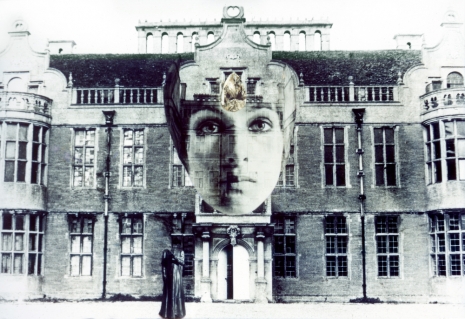

Penny in frame from 16mm film Lilford Hall, 1969, by Penny Slinger and Peter Whitehead

My reaction upon recently being exposed to the work of Penny Slinger, a bold and penetrating surrealist multimedia artist from the U.K. who produced her most striking work in the late 1960s and 1970s, was to suppose that there must have been a mistake of some sort. Slinger’s work, which spans photography, collage, and sculpture, uses techniques of surrealism to address highly pertinent topics of sexuality, gender, and identity in ways that make quite a few people uncomfortable—which is all to her credit, of course. What I could not comprehend, given the stunning clarity, precision, and power of her work, was her relative lack of recognition, a matter that a new documentary by director Richard Kovitch seeks to remedy.

The movie, called Penny Slinger: Out of the Shadows, places the pressing question of the artist’s rediscovery—as well as a major theme of her work—squarely in its title. Born Penelope Slinger in 1947 London to a middle-class family, Slinger attended art school in the mid- to late 1960s, where she was exposed to the work of surrealist Max Ernst, whose art seemed to address many of the questions that Slinger felt most needed addressing. (Later she got to know Ernst.) In 1969, while still a student, she produced a book of ambitious and bracing photocollages, falling into the rubric “feminist surrealism,” under the title 50%—The Visible Woman. In 1971 Slinger became involved with a feminist art collective called Holocaust, which produced a theatrical work in London and at the Edinburgh Festival titled A New Communion for Freaks, Prophets, and Witches—one of Slinger’s primary characters in that production was called simply “The Shadow Man.” This evolved into Jane Arden’s groundbreaking movie, in which Slinger played a major part, entitled The Other Side of the Underneath, which to today’s eyes might come off as something like a feminist Zardoz without being either self-evidently funny or a failure. That movie was marred by a dreadful incident in which the husband of the cellist and composer involved with the movie immolated himself in an obscure attempt at protesting of the movie. Out of the residue of that experience Slinger produced the splendidly focused book of photographic collages based in an abandoned mansion in Northamptonshire, titled An Exorcism. If Slinger had produced nothing but An Exorcism, her career would be well worth celebrating. But there is much, much more.

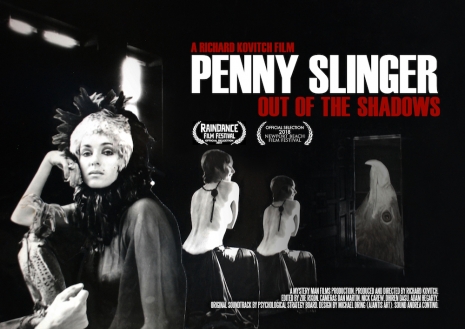

Poster for Penny Slinger, Penny Slinger: Out of the Shadows (2016), featuring Bird in the Hand, 19.25” x 13.25”, collage from An Exorcism (1977), courtesy Riflemaker Gallery, London. Copyright Penny Slinger.

In 1977, Slinger, following her muse, largely abandoned the world of bracing high art in favor of authorial explorations into Jungian sexual archetypes and the introduction of Tantra into the modern world; works include Sexual Secrets: The Alchemy of Ecstasy, Erotic Sentiment in the Paintings of India and Nepal, and The Pillow Book.

One would have thought that a female artist with work as profoundly arresting as Slinger’s would have become a household name, but in many ways the chameleonic and elusive nature of her work resulted, perversely, in lack of recognition. It could be argued that her work fits in much better with our notions of art today than they did back then, in other words that we’ve caught up to her, rather than the other way around.

As I stated earlier, a new movie about Slinger is on the horizon that has the potential to transform the artist’s currency among the art aficionados (and regular art fans) of our own day. Penny Slinger: Out of the Shadows is still currently playing on the festival circuit in the US and Europe and screened earlier this year at the Tate St. Ives. The movie takes as its subject Slinger’s life and career from her birth up to the late 1970s, after which her visibility as a cutting-edge, provocative artist regrettably diminished. Penny Slinger: Out of the Shadows investigates in detail the themes of Slinger’s work as well as the salient biographical details of her life, which (I assure you) readers of Dangerous Minds are well-nigh guaranteed to find of great interest. We get to see a great deal of Slinger’s work, which (as already stated) has a knack for holding viewers’ attention. Slinger herself is on hand for interviews in which she clarifies how things looked from her perspective, as are several of her key collaborators as well as a handful of commentators from the art world or academia to supply valuable context.

Kovitch has told me that he is hopeful that a DVD/VOD distribution deal will solidify in the near future. Speaking personally, I cannot wait for this movie to find a broader viewership because it does such an outstanding job of placing Slinger’s career in context and teasing out the manifold ways in which her work speaks to us in the second decade of the 21st century. For anyone tracking the intersection of surrealism and gender, it’s an essential work.

Invitation, photo collage from An Exorcism, 19.75” x 12.75”, 1970-77. Copyright Penny Slinger.

A few weeks ago I spoke on the phone to Slinger, who currently resides in the Los Angeles area. At 70, she is as alert and insightful as ever.

Dangerous Minds: There’s a tension in your career of addressing political topics but also listening to your own inner voice, which is by definition not entirely amenable to politics.

Penny Slinger: Yes. Well, I’ve always marched to the beat of my own drum. If I found something that I could be in alignment with, I totally would, but I’ve never been particularly keen on “external politics,” I’ve always been much more intrigued by internal politics and the politics of experience, believing that only with that knowing of the self and those interconnections made on an interpersonal level, only then, with that frame of reference, can you actually be the enzyme that can make change in a bigger way on the outside. I’ve always had rather grand—and “dangerous”—ideas in terms of the status quo, but I haven’t really wanted to go out there waving banners and propagandizing, I’d much rather bring things forth through the alchemy of my art, and believing in that kind of refinement process. When you do that and then present it, it has much more deep and long-lasting effect than maybe just the turning of a political coin, which will always turn back again, so to speak.

DM: There’s something similar happening in terms of your own career, which is that you attended to your inner muse so assiduously, while maybe not making certain tactical choices that would have helped you.

PS: I did make a choice to follow my spiritual path and my muse that called me on a deeper sense rather than take the opportunist way, if you like. When I was young, I thought, “I’m gonna be, you know, Lady Picasso.” I always believed that I had a destiny to become this huge, powerful artist and, as a woman, turn the tide on what we’ve seen in the art world and I always saw myself as that. Some kind of superstar complex, I guess! But then I didn’t make choices often in my life that were going for that, so to speak. I made choices that felt true to my own path and my own integrity. So I don’t regret anything that I’ve done because it felt true. That’s my path and I followed it to the best of my ability. In terms of the wisdom of building a career, hmmm… I know that I’ve made choices that took me in other directions. But if one looks at the big picture, all these have been part of my mandala, part of my path. You know, the sum of the parts is greater than those particular incidents along the way. And now, at this point in my life and my age, where you percolate and distill things, I look at it all as one holistic journey, and I’d say that right now I feel it’s the time to tie those threads together, and try to be as on the case as I can, and to make a place for myself, so that what I still have to say can be heard. The last part of my desire to manifest things in this world to effect change, has been around something I’ve pondered about for a long time, which is ageism, especially for women. The fact that when you’re no longer a sexually magnetic person out there, that you’re really not of use in this youth-centric society. I always felt that this was totally wrong and that one should gladly claim and own one’s wisdom and experience and be able to have a way to put that back into society. I feel that’s why we [as a society] have stayed immature is because that voice hadn’t really been heard. So this is the piece that I’m now trying to be true to, to be relevant at this time, deeply relevant from the span of things I’ve encompassed. I’m still growing and evolving and still making things that are on the cutting edge. What I was doing was on the cutting edge when I was younger. Many people have followed in those kinds of directions, but it doesn’t mean that there aren’t other frontiers to be crossed at every time, and I feel that’s what I am consciously and constantly doing.

DM: Do you think that in some sense, the sexual world has caught up to you in some ways, rather than the other way around?

PS: Well, yes, let’s look at feminism, for instance. I never called myself a feminist because I didn’t feel in alignment with that political movement in the way it was manifesting at the time. But right now the way that feminism has encompassed more, and especially the feminine body and all the qualities of woman being important to be recognized—not just women being seen as equal to men in the workplace or something - now I feel more that that was always what I was saying, so I can feel more attuned. And then of course the things that have changed so radically in terms of gender definition… I’d always felt that the roles that we’d been shoved into that were gender-specific were very limiting. We all have male and female energies inside, and a creative act is the union of those male and female energies, and so we didn’t want to be limited into these boxes, and what people now call gender-fluidity is something that definitely played a role over the time that I’ve been alive and has evolved.

DM: The word balance comes up a lot in the movie. You’re not looking to shortchange any energies, male or female.

PS: Exactly. We don’t want to put anyone down, it’s just that women have been put down a lot for a long time, so it’s their time to rise up, not to then dominate, but to have a healthy kind of equality and for the female qualities in men that have been so suppressed, to everyone’s detriment and even the planet’s detriment, to have a way to emerge.

DM:You experienced some frustrations working on The Other Side of the Underneath, which led to your making some adjustments in your approach, which led to your book An Exorcism.

PS: Yes. Well my engagement with the Women’s Theater Group was something I wanted to do because I was looking for a way to not be an egotistical artist but actually be part of a group. I’d been keen on surrealism but then surrealism wasn’t really an active movement, so I was trying to find somewhere to connect in. So doing something with other women and collaborating and co-creating felt right on the nail for me. But then when the theater production was translated into the film, it became much more Jane’s project, and so one wasn’t able to have that same kind of interactive co-creative dynamic that was to me the heart of it, and the heart of the women coming together. So instead we were all telling her story and looking at her psychosis.

It was a very powerful experience. Peter said he didn’t want me to do it. He especially didn’t want me to do the erotic scene with Jack (Jane’s partner). I’d told him about it because I didn’t want to do anything behind his back, but then, when he did say no, I couldn’t in all truth to myself jump ship then. Jane had said that Peter could come up and [participate in the erotic scene] with me, but he didn’t want to do it because he wasn’t keen on the whole project. After the dreadful suicide, I didn’t want that to happen to him. That event made me try to stick together with Peter, whereas before, when I came back from filming, I thought “It’s going to depend on how he reacts. If he’s all kind of closed down and doesn’t like the new me (I felt I had grown a lot), then we’ll split up, no problem. If he is OK, we’ll go to further heights together, and this will be great.” But then it got complicated, and there wasn’t any simple solution any more after this person died, and I tried to do everything I could to keep the relationship alive, but I couldn’t.

DM: And this led to An Exorcism.

PS: We’d taken the photographs together when we were there (at Lilford Hall) and we were trying to make a movie and it didn’t really happen. I had this set of photographs, and in fact, Peter reminded me when I saw him a couple of years back to do an interview, that we actually had both decided we’d do two sets of photos and he was going to do his photo collage to express himself and I was going to do mine. That seemed like a very interesting experiment. Then he never did his set. He said he’d realized it was really more my thing than his.

I was using the series and the process as a tool for self-psychoanalysis. I was trying to recover from this traumatic situation, the breakup, and to explore… I thought, I’ve got to know myself and I’ve got to find out why I’m feeling all this pain, and what are the roots of it and how does it go back to my childhood and my relationship with my father, etcetera, and the sense of abandonment. I wanted to look at all sides, the factors I was facing and see how much was mine, how much is the inner, inner me, how much was projection, and how much was what we inherited from our social matrix. I was just going on this journey to find out, who am I? And I thought this great empty derelict mansion house, my father’s house, so to speak, an empty mansion, was the perfect setting. I was looking at all of it, looking at a situation of why I didn’t feel totally empowered within myself and why this loss of the male energy was so devastating. Why did he have the key and I didn’t have the key to my own inner space ? I worked on the project for seven years all together. It was a rite of passage for myself, out of the relationship and out of the old and into the new.

I have always believed that the ultimate path of the artist is one of full integration, where there is a transparent interface between the life of the artist and the work they produce. The art is the reflection, but, unlike the case of Narcissus, the artist is constantly reforging that image of self in their alchemical fires. So there is no time to hang around being intoxicated with how they appear. It is a constant work of self transformation and, unlike Dorian Grey’s portrait which aged as he stayed young, this portrait reflects back the truth of their path with as much candour and integrity as possible.

I am very thankful to Richard Kovitch for putting so much time and effort into making this film because I think it really makes the interweaving of my life experience and my art very palpable, tangible, visceral, undeniable.

Here’s a brief sequence from Penny Slinger: Out of the Shadows followed by a trailer for the movie:

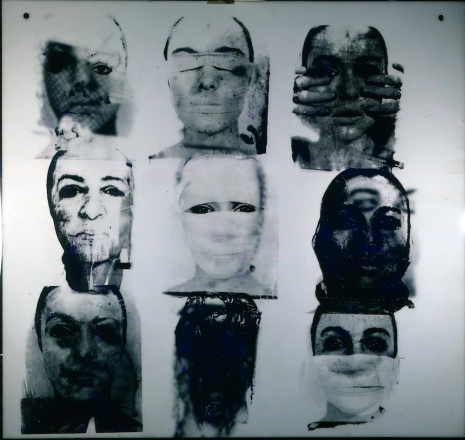

Faces, silkscreen printed on plexiglass 30” x 32”, 1969. Copyright Penny Slinger.

Self Image, photo collage from An Exorcism, 20” x 13.5” 1970-77. Courtesy Riflemaker Gallery, copyright Penny Slinger.

Penny with Erotic Wedding Cake (from Knave Magazine article). Dummy wedding cake, life casts, mixed media, 22 x 22 x 42 inches, 1973. Copyright Penny Slinger.

Penny in “Shadow Man” hat. Black & white photograph, 1971. Copyright Penny Slinger.