The most famous short film ever made was inspired by dreams. Luis Buñuel and Salvador Dali had talked about making a film together for some time but could never agree on what the film should be about.

One day, Dali told Buñuel he had dreamt of ants swarming in his hands. Buñuel replied that he had dreamt of slicing open someone’s eye with a cutthroat razor. “There’s the film,” he said, “let’s go and make it.”

As Buñuel later explained, they compiled the script from a series of images which they took it in turns to suggest to each other. There was only one rule:

...No idea or image that might lend itself to a rational explanation of any kind would be accepted. We had to open all doors to the irrational and keep only those images that surprised us, without trying to explain why.

When one of them made a suggestion, the other had three seconds in which to say “yes” or “no” to the proposal. This was how Buñuel and Dali wrote Un Chien Andalou (1929). Their intention had been to shock and offend, but rather than offending the public, Un Chien Andalou became an notorious success, which left Buñuel feeling ambivalent over his new found fame:

What can I do about the people who adore all that is new, even when it goes against their deepest convictions, or about the insincere, corrupt press, and the inane herd that saw beauty or poetry in something which was basically no more than a desperate impassioned call for murder

The most infamous image in cinema history?

The film had been paid for by Buñuel’s mother, but their next movie L’Âge d’Or (1930) was commissioned by the arts patrons Marie-Laurie and Charles de Noailles. This time their film achieved notoriety after Dali declared it was an attack on the Catholic church. When screened in Paris, the film caused a riot and was banned for 50 years.

After this, Buñuel distanced himself from Surrealism and became a Communist—a decision that ended his friendship Dali and led the painter to damage Buñuel’s reputation in America by denouncing him as an atheist.

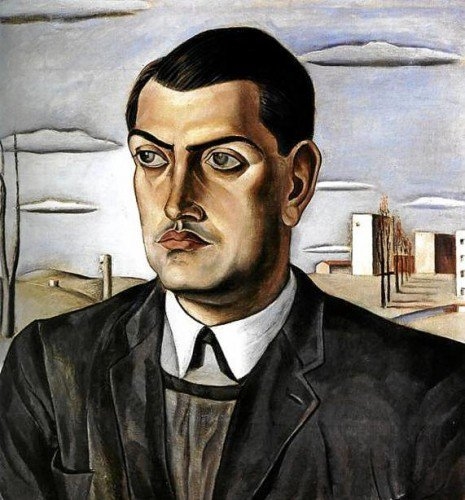

Dali’s portrait of Buñuel from 1924.

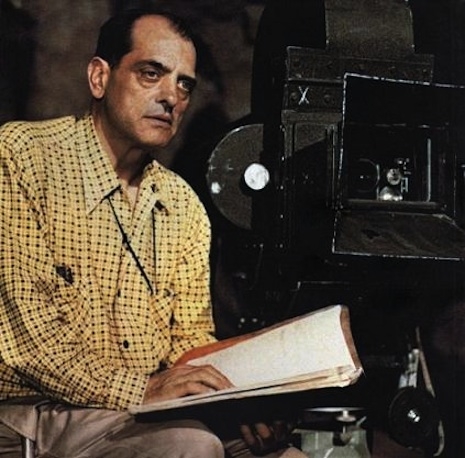

It would take until the late 1940s for Buñuel to re-establish his career as a film director when he started making B-movies in Mexico. In 1950, he co-wrote and directed Los olvidados (The Young & The Damned) for which he Best Director at the Cannes Film Festival in 1951.

In 1960, Buñuel wrote “A Statement” on filmmaking for the magazine Film Culture in which explained his views on cinema:

The screen is a dangerous and wonderful instrument, if a free spirit uses it. It is the superior way of expressing the world of dreams, emotions and instinct. The cinema seems to have been invented for the expression of the subconscious, so profoundly is it rooted in poetry. Nevertheless, it almost never pursues these ends.

We rarely see good cinema in the mammoth productions, or in the works that have received the praise of critics and audience. The particular story, the private drama of an individual, cannot interest—I believe—anyone worthy of living in our time.

If a man in the audience shares the joys and sorrows of a character on the screen, it should be because that character reflects the joys and sorrows of all society and so the personal feelings of that man in the audience. Unemployment, insecurity, the fear of war, social injustice, etc., affect all men of our time, and thus, they also affect the individual spectator.

But when the screen tells me that Mr. X is not happy at home and finds amusement with a girl-friend whom he finally abandons to reunite himself with his faithful wife, I find it all very moral and edifying, but it leaves me completely indifferent.

Octavio Paz has said: “But that a man in chains should shut his eyes, the world would explode.” And I could say: But that the white eye-lid of the screen reflect its proper light, the Universe would go up in flames. But for the moment we can sleep in peace: the light of the cinema is conveniently dosified and shackled.

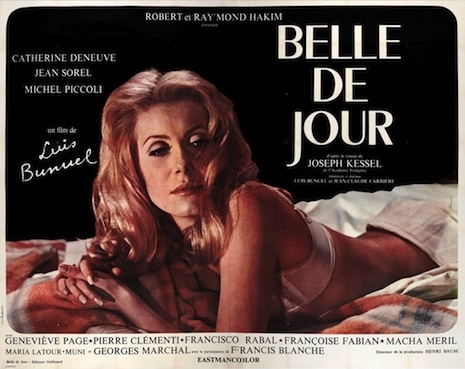

A late starter, age did not diminish Buñuel’s talent as a filmmaker and his most successful movies were made when he was in his sixties and seventies—The Exterminating Angel, Belle de Jour, The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie and That Obscure Object of Desire.

Buñuel said he was “An atheist—thank God,”—a line (allegedly) pinched by Kurt Vonnegut, and the only thing he equated with religious passion was his favorite drink a martini. In his autobiography, My Last Breath, Buñuel offered his recipe for the definitive martini:

To provoke, or sustain, a reverie in a bar, you have to drink English gin, especially in the form of the dry martini. To be frank, given the primordial role in my life played by the dry martini, I think I really ought to give it at least a page. Like all cocktails, the martini, composed essentially of gin and a few drops of Noilly Prat, seems to have been an American invention. Connoisseurs who like their martinis very dry suggest simply allowing a ray of sunlight to shine through a bottle of Noilly Prat before it hits the bottle of gin. At a certain period in America it was said that the making of a dry martini should resemble the Immaculate Conception, for, as Saint Thomas Aquinas once noted, the generative power of the Holy Ghost pierced the Virgin’s hymen “like a ray of sunlight through a window-leaving it unbroken.”

Another crucial recommendation is that the ice be so cold and hard that it won’t melt, since nothing’s worse than a watery martini. For those who are still with me, let me give you my personal recipe, the fruit of long experimentation and guaranteed to produce perfect results. The day before your guests arrive, put all the ingredients-glasses, gin, and shaker-in the refrigerator. Use a thermometer to make sure the ice is about twenty degrees below zero (centigrade). Don’t take anything out until your friends arrive; then pour a few drops of Noilly Prat and half a demitasse spoon of Angostura bitters over the ice. Stir it, then pour it out, keeping only the ice, which retains a faint taste of both. Then pour straight gin over the ice, stir it again, and serve.

(During the 1940s, the director of the Museum of Modern Art in New York taught me a curious variation. Instead of Angostura, he used a dash of Pernod. Frankly, it seemed heretical to me, but apparently it was only a fad.)

In 1984, a year after his death, the BBC produced a documentary on The Life and Times of Don Luis Buñuel, which covered his life from eye-ball slicing to his plans for deathbed pranks to be played on his family and friends.