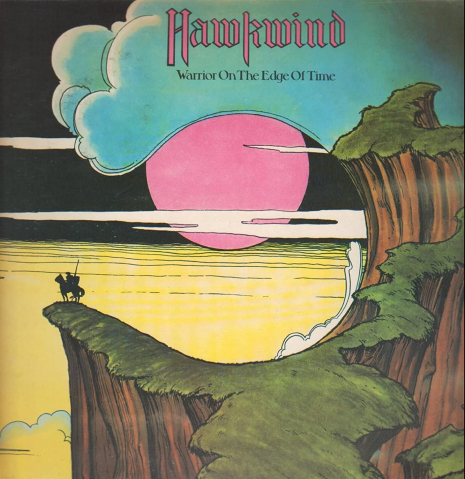

Cover by John Coulthart

1975 was a watershed year for Hawkwind – it marked the release of what for many fans is the band’s finest album, but also saw them lose their most famous member… In an edited extract from Hawkwind: Days Of The Underground – Radical Escapism In The Age Of Paranoia, Joe Banks revisits its tumultuous first few months.

In the first week of January, Hawkwind enter Olympic Studios to record two songs for their next single: ‘Kings Of Speed’, a co-write with Michael Moorcock, and ‘Motorhead’, a Lemmy-penned paean to amphetamine abuse. The Drum Empire are pleased, particularly with the first of these. Alan Powell tells Sounds: “It’s very powerful – it’s got two drums on it and it sounds fucking great. It’s like a Phil Spector thing.” Simon King more accurately says, “It’s the same as ‘Silver Machine’. Well, near enough, anyway”.

Amid a flurry of music press front covers, Hawkwind get back on the road again. In February, they play four shows in London in quick succession: the East Ham Granada Cinema, twice at the Hammersmith Odeon, and of course the Roundhouse. Melody Maker editor Ray Coleman’s Hammersmith review contains an eye-catching assertion: “Their music sounds like good, solid punk rock to me.” And the headline is ‘Hawkwind: Punk Masculinity’.

‘Punk’ is a term initially popularised by US writers such as Lester Bangs to describe a stripped-down, no frills approach to rock – and it’s telling that Hawkwind are now being tagged this way. Coleman describes audience and band as “creating an intensely private event”, and being “members of a secret society.” In other words, the UK’s biggest cult band, a gathering point for those still committed to the values of the underground, but also the crucible of a new type of anti-establishment feeling, as some in the audience prepare to cut their hair and embrace anarchy.

For Dave Brock, it’s like a war. After a show at the Birmingham Odeon, Melody Maker’s Allan Jones describes him as shell-shocked, “an exhausted counterfeit of his dramatic space warrior stage persona.” Touring has become a ceaseless military campaign – he’s conflicted by their level of success, but also worries that they might have peaked. Like Nik Turner before him, he’s concerned about losing contact with the community that spawned them. Unlike Pink Floyd’s middle class audience, who “sit there comfortably”, Brock says, “ours is a predominantly working class audience, and we want to keep tickets as cheap as we possibly can. We want to get close to the audience.”

It’s not a complete surprise then when the final British dates are cancelled. A spokesman explains that after two UK and three US tours in 12 months, everyone is physically and mentally shattered: “Matters came to a head at London Roundhouse last Sunday when about a thousand people who had been unable to get in tried to burn down the side entrances, and the police had to be called.” Even Turner accepts there is no alternative. He apologises for the cancellation, but “there was no way the band could continue without time for a rest.”

After time out to recuperate, they return to Rockfield Studios to record their next album. While they’re away, the ‘Kings Of Speed’ single is released, but it fails to set the charts alight. Speaking in April, King seems sanguine enough – “I didn’t like the number anyway” – but gives an insight into how Hawkwind are becoming increasingly alienated by the mechanics of the music business: “We had to do a single to fulfil our record contract… People kept on saying to us that it had to have this, had to have that. In the end, the band didn’t want to know.” He’s more satisfied with the album though, despite only having three and a half days to record at Rockfield, and three days to overdub and mix at Olympic. Why the rush? “We’re soon to tour America. Atlantic, our recording company over there, needed an album to coincide with our visit”.

Peaking at number 13 in the UK charts, Warrior On The Edge Of Time is the highest placed of Hawkwind’s studio albums, and the last to feature on the US Billboard chart, at 150. Not only does it confirm Hawkwind’s ongoing popularity, it also consolidates and reinforces their position as musical flag bearers of a thriving science fantasy subculture. Ever since J.R.R. Tolkien’s Lord Of The Rings became required reading for heads everywhere, the counterculture has been drawn to both the imagery and philosophy of fantasy literature – its portrayal of alternative societies locked in battle with the forces of darkness chimes with a new generation banging its head against the strictures of the straight world. The likes of Led Zeppelin may have amped up Tolkien’s romantic, ‘mystic macho’ vibe, but Hawkwind are drawn to Michael Moorcock’s more nuanced treatment of order and chaos.

Predictably, certain critics can’t wait to put the boot in. Melody Maker’s Allan Jones, a man seemingly condemned to write about a group he has little time for, makes concessions about the album being their most professional yet. But the main thrust of his antipathy is that he simply doesn’t like the idea of Hawkwind – they’re not what he thinks a rock band should be. The partisan Geoff Barton at Sounds is more positive – but concludes, “Even the band’s publicist admits that you can’t really expect too many people to enjoy the band’s albums.” Presumably said publicist was given their marching orders soon after.

While UK fans dig into Warrior, a drama is unfolding overseas. On 11 May, crossing from the US into Canada, the band are stopped and searched. As a long-haired rock band with a reputation for narcotic indulgence, this is an entirely common occurrence and they’re used to ensuring that all vehicles and personnel are drug-free. But this time, their luck runs out: Lemmy is found in possession of two grams of white powder. Believing it’s cocaine, the border police arrest him and cart him off to jail. The rest of the band make it into Canada and apply for Lemmy’s bail. But they have a gig in Toronto scheduled the next day, and Brock instructs band manager Doug Smith back in London to put ex-Pink Fairies guitarist Paul Rudolph on the first plane over.

The charges against Lemmy are dropped when the powder proves to be speed rather than coke, and he arrives in time to play the show. But at a band meeting afterwards, Lemmy is sacked. His arrest is the final straw, grievances having built against him due to his constant lateness and continued enthusiasm for amphetamines. “They must have wanted me out,” Lemmy surmises glumly. He claims that Turner declared he’d leave if Lemmy returned, though Brock does ask him back – but by then, Rudolph has taken his place, and Lemmy has decided to form his own band instead.

Lemmy’s departure is arguably the most significant personnel change to occur within the band so far. A firm favourite with both fans and media, and a defining presence during Hawkwind’s rapid ascent from the underground, his playing has had a profound effect on the group’s sound, injecting both rhythmic drive and unexpected melody. If not the heart and soul of Hawkwind, he’s certainly been their guts, the low-end throb that Brock has relied upon to provide a flexible backbone during passages of improvisation. And of course, he’s forever the guy who sang ‘Silver Machine’ and encapsulates the band’s anarchic outlaw spirit.

For many fans, this marks the point where Hawkwind’s ‘classic era’ ends…

Hawkwind: Days Of The Underground – Radical Escapism In The Age Of Paranoia by Joe Banks is published by Strange Attractor Press

The incredible promo film made for the “Silver Machine” single.