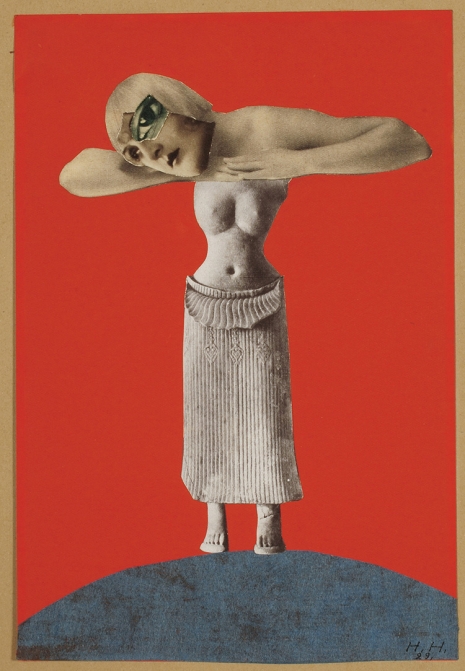

‘Untitled’ (1930).

Hannah Höch was the only female artist included in the Dada movement that flourished after the First World War. Art was then still considered mainly a man’s game—and women weren’t allowed to share the toys. Dada, however, was supposedly a radical avant garde movement that despised bourgeois conventions and the politics that had led to the carnage of the war. Though the central members of Dada’s Berlin group claimed they supported women’s rights, their words were little more than worthy platitudes as Höch was barely tolerated by some Dadaists (George Grosz and John Heartfield) who were adverse to including her work in the collective’s first exhibition in 1920. Because she was a woman, these also men expected Höch to supply the “beer and sandwiches” while they were busy discussing art and changing the world. This patriarchal sexism was all part of Höch’s long struggle to succeed as an artist.

Hannah Höch was born Anna Therese Johanne Höch into a middle-class family in Gotha, on November 1, 1889. When she first showed an early interest into art as a child, her father told her women were not meant to be artists, but were intended to be mothers and care-givers—“a girl should get married and forget about studying art.” As the eldest of five children, Höch’s role was to look after her younger siblings. When she was fifteen, she was removed from school in order to do this. Her plans for a career as an artist were put on hold until 1912 when she enrolled at the School of Applied Arts in Berlin to study glass and ceramic design. Her studies were interrupted by the First World War. Höch briefly joined the Red Cross but soon returned to Berlin where she studied graphic art at the School of the Royal Museum of Applied Arts. It was here she met the Dadaists Raoul Hausmann, with whom she had a relationship, and Kurt Schwitters, who is said to have added an “H” to her name so it became a palindrome. It was during this time that Höch began making collages. She was inspired after seeing postcards sent by German soldiers to their loved ones in which they had pasted clipped photographs of their faces over the card’s main image of cavaliers or peasants. While developing her ideas with her fellow Dadaists, Höch worked for a variety of magazines writing articles on handicraft and embroidery. This was more than just maintaining her own independence, her lover Hausmann thought Höch should work so she could support him. She described her life with Hausmann in her short story “The Painter” in which a male artist is filled with bitter resentment when his wife asks him “at least four times in four years” to wash dishes.

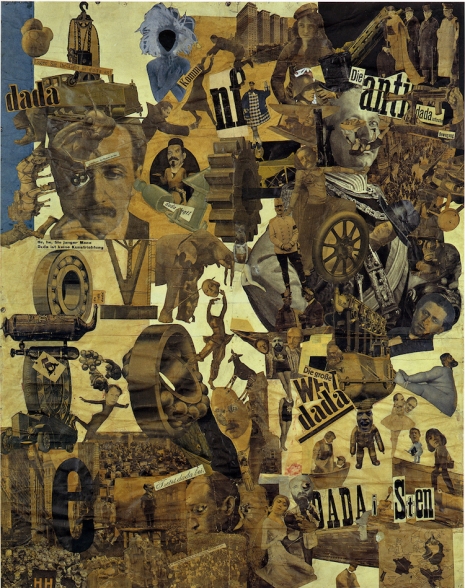

In 1920, Höch’s work was included in the First International Fair in Berlin. However, Grosz and Heartfield objected to her inclusion as she was a woman. It was only after Hausmann threatened to withdraw his own work if Höch was not included that Grosz and Heartfield relented. Höch disliked the loud, boisterous exhibitionism of her fellow Dadaists. She thought them childish and embarrassing. While their work was primarily intended to shock and cause outrage in response to the war, Höch was more interested in gender, sexism, identity, ethnicity, and society’s poisonous inequalities. She said she used photographs as a painter uses color or a poet words. In 1922, she split from Hausmann and began to move away from the Dada group. She started a lesbian relationship with the poet and writer Til Brugman, which lasted for ten years before she met and married the successful businessman Kurt Matthies in 1938.

With the rise of the Nazis in the 1930s, Höch was listed as a “degenerate artist” and a “cultural bolshevik” whose work was work was deemed to have no moral value. She spent the Second World War hidden in plain sight living an almost anonymous life in a small cottage with its overgrown garden where she continued to produce art. In 1944, she divorced from Matthies.

After the war, Höch’s work moved towards abstraction with an interest in nature and the environment. Though her work from this time until her death is less well-known, Höch was still highly prolific and never lost her desire “to show the world today as an ant sees it and tomorrow as the moon sees it.” Höch died in May 31, 1978, at the age of 88.

Höch’s work ranged from the political to the satirical. She considered the artist’s role as questioning accepted values and pushing for a fairer more equal society. Works life “Beautiful Girl” and “Made for a Party” questioned ideas about beauty, identity, and feminism, while “Heads of State” poked fun at male pomposity and the collages “From an Ethnographic Museum” examined ethnicity and racism.

‘Cut with the Kitchen Knife Through the Last Weimar Beer-Belly Cultural Epoch in Germany’ (1919).

‘The Beautiful Girl’ (1919).

More of Hannah Höch’s work, after the jump…