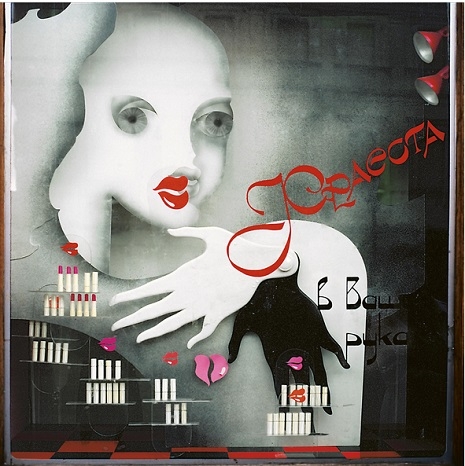

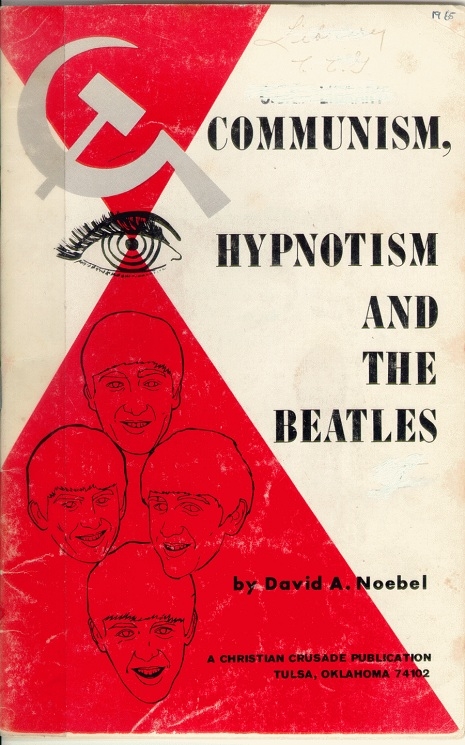

‘The Butcher’ (1990).

Not every Russian citizen was pleased to see the end of Communism in the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics during the 1980s and 1990s. Some, like the artist Geliy Korzhev (1925-2012) thought the changes wrought by perestoika were a betrayal of all the lives sacrificed in order to bring true equality to the Russian people. Korzhev thought the great socialist revolution had hardly started before it was being betrayed and abandoned by the politicians who had lived so well from it, while others had paid the price.

Korzhev was a hardline Communist who never gave up his political beliefs. In the 1980s, he began painting grotesque and surreal paintings of this new world of Russian capitalism he and his fellow Soviets were being forced to embrace.

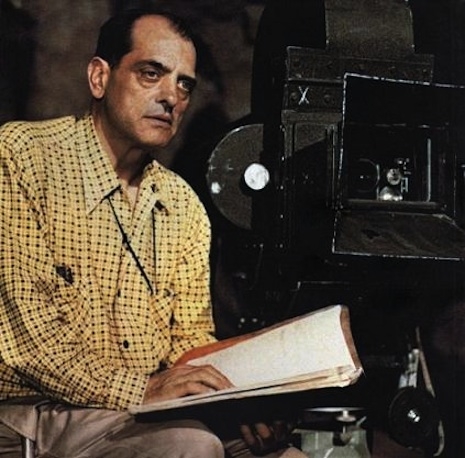

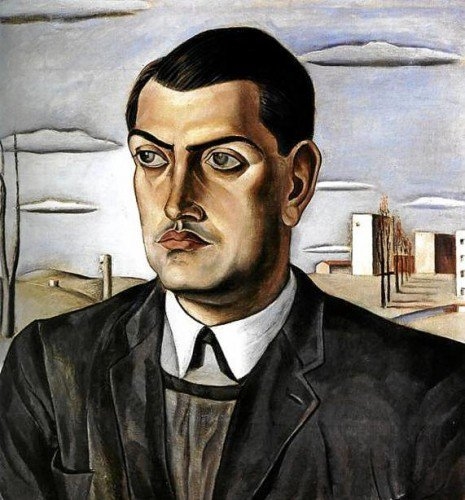

Geliy Mikhailovich Korzhev-Chuvelev studied at Moscow State Art School from 1939-44, where he excelled at drawing and painting and went on to become one of the greatest artists of the approved style of Socialist Realism. According to the Museum of Russian Art:

[Korzhev] is recognized by contemporary Russian art historians as one of the most influential painters of the second half of the 20th century; his work has influenced the style and subjects of two generations of post-WWII Russian artists.

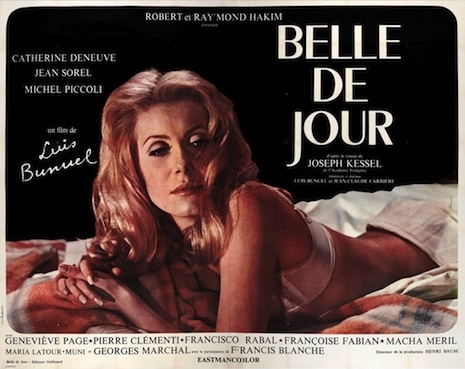

Korzhev’s painting developed from the basic propagandist needs of Socialist Realism into a more personal and highly artistic style. His work ranged from the traditional Soviet style to a more Impressionistic studies. Then in later life he progressed towards a highly surreal and almost Bosch-like approach with a series of allegorical works. These attacked the political corruption and folly of the new Russia. They depicted weird parasitic creatures devouring the flesh of citizens and bizarre monsters celebrating their worst excesses. His paintings were disturbing, thought-provoking and radical in their revolt against the new capitalist politics of the time.

Korzhev made his first mutant paintings in the 1970s when he felt the Soviet leaders were ceding their belief in Communism. This was confirmed with the arrival of Mikhail Gorbachev the great reformer who started the dissolution of the Soviet Union. Throughout the eighties, Korzhev worked in “silent opposition to the new Russian leadership.”

Unwavering in his views, in the late 1990s the artist refused a state award bestowed upon him by the government of the new Russian Federation.

In a note explaining his decision, Korzhev wrote of his motives:

“I was born in the Soviet Union and sincerely believed in the ideas and ideals of the time. Today, they are considered a historical mistake. Now Russia has a social system directly opposite to the one under which I, as an artist, was brought up. The acceptance of a state award would be equal to a confession of my hypocrisy throughout my artistic career. I request that you consider my refusal with due understanding.”

It is said that Korzhev “did not seek to openly criticize the political or social system of contemporary Russia” but from his paintings during this time it is difficult not to see how the political loss of faith in the Soviet state did not affect his work.

In 2001, he said:

“For those who are running the country I have, as Saint-Exupery put it, a deep dislike. Those circles that are currently flourishing and are now at the forefront hold no interest for me. As an artist, I see absolutely no point in studying that part of society. The people who do not fit into this pattern, however - now they are of interest. The ‘superfluous’ men, the outsiders - today, they are many. Rejected, ejected from normal life, unwanted in the current climate… I am interested in their fate, in their inner struggle. As far as I am concerned, they are the real, worthy heroes for the artist.”

Among his last works were a hammer and sickle and portraits of the new Russian Adam and Eva.

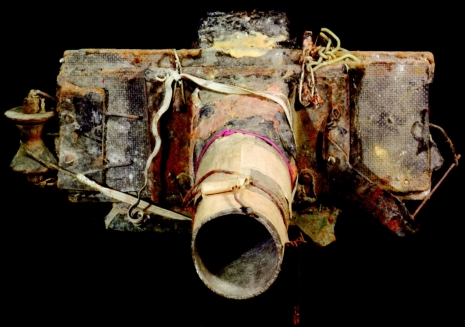

‘Real’ (1998).

‘The Butcher #1’ (1990).

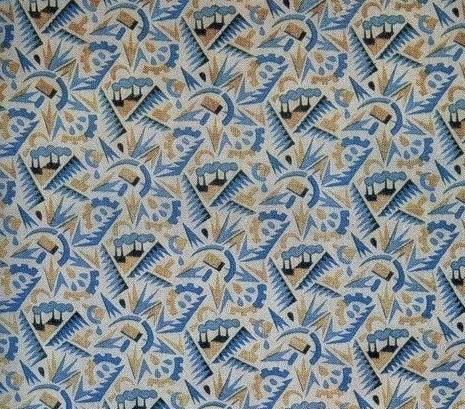

‘Mutants’ (1990-93).

More of Korzhev’s weird paintings, after the jump…