Stanley Kubrick’s 1979 movie adaptation of Stephen King’s The Shining continues to exert unusual power over audiences, as seen in many ways, most notably the appearance of a film several years ago named Room 237 dedicated to elaborate fan notions of the movie that strayed well into conspiracy theory terrain.

Many have called attention to Kubrick’s mastery over “the uncanny” to explain the movie’s grip on us. Narrative elements (as well as geography and architecture) don’t add up, there is an excess of production skill over narrow plot points as Kubrick allowed horror tropes free rein. It’s perhaps not surprising that Kubrick himself didn’t treat the substance of the movie with great care, according to the movie’s executive producer Jan Harlan:

Very often crew members asked [Kubrick], “Can you explain that to me?” And he said, “I never explain anything, I don’t understand it myself. It’s a ghost film!” You can’t imagine how much fuss was made over the big golden ballroom and the big lobby and huge windows that could never have fit into the hotel [based on the] establishing shot from outside. Any child can see that. And Stanley’s explanation was, “It’s a ghost film! Forget it!” … It’s not a movie with a serious message.

Kubrick’s adaptation of King’s novel was notably “free” and did not adhere strictly to the text, which made for a complex screenwriting process in which the status of a great many important plot resolutions were up in the air until the very end of post-production, indeed even after the movie’s release.

Anyone who’s seen the movie will remember the ending, which transitions from a lengthy chase sequence in the snowy hedge maze to a modified zoom shot that reveals the existence of Jack Torrance, played by Jack Nicholson, in a banquet decades earlier.

But the first audiences experienced a very different ending of the movie. Between those two shots was an entire scene that Kubrick cut from the movie after audiences in New York City and Los Angeles had seen it, as Lee Unkrich of The Overlook Hotel website describes:

Kubrick decided to remove the scene very shortly after the U.S. opening, dispatching assistants to excise the scene from the dozens of prints showing in Los Angeles and New York City. All known copies of the scene were reportedly destroyed, although it is rumored that one surviving copy may exist.

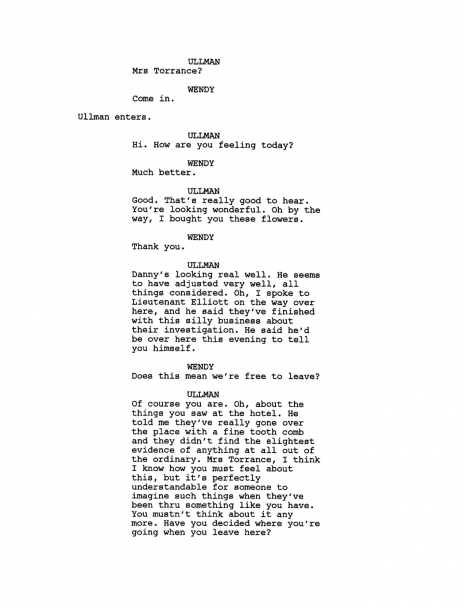

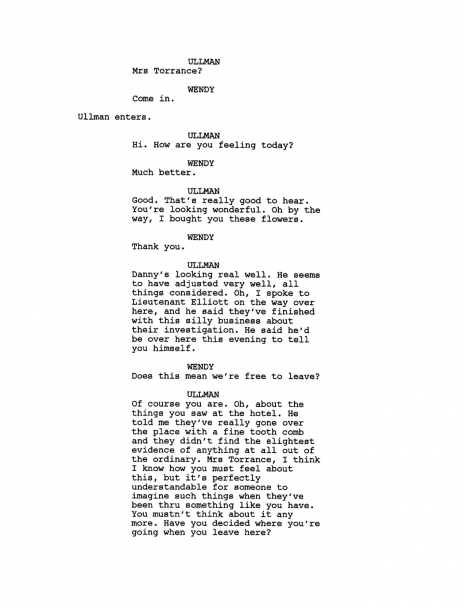

In the scene, which takes place a few weeks after the final chase, Ullman, the hotel manager we meet at the start of the movie, visits Danny and Wendy in the hospital where both are recovering. The significant thing here is that audiences get a chance to see that the two of them are OK, a reassurance denied most of the people who’ve watched the movie since then. Ullman explains to Wendy that investigators have not been able to uncover the slightest evidence of anything supernatural in the hotel. Before he leaves, according to the script, Ullman tosses Danny a “yellow ball,” presumably the same ball that was rolled to him from an unseen force outside Room 237 about halfway through the movie.

Diane Johnson, who co-wrote the movie with Kubrick, recently commented: “In other words: All of this really happened, and the magic events were actual. It was just a little twist. It was easy to jettison.”

The scene was cut on a suggestion from Warners, which felt that it was too confusing. Kubrick complied with the request. Here’s Harlan’s take:

The tennis ball is the same thing as the photograph — it’s unexplainable. It makes Ullman now another ghost element. Was he the ghost from the very beginning? The film is complex enough because nothing is explained. That non-explaining is what was bad for the film initially. It was not a huge success. Now everybody thinks it’s the best horror film ever or whatever. But when it came out the audience expected a horror film with a resolution, with an explanation. Who is the baddie? What was going on? And they were disappointed — many of them, anyway. The fact they were left puzzled was exactly what Stanley Kubrick wanted. And when the film [screened for critics] and wasn’t well received, Warners quite rightly suggested, “It’s enough, just take [the hospital scene] out.” So Stanley did it. He’s not stubborn, especially since this is a film mainly to entertain people. But Stanley was actually very sad that he misread the audience, that he trusted the audience to live with puzzles and no answers, and that they didn’t like it.

Personally, I think the scene was removed because audiences hadn’t had the first ball emphasized enough for them to realize the implications of Ullman having the same ball with him (and therefore being a ghost or something). After all, Torrance spends a lot of time throwing a ball against the banquet room wall, too. That meaning implied by the ball was too weak for the requisite “Aha!” moment to register; that would have required dialogue about the ball (“But where did the ball come from, Danny?”) or perhaps repeated instances of mysterious events related to the ball, as of way of lodging it in the audience’s memory.

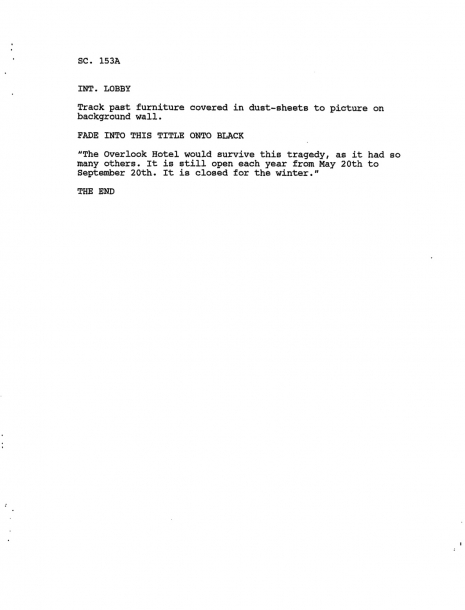

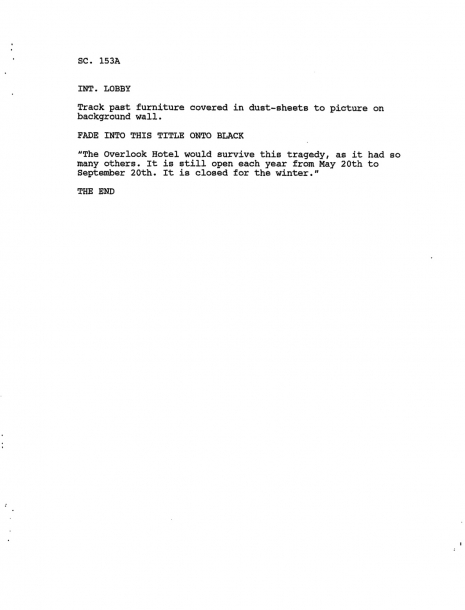

Less commented upon was the apparent inclusion, at least at the script stage, of a lame caption before the end credits:

The Overlook Hotel would survive this tragedy, as it had so many others. It is still open each year from May 20th to September 20th. It is closed for the winter.

I think all observers can agree that it was good that that isn’t in the surviving version…...

Here are the script pages for the deleted scene:

Previously on Dangerous Minds:

‘The Shining’ in the style of an 8-bit video game

Frozen ‘Jack Torrance’ from ‘The Shining’ Halloween costume

Posted by Martin Schneider

|

04.13.2017

04:04 pm

|