In 1964, Stanley Kubrick wrote to Arthur C. Clarke. He told the science fiction author he was a “a great admirer” of his books, and “had always wanted to discuss with [him] the possibility of doing the proverbial really good science-fiction movie.”

Kubrick briefly outlined his ideas:

My main interest lies along these broad areas, naturally assuming great plot and character:

The reasons for believing in the existence of intelligent extra-terrestrial life.

The impact (and perhaps even lack of impact in some quarters) such discovery would have on Earth in the near future.

A space probe with a landing and exploration of the Moon and Mars.

Clarke liked Kubrick’s suggestions. A meeting was arranged at Trader Vic’s in New York on April 22, 1964, at which Kubrick explained his interest in extraterrestrial life. He told Clarke he wanted to make a film about “Man’s relationship to the universe.”

The author offered the director a choice of six short stories—from which Kubrick picked “The Sentinel” (published as “The Sentinel of Eternity” in 1953). The story described the discovery of strange, tetrahedral artefact on the Moon. The narrator speculates the object is a “warning beacon” left by some ancient alien intelligence to signal humanity’s evolutionary advance towards space travel.

Over the next four years they worked together on the film—two of which were spent co-writing the screenplay they privately called How the Solar System Was Won.

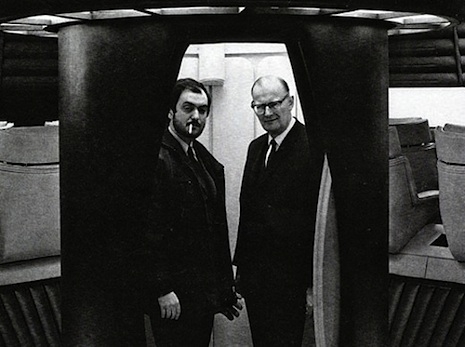

Director and Author.

Kubrick and Clarke decided to write a book together first then the screenplay. This was to be credited: “Screenplay by Stanley Kubrick and Arthur C. Clarke, based on a novel by Arthur C. Clarke and Stanley Kubrick.” It turned out slightly differently as the book and screenplay were written simultaneously. While Kubrick made the film “a visual, nonverbal experience,” Clarke widened the story out, explaining many of the events Kubrick left open-ended. The director wanted to make a film that hit the audience “at an inner level of consciousness, just as music does, or painting.”

In an interview with Joseph Gelmis in 1970, Kubrick described the genesis of both the book and script:

There are a number of differences between the book and the movie. The novel, for example, attempts to explain things much more explicitly than the film does, which is inevitable in a verbal medium. The novel came about after we did a 130-page prose treatment of the film at the very outset. This initial treatment was subsequently changed in the screenplay, and the screenplay in turn was altered during the making of the film. But Arthur took all the existing material, plus an impression of some of the rushes, and wrote the novel. As a result, there’s a difference between the novel and the film…I think that the divergences between the two works are interesting.

Clarke was more direct. He wrote an explicit interpretation of the film explaining many of its themes. In particular, how the central character David Bowman ends his days in what Clarke described as a kind of living museum or zoo, where he is observed by alien life forms.

The director on a sound stage at MGM Studios, Borehamwood, England.

Kubrick was less forthcoming. Though he did share some of his thoughts on the meaning and purpose of human existence in an interview with Playboy in 1968:

The very meaninglessness of life forces man to create his own meaning. Children, of course, begin life with an untarnished sense of wonder, a capacity to experience total joy at something as simple as the greenness of a leaf; but as they grow older, the awareness of death and decay begins to impinge on their consciousness and subtly erode their joie de vivre, their idealism – and their assumption of immortality. As a child matures, he sees death and pain everywhere about him, and begins to lose faith in the ultimate goodness of man. But, if he’s reasonably strong – and lucky – he can emerge from this twilight of the soul into a rebirth of life’s elan. Both because of and in spite of his awareness of the meaninglessness of life, he can forge a fresh sense of purpose and affirmation. He may not recapture the same pure sense of wonder he was born with, but he can shape something far more enduring and sustaining. The most terrifying fact about the universe is not that it is hostile but that it is indifferent; but if we can come to terms with this indifference and accept the challenges of life within the boundaries of death – however mutable man may be able to make them – our existence as a species can have genuine meaning and fulfilment. However vast the darkness, we must supply our own light.

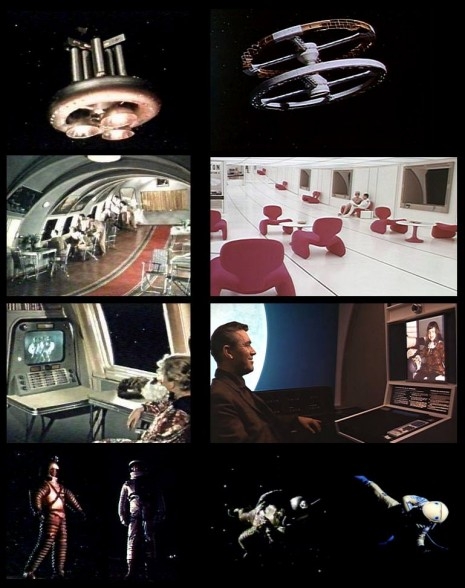

Similarities between shots and designs in ‘2001’ and Pavel Klushantsev’s ‘Road to the Stars’ (1958).

Kubrick involved himself in every aspect of the film’s production—from costume and set design, technical specifications, the requirements of specially designed cameras, to the building of a 32-ton centrifuge used to create the interior of a space craft. Kubrick was greatly influenced by Pavel Klushantsev’s Road to the Stars from 1958—and exploited many of the designs, crafts and ideas featured in that film.

During the production of 2001: A Space Odyssey, a specially commissioned short ten-minute promotional film was made that documented the intricate and exacting work involved in the movie’s creation.

Described as “a marriage of the insights of today and the knowledge of tomorrow,” 2001: A Space Odyssey was the promise of the coming century offering to:

...reveal a new and startling universe. More complex. More diverse. Richer than even today’s physicists and astronomers envision. The things that seem almost lost to our present world: strangeness, wonder, mystery, adventure—come again in space.

Previously on Dangerous Minds

Before ‘2001: A Space Odyssey’: Pavel Klushantsev’s science-fiction classic ‘Road to the Stars’

Stunning behind-the-scenes images from Stanley Kubrick’s ‘2001: A Space Odyssey’

Thank you Rupert Russell.