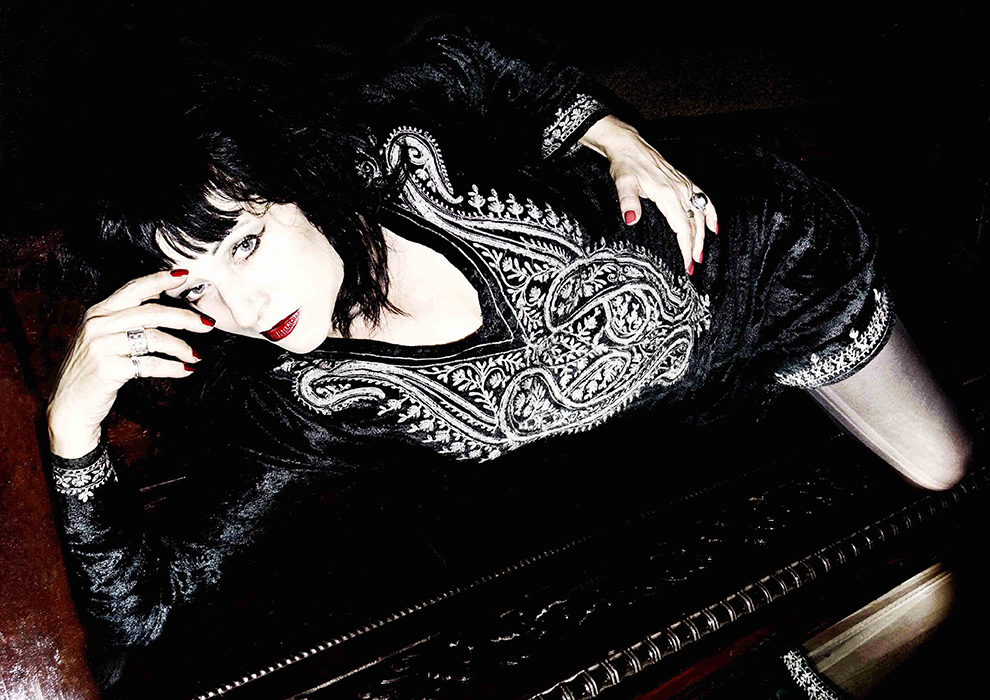

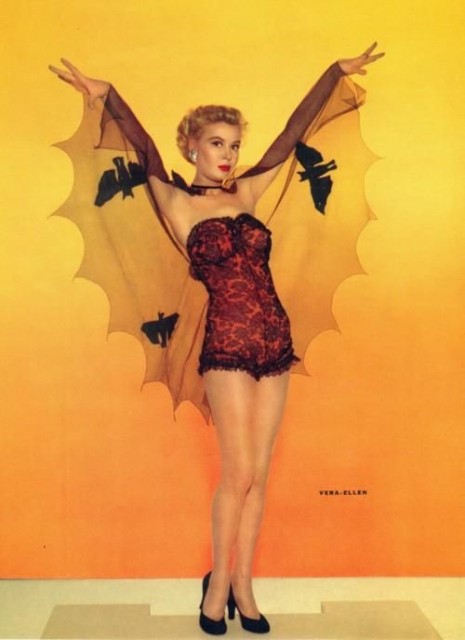

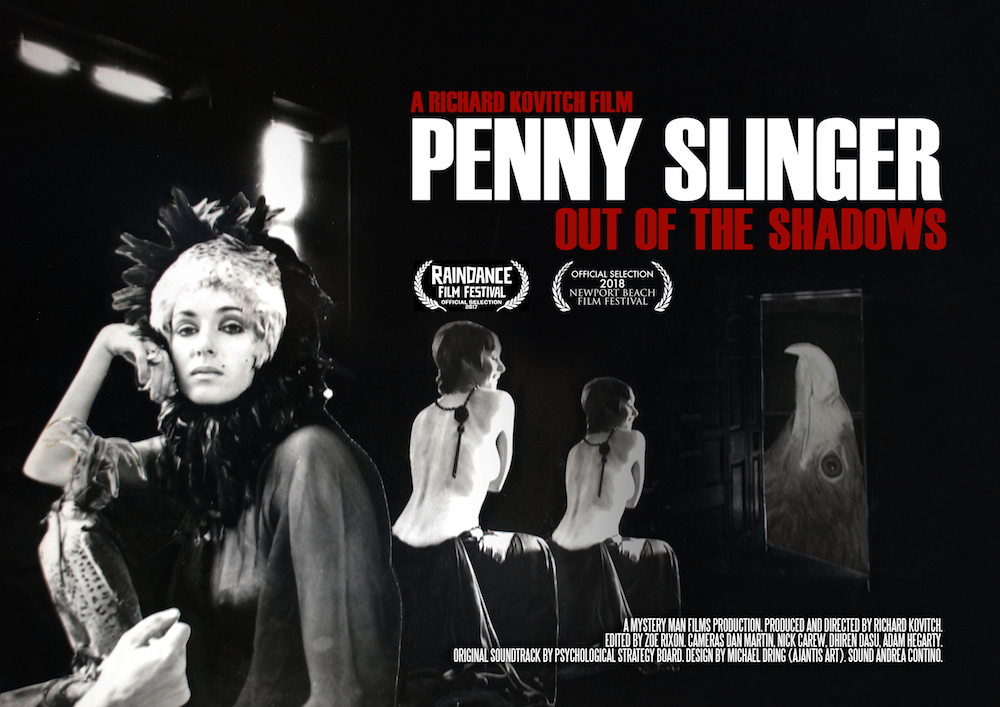

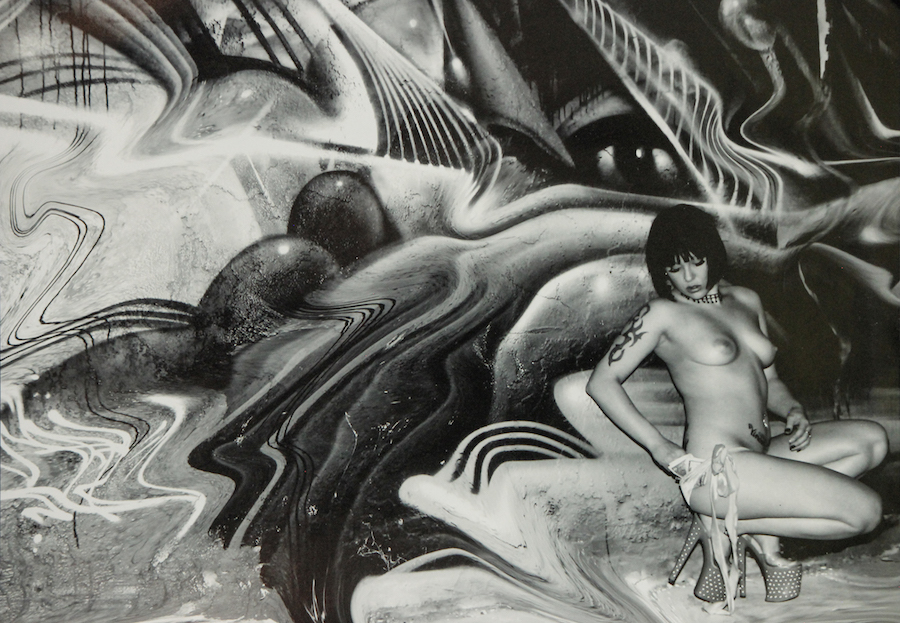

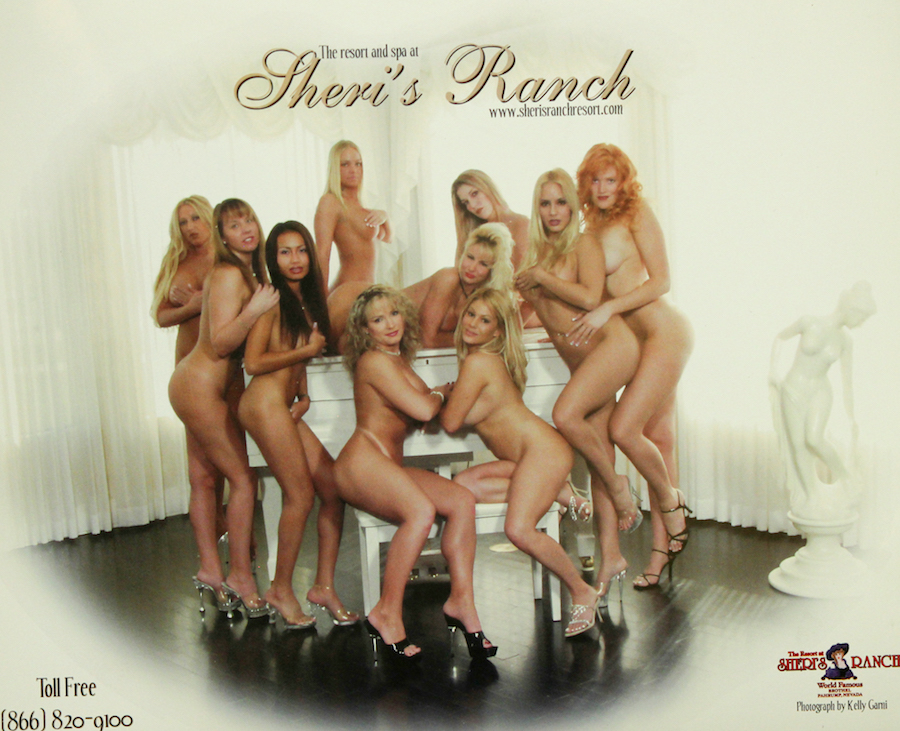

A photograph by Kelly Garni that graces the cover of his new book, ‘Naked Vegas: The Highs and Lows of A Photographers Journey’ (2022).

Kelly Garni has led a pretty storied life, his entire life. As a young teen, he became best friends with another teen, as kids do. Except Garni’s friend happened to be Randy Rhoads—a then budding guitar prodigy who would define the ultimate heavy metal sound with his instrument. Garni, who played bass, and Rhoads would go on to form Quiet Riot in the mid-70s along with vocalist Kevin Dubrow and drummer Drew Forsyth. The music put out by this original configuration of Quiet Riot is foundational, not just to heavy metal, but to glam and punk not just musically, but also in the way they dressed. Bow ties, polka dots, spandex and leather, with lots of the outfits coming from the ladies department. Their appearance created a stir at Garni and Rhoads’ high school, so much so they would routinely leave school quickly to avoid getting beat up by students who just didn’t get it. This changed once Quiet Riot started getting the attention they had worked so hard for and deserved. They were so popular, they were invited to play their high school prom even though Garni and Rhoads were barely attending classes anymore. Their classmates were no longer lining up to give them a beatdown, they were cheering for them in a swanky ballroom in Burbank. They would open for Van Halen who was coming up at the same time in Southern California. Garni’s time in Quiet Riot came to an abrupt end after an incident involving a gun and a drunken threat to kill Kevin Dubrow.

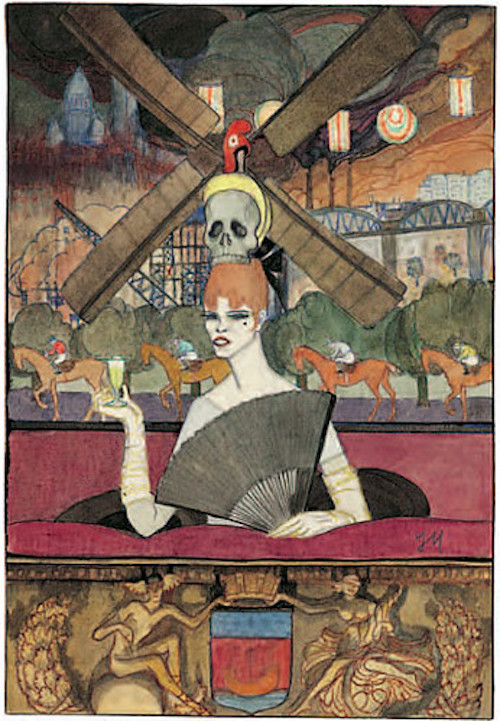

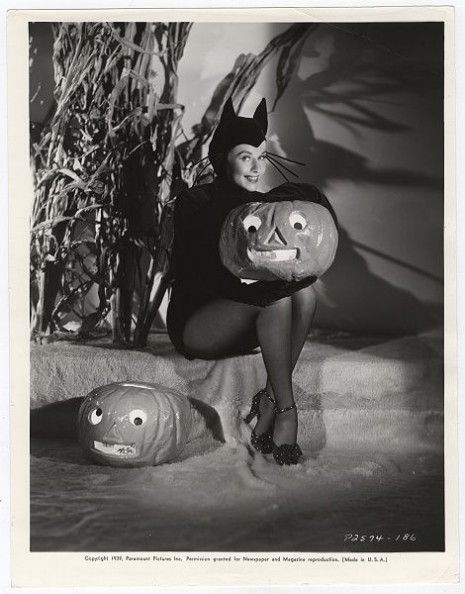

An early photo of Quiet Riot (Kelly Garni is on the left) and a ticket stub from their gig with rivals Van Halen, April 23rd, 1977. Photo by Rob Sobol. Source.

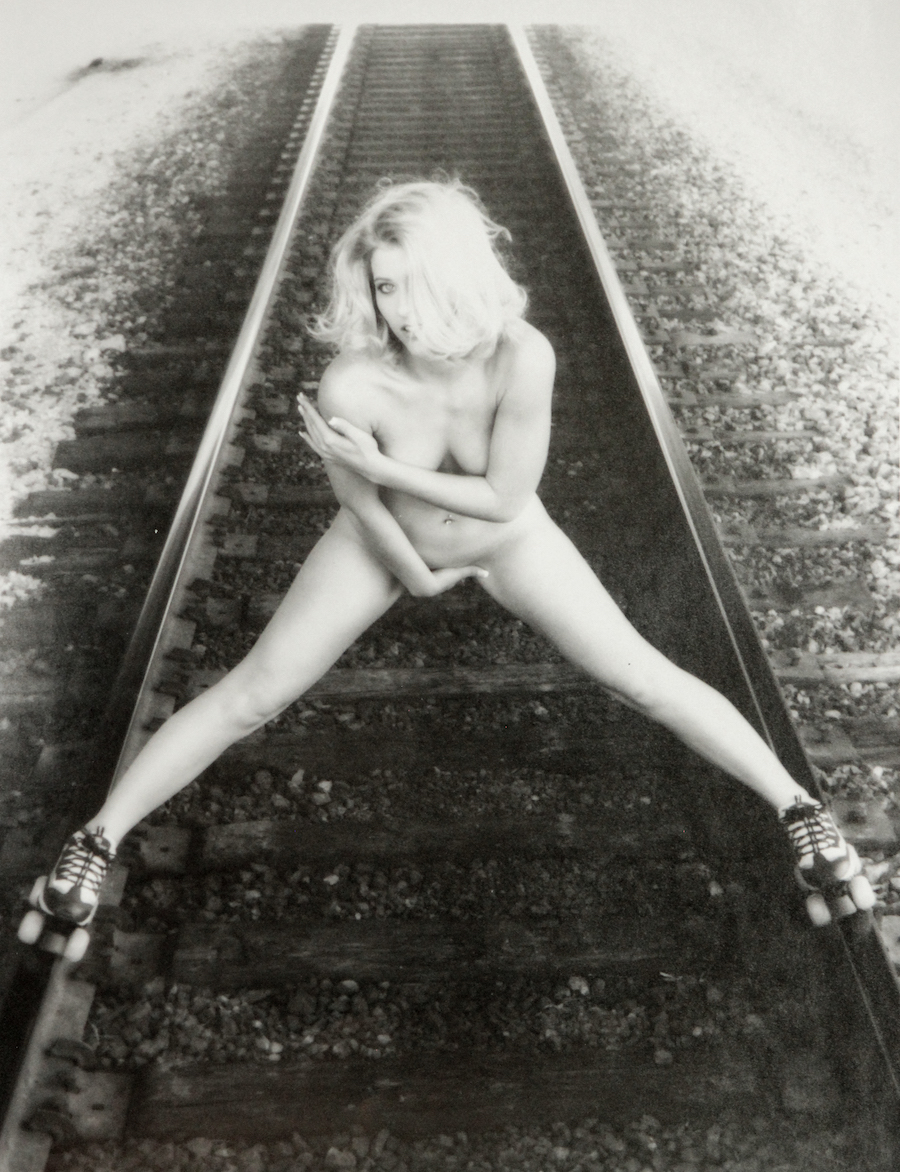

In a transitional move not unlike David Lee Roth’s in the same decade, Garni became an EMT in Los Angeles in the early 90s. As detailed in his wonderfully conversational new book Naked Vegas: The Highs and Lows of a Photographer’s Journey, he recalls the day his ambulance driver brought a 35mm camera along with her. Garni had never really used a camera and after getting some tips from his driver, he was hooked. At least until the demands of his job saving lives in LA became too time consuming, and his infatuation with photography waned. Thankfully that wouldn’t last and in the early 90s after going through what Garni describes as a very “painful divorce” he would rediscover his love of the lens. He spent time studying in the library and would chat up employees at camera stores. He built his own darkroom. Garni has never had a lack of self-confidence, and this of course worked to his advantage as he was embarking on what would become decades of photographing beautiful women merely by approaching them offering to take their photo and give it to them for free in order to hone his craft. So enthralled with the idea of photography becoming a legitimate career move, he quickly went into a bit of debt building a photography studio in his home in Las Vegas. Then Garni got the call that started it all from a modeling agency in Las Vegas that had seen some of his images. In a stroke of luck (or more likely Garni’s eye for a pretty girl), several of the girls he had recently photographed were actually working models. He would spend the next two decades taking photos of Vegas showgirls, strippers, models and sex workers, mostly in the setting of the Nevada desert. Here’s Garni on what he calls his favorite part of his life thus far:

“The next 20 years of my life (beginning in 1993) were by far my favorite. It was everything I loved. I made good money, was constantly around beautiful women, it was a non-stop party, and I was only in my early 40s. All that works for me. I had timing on my side when I started this. Timing and luck, the single greatest pairing in the history of the world for anything good that can happen to you.”

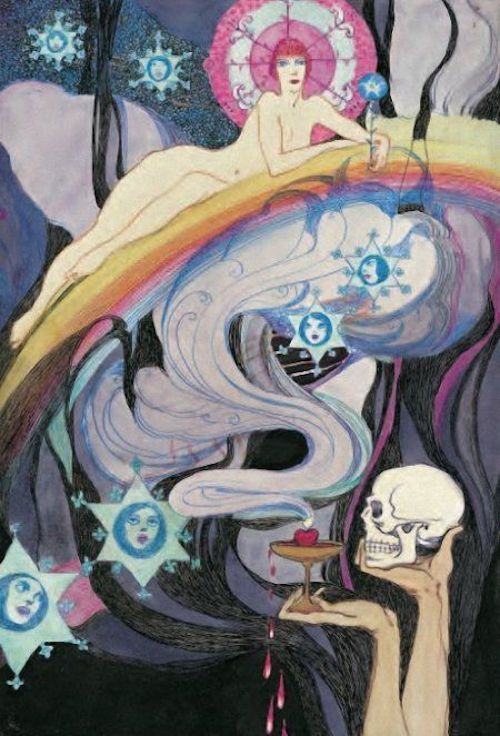

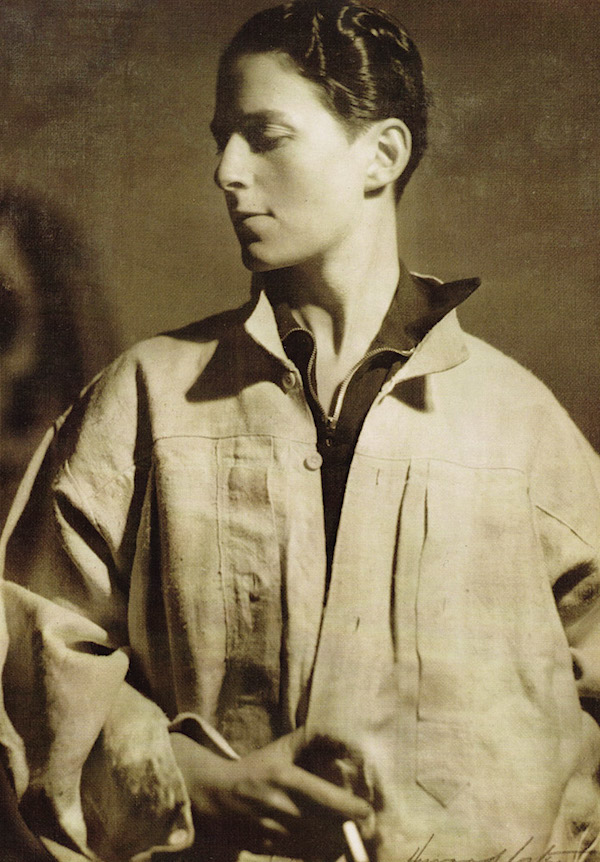

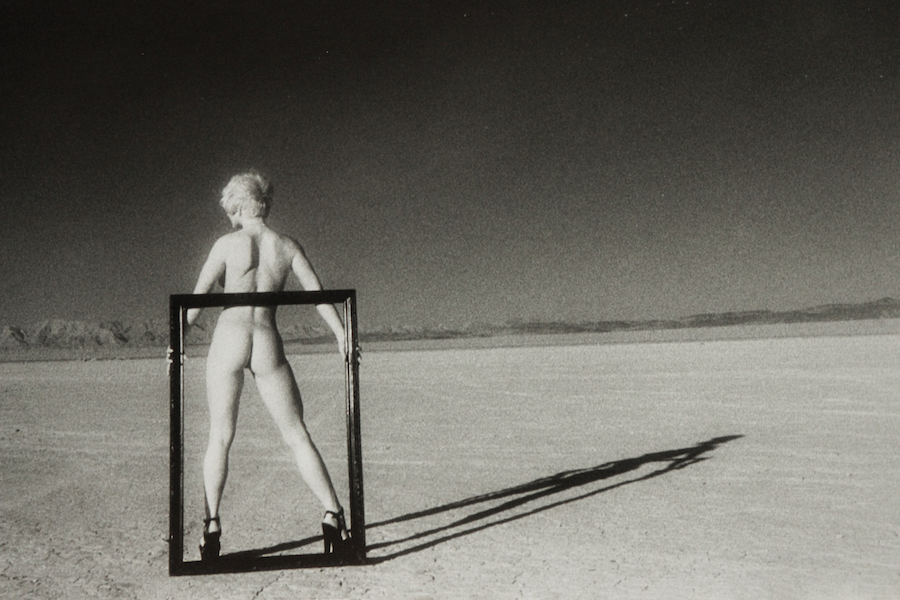

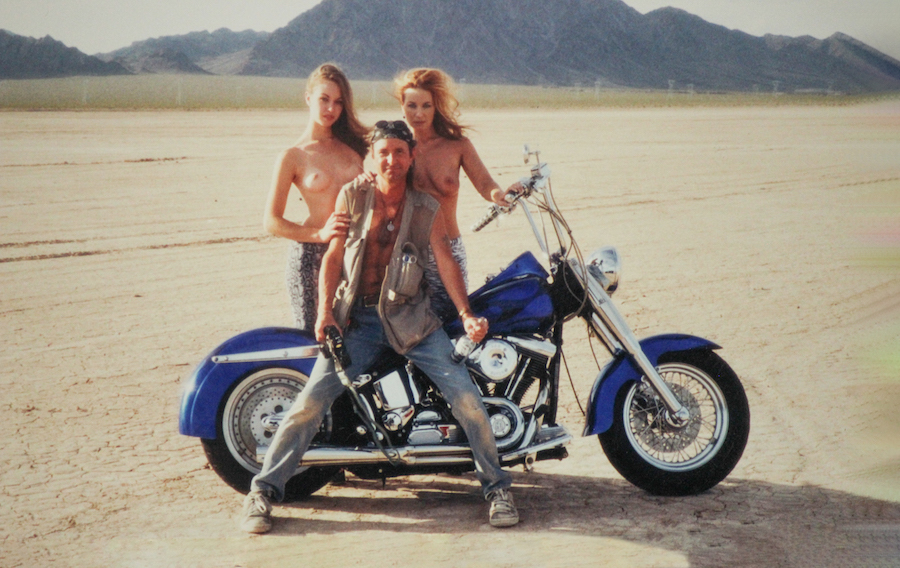

Garni getting artistic in the desert. All photos courtesy of Kelly Garni.

Garni’s assertion about this being the favorite part of his life makes sense, especially given the fact that he was living in Las Vegas during the 90s when “mega-resorts” were being built as quickly as possible. In ten years time Vegas would build massive themed “family style” resorts such as Bellagio, MGM Grand, the Luxor, Treasure Island, Mandalay Bay, the Venetian, Paris and Excalibur. Along with this, the resorts featured enormous convention facilities to help accommodate the 900 or so conventions held in the city each year. At the time, modeling agencies were making a ton of money by deploying “booth babes” to hand out company-specific merch to attendees in an effort to lure them into the all-important sales pitch from the staff inside. Garni would end up creating something called a “Zed Card” for loads of booth babes, which naturally got his images more lip-service within the Las Vegas photography industry. Though he also did other kinds of photography, demand for his nude photography soon took up 50% of his overall business. Interestingly, in his book, Garni makes it very clear that while he loves photographing women (as one should), he does not derive any kind of “enjoyment” in full-frontal nude photography as he feels it is “demeaning” to women. However, prides himself in not turning any client down, regardless of the nature of the request. Garni is a lot of things, has seen a lot of things, and has done a lot of things. Sometimes bad things (remember his desire to kill Kevin Dubrow?). But that does not make him a bad guy, and his catalog of photos in Naked Vegas convey a deep sense of admiration and respect for his subjects, even if they are buck naked. Now you might be wondering, did anything the level of “what happened in Vegas, stays in Vegas” happen to Garni during one or more of his shoots? You better believe it. And just like the debaucherous stories intertwined within the world of rock and roll, Kelly has a few shady stories about some of his clients which also reinforce his work ethic—never turn a client down. Here’s a doozy:

“Some people made this business down right creepy. This middle-aged couple came to me for pictures of a worship service at their church. They were both pastors. I guess they did alright, they had about a hundred people there donating right and left. They first asked me to do family pictures, and later, some senior pictures of their two sons. Finally, they asked about the wife doing some nudes. I thought the request was a little strange, I mean, these two were preachers. But I suppose there’s nothing wrong with a married pair of people of the fi=aith wanting some spicy pictures. Except they wanted shots that were VERY spicy. The creepy part was that during the entire shoot, the husband stood behind me. Watching. Breathing heavily. It made my skin crawl. The guy was really getting off on this. My mantra is to turn down no work no matter the nature, they became good customers in that they did these shoots several times with the husband getting more excited each time, which was always uncomfortable for me. I heard they got divorced. I don’t miss them though—they were icky to work with.”

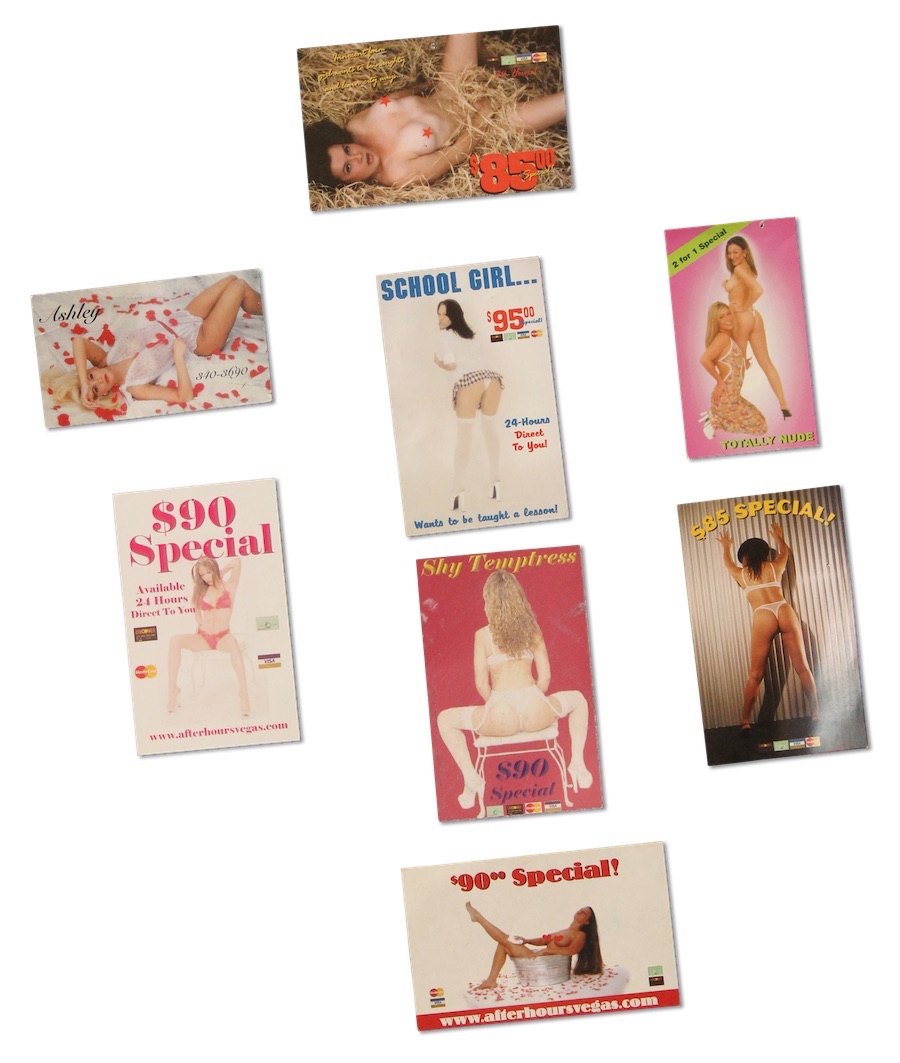

A few call girl cards featurning Garni’s photographs.

In addition to the women who worked in Vegas, Garni also did quite a lot of photography for aspiring Playboy models. And many of the images in his 153 page book are of women projecting that image. His photographs were also widely used by Vegas call girls for their business cards. If you visited Vegas during the 90s, you will remember being bombarded by people, sometimes kids, aggressively handing out fliers and cards on the strip. Most of these handouts ended up on the sidewalks of the strip itself (something I can attest to as well), creating a sidewalk plastered in photos of half-naked women with red dots on their nippples (or not). As Garni never turned any work down, he would joke that when people asked him where they could see his photographs, he said just go to the strip and “look down.” Garni spent quite a while photographing Vegas sex workers and to say he’s seen it all is an understatement. He formed friendships with many of the women he photographed and would always ask them this question; ” What’s the weirdest thing you ever had to do for a client?” As you might imagine, Garni has an arsenal of sordid tales, including one wild one about a customer the girls called “The Balloon Guy.”

“Given the number of girls who have told me about ‘the balloon guy,’ he must have spent quite a bit of time doing ‘his thing’ around Vegas. And he must also be very rich, and very old. Balloon guy would book a large suite in a major hotel. Then he would make some calls. He’d order close to a thousand balloons, small, medium and large, but not filled with helium as he wanted balloons laid on the floor. He had ‘balloon people’ spread the balloons all over the suite, covering every inch of the floor, carpet, or tile. The bathtub would be filled with water and then covered in balloons. Then the girls would arrive, strip naked and remove all their jewelry. Balloon guy was naked too, Viagra-fueled and ready to go. It was showtime. The girls were then told to sit hard on the balloons and pop them using only their bare bottoms. Hence no jewelry. Apparently, that’s cheating. Pop! Pop! Pop! He would follow them around whacking off, and then, only when the last balloon left this Earth, did he himself pop so to speak. The girls said this all took about an hour.”

The Balloon Guy sounds like he belongs somewhere in Quentin Tarantino’s character lexicon, as do some of the other stories in Naked Vegas. In it, Garni takes us along with him on his journey through Las Vegas with his eyes and lens pointed squarely on the women of Las Vegas—models, sex workers, strippers, and exotic performers, you name it. Through his photos and experience, he illuminates the some of the underbelly Vegas is known for, by navigating it himself for the first time as a self-taught photographer. Naked Vegas: The Highs and Lows of a Photographer’s Journey, is available now via Garni’s soon-to-be-redesigned website or here. Like the other images in in this post, most are NSFW. But you didn’t like that job anyway.

With many thanks to Kelly Garni and Marcy Johnson.