics of, like, taking these crazy noises in to a label and doing mental kind of montages on the guy’s floor, and them running with it and not saying “Oh, can you dye your hair pink?” Do you know what I mean? It gives you the freedom to kind of get near to what you want to say!

What’s the new thing with Adrian Sherwood you mentioned?

Basically, I’m always doing kinda new stuff, right? And we did a couple new Pop Group albums. And Mute were talking about reissuing Veneer of Democracy and some of those Mute albums, and luckily a lot of crazy material has turned up in, like, vaults in Portugal—crazy story about these lost tapes. But all the way through, I’m constantly doing loads of new stuff for whoever, right? And doing a couple of collaborations and this and that and whatever, and I’ve got like two or three albums worth of new stuff, so I’m trying to work out a way of placing something. Hopefully, kind of like we did with the Pop Group: use a couple of classic reissues to kind of push forward. And then, what I would like to do is, use a couple of reissues, and then a new thing—you know, there’s a media cycle. You can’t put too much stuff out in the year, but I’ve got some brand new stuff going on. And Adrian suddenly phoned up and said, “I’m gonna do another Pay It All Back,” which was this classic series that I used to help with back in the day. The first one was like 99p. And he’s got the first new track from me for like eight years, brilliant new stuff from Lee Perry, Horace Andy who works with my friends Massive Attack has done some great stuff—it’s a brilliant compilation, and that’s just been announced today. It’s coming out like a month after this thing [i.e., the Cowardice reissue], and I’ve just made a kind of cut-up video of it, so that’s the first kind of new thing. It’s good to do that under Adrian’s umbrella, and then kind of move forward and look ‘round and see what the terrain’s like. It’s a funny game to play. Punk is very digital at the moment.

What’s the story about the lost tapes you alluded to?

So I don’t spend a lot of time, like—I remember having a conversation with my friend Richard Kirk from Cabaret Voltaire a couple years ago, I was going, “How are you?” And he’s a bit of a funny Northerner, he’s going, “Oh, Mark, for the last year I’ve been archiving 1975.” [much laughter] I just thought fuck you! I mean, I keep shit—I’ve got a lockup in Berlin, there’s this really cheap supermarket here and in Germany called Lidl, I scribble one-liners I’ve ripped out of a magazine or something, onto, like, these stupid food catalogs. I hoard stuff like that, but just, like, archiving all this stuff. . .

But the craziest thing is, over the years, you meet real characters, traveling round the world, and there’s a lad that I always go for a drink when I’m in Ghent—crazy guy, crazy guy, I just go out with him to a few bars. He’s more hyper than me! Patrick Dokter, right? And he loves On-U Sound and my stuff, and he self-appointed himself to be an archivist, and he’s hilarious, right? And somehow, I was up at Adrian’s like a year after we made the Cowardice album, and he was moving, or decluttering, or something, and there were all these boxes of quarter-inch master tapes outside the house, and it was pouring with rain. I wasn’t thinking about the future then; I just thought maybe we could reuse them. You know, Lee Perry only had one bit of tape he made all his albums on, and just recorded over the top of it, in Jamaica in that Black Ark studio. And he said, “Oh, there’s no space for all this stuff,” I think maybe he was having another kid, “I’m gonna chuck it out.” I went, “Oh, right.”

Mark Stewart and Prince Philip, 1983 (photo by Kishi Yamamoto, courtesy of Mute)

And so all these tapes that were on this kind of porch somehow ended up in Portugal; it’s like Raiders of the Lost Ark, right? From Portugal, my crazed kind of Dokter archivist—it’s like the Knights Templar looking for Solomon’s treasure, right? This guy has spent—worse than Richard Kirk, he’s spent the last three or four years baking, he’s made his own kind of weird, like, homemade kind of baking and studio thing, transferring and repairing these old reel-to-reel machines or something. Yesterday I found out he’s found loads of more stuff, and Adrian, with these On-U reissues, Patrick is, like, supplying amazing stuff! And Patrick said, “Oh, I’ve got these outtakes from that period.” I was going, “What do you mean?”

Basically, the story was, I’d have tapes, reel-to-reel tapes, running all the way through the sessions, because a lot of the songs on the real album were kind of Kurt Schwitters, Dada collages of like 10 or 12 mad dub mixes. On one mix, the drums would be dubbed to fuck like a road drill, on the next mix the vocal might be alright, but halfway through. . . and on the real album, “None Dare Call It Conspiracy,” 87 pieces of tape were on the wall! And we decided to put some backwards and some forwards, ‘cause Adrian had met some guy in New York, this amazing 12-inch guy that would cut the tape down the middle and have one stereo thing running in an opposite direction to the other stereo thing. George Morel, his name was. Absolutely amazing. These days, they’d call it messthetics or tape manipulation, plunderphonics or something.

What happened is, on these tapes, there’d be like half an hour of me and Adrian, like four o’clock in the morning, a bit out of it, listening to, like, a hi-hat go “fsh-ksh” [laughter]. And me trying to copy these hip-hop beats really badly, before samplers, with, like, a jack plug, trying to trigger a cassette machine or something, pissed on cider. Or hollering, really out of tune; my mum says it sounds like dogs. Hours and hours of complete and utter nonsense.

Me and Adrian spent more time going through these fuckin’ mental tapes, finding nuggets and compiling it into something which I think flows quite well, and they’re the actual, real versions of the songs before we fucked them up! Some quite sound like ballads, or something. And the original version of “Jerusalem.” I’m pleased. Two completely unknown songs, which I didn’t even know had existed. And the lovely thing about Mute is we have total control over putting all this artwork together, and I’m working with this Italian theorist who did an essay, and some of the money can go to this Mercy Ships charity.

This crazy analysis of the post-punk era doesn’t seem to stop. Over the years, you see waves of things come back in or go back out again, but this kind of psychic archeology on the post-punk era—there’s so many bands here, and when I was in Germany, and even in art and theory and stuff, I’m really into semiotics, Baudrillard and stuff—people are repeating, in a different way, with different source material, alchemical experiments that we did back in the day. And so, I’d love it if people feed off my carcasses, do you understand what I’m saying? And make another mutation out of it.

Yeah, it’s not just nostalgia. It’s something else.

No! It’s not. Nostalgia, for me, it’s that weird alchemical thing where the snake eats its own tail.

The Ouroboros.

It’s fine, as long as I have control over what goes out, and the mastering, and it’s politically kosher, then yes.

So does that mean there’s gonna be expanded reissues of your rest of your—

“Expanded reissues,” that sounds like Warner Brothers. With “video content,” and a secret video link to my—yeah, I’m gonna be like the guy from KISS, I’m gonna come and perform in your house.

[helpless laughter]

For 800 pounds, I’ll come and do a black magic ceremony with Boyd Rice! No, I’d better not say that. We’ll do genital piercing, we’ll do body modification with outsider artists—me and Jandek.

[helpless laughter]

While I’ve got you laughing, I’m really getting into experimental dance, I mean, that’s the new me. I’m not as slim as I used to be, but there’s something about fuckin’ experimental dance that I do not understand. At all. I mean, I’m trying to find out about the Zohar, or something, at least I can get my head around medieval mystical texts, but experimental dance? I can watch it for two hours and not know what the fuck is going on, and it puts me into a trance state, which I quite like. So I’m working with this—I don’t know if you saw the video for “Liberty City,” I’ve made friends again with this old Turkish mate of mine who does anti-gravity dancing, and he’s off his fucking block! [laughs] It’s like a night out at the pub every second with him. He just runs into walls and gets funding! [laughter]

It sounds a bit pompous and wank, but I’ve got some idea about making a gig a bit more sort of performance art, you know, and out there. I was talking to Daniel Miller about it, I’ve got this book about experimental Russian plays in the 1920s, and there’s just like a cart upside down—Ubu Roi sort of stuff. Anything that gets away from the normal fuckin’ bollock-y fuckin’ trad-jazz. . . do you know what I mean? Throw a fucking curveball.

Is it true that Hugh Cornwell financed the first Pop Group demo?

Totally. Basically, in Bristol, we were playing youth clubs, and we tried to get support shows with whoever we could, and we wound up going all the way down to Plymouth and supporting the Stranglers. And the guy who was on the mixing desk at the time was Dick O’Dell, who went on to manage us and did Y [Records and Y the Pop Group album], and as soon as he started telling us in the soundcheck he’d worked with Alex Harvey Band and Bowie and stuff, we just thought, we wanna be mates with this bloke, starting trying to buy him some beers, and Hugh thought we were really cool. But the interesting connection was, I think we took Charles Bullen from This Heat to the session, ‘cause we were really into This Heat. And, I’m up in London quite a bit these days, the kid I work with down the road is best mates with Charles Bullen, and I’ve been hanging out with Charles a bit after all these years, and he’s just done a mix of this thing I’m doing later in the year for the American cancer charity.

There’s amazing people. . . I love it. I’ve never ceased to have a sense of wanderlust.

Mute’s reissue of Learning to Cope with Cowardice comes out tomorrow, January 25. Below is the new video for “Liberty City.”