One of the major challenges for comix artists in our digital era has been to figure out how best to exploit the intriguing possibilities afforded by the new medium of the internet, browser comics, and so forth. Scott McCloud, author of the essential book Understanding Comics, was among the first to exploit an obvious feature of browser-based comix, namely the vertical bias imposed by the scroll bar.

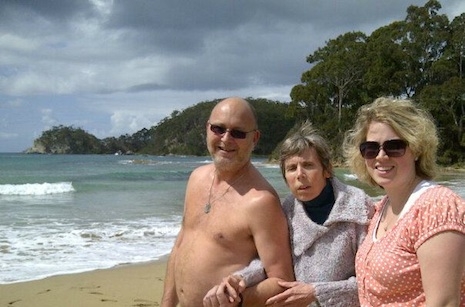

After 10 or 20 years of experiments and a good number of successes, comix artists today have established a far stronger footing in how to make the most of the browser. Case in point, Stuart Campbell’s recent work “These Memories Won’t Last,” a short web comic about the difficult final years that his grandpa endured due to problems with dementia.

There may be more to it, but “These Memories Won’t Last” exploits three aspects of online comix that the printing press could never accomplish. The first is a soundtrack, and “These Memories Won’t Last” features a subtle, almost aquatic sound design, executed by Lhasa Mencur, that features some of the aural gestalt of a dial tone mixed with a subtly creepy scene from a David Lynch movie or a flashback sequence from an immersive video game.

The second is the ability of online images to fade right before your eyes, which printed images can’t do. “These Memories Won’t Last” is about how fragile and evanescent our memories can be, and fittingly, the frames in his comic frequently fade away to the point where they are hard to make out. This ties into the third tool that online comix can use, which is scrolling. “These Memories Won’t Last” uses an ingenious scrolling convention whereby the drawn images (in blue) scroll in one direction while the captions (in red) scroll in the other direction. The two membranes slide past each other in a way that suggests a fleeting connection between the two.

More to the point, the sliding vertical motion the reader instigates by scrolling and the tendency of the images to fade actually addresses one of the most salient qualities of memory, which is that memories that are more frequently accessed tend to fade faster. (In effect, eventually you begin remembering the act of remembering rather than the original event.) So in “These Memories Won’t Last,” after you’ve moved some of the images up and down across the screen a couple of times, it starts to fade, and the more insistently you scroll to find the sweet spot where you can see it, the more it fades. (At least that was my experience with it.)

As Campbell writes, “I also had the idea that as the reader navigated through the story it would deteriorate, just like grandpa’s memories.” It’s an ingenious way to evoke the frustration of not being able to access information that translates directly to memory loss, which is after all what dementia is about.

Click here to start reading Stuart Campbell’s powerful animated narrative.

via Kill Screen

Previously on Dangerous Minds:

These photographs absolutely nail depression