This is a guest post by Stephen W Parsons. Read part one of A Dark Korner in the Blues Room: A dissenting view of the ‘Founding Father of British Blues’.

By 1961 Alexis Korner had created a successful Trojan-horse musical outfit with a floating roster of talented players including Jack Bruce and Charlie Watts. In order to get plenty of work they sometimes masqueraded as a New Orleans jazz band but Korner knew which way the wind was blowing and made sure the band kept one foot in the blues.

When Brian Jones saw them play in his home town he realized that it was actually possible to play blues music and make money while doing so. He made a beeline for the suave and charismatic bandleader at an after-gig drinking session and pestered him with questions. Korner responded by inviting the young man to stay with him in London. The historical narrative is that Korner helped to create a stage character for Jones as a slide player named “Elmo Lewis” who opened shows as a solo performer and then introduced him to a couple of other blues crazy lads named Mick and Keith. He also generously donated his drummer to Brian’s new outfit: The Rolling Stones. This would all have been contemplated and planned during late night jamming sessions fuelled by hashish and vintage wine. Korner considered himself to be a connoisseur of both relaxants.

The older man had clearly seen something of himself in his young apprentice’s cultured manner and slightly shifty sense of mischief. As an amateur psychologist he must also have noticed the swarm of unresolved complexes beneath Jones’s polite veneer. Nevertheless he took the time to instruct his protégé on the subtleties of running a profitable blues band and I suspect he found it an interesting experiment. But there was a profound difference between the two men. Jones had talent, an abundance of it, and a face for the sixties. Despite a disgraceful four decades-long campaign by the remaining Rolling Stones to denigrate his abilities, both the records and surviving footage tell a different story. He also looked the business when the Glimmer Twins were still pimply young wannabees impersonating their American heroes such as Chuck Berry and Bo Diddley. In the live arena he projected a concentrated sexual atmosphere that would set young girls squirming in their seats.

No wonder the others resented him, exploited his personality defects and got rid of him at the earliest opportunity.

We now enter the thick fog of Pygmalion territory, of stewardship and responsibility, accompanied by Henry Higgins, Charles Manson, Svengali, Lermontov from The Red Shoes, and Hannibal Lecter, whose most terrible achievement was the manipulation of his psycho-analytical client roster to create other serial killers. It’s a place where nothing can be verified, only inferred, because the bond between sorcerer and apprentice is unspoken. In my own experience the best musical mentors teach mostly by example, make a few pertinent critical comments and stay well-clear of giving advice on personal matters. To step further is to invite what mind doctors call transference and unless the mentor is of sound and balanced character then this is very dangerous territory indeed.

Korner’s experiment with Jones and company was an undoubted success, but I suspect that the meteoric rise of his young acolytes actually shook him to the core. Imagine being in the right place at exactly the right time without the talent or the image to really get in the game, never mind profit from it. Condemned to be, at best, a “talismanic figure” to the real stars, sidelined and footnoted by history—always a bridesmaid never the bride.

Korner was intelligent and self-aware enough to see it all coming. The music he had preached and championed as a youthful outsider was suddenly mainstream entertainment. It was confirmed in 1964 when the Stones topped the pop charts for the first time with a slice of raw blues. “Little Red Rooster,” featuring the moaning slide guitar of Elmo Lewis, blared out from every juke box and transistor radio in the land. Overnight Alexis Korner, at 33 years of age, had become a respected veteran.

How that must have hurt.

By 1969 Brian Jones was dead in the swimming pool, but the blues explosion was continuing to reverberate. It had also cast a beneficial spotlight back on the surviving American blues legends who were finding new audiences, and better paydays, in Britain and Europe. Alexis Korner played generous host and “fun guide” to these veteran performers when they came through London. One time the Muddy Waters’ whole band spent the night at his Bayswater flat.

Domestically his reputation as the godfather of the blues scene was now under threat. It was his sole medal from the revolution he had put so much energy into and a new contender, with more musical ability, was emerging. His name was John Mayall and he had assembled a star-studded blues band that actually sold records. Jack Bruce had jumped ship from Korner’s outfit in 1965 putting his considerable talent behind Mayall and his new guitar hero, Eric Clapton, before forming the first ever supergroup: Cream.

Jack, Eric and Ginger Baker, who also had a brief stint with the Korner roadshow, took a pocket storm of dynamic blues back to America and broke every box office record as they did so. The previous arrival of British beat groups such as The Rolling Stones and The Animals had provided an interesting hybrid of pop/rhythm and blues for the US teens but nothing to match the scale and solemn intensity of Cream in full flow.

While his ex-sidemen were busy tearing up the world, Alexis Korner was still playing the same round of pubs and clubs and the hot young players were now looking elsewhere for career platforms. Mick Taylor had gravitated to Mayall’s band before moving on and up to The Rolling Stones. Fleetwood Mac with Peter Green on guitar and vocals were adding a strangely dignified lyricism to the 12 bar cannon and Jimmy Page was envisioning an outfit that would expertly blend hard rock, eastern scales and psychedelic music with the dirty soul of the blues. It would be an outfit that rendered all sterile arguments about “the real thing” totally redundant.

Korner woke up one morning and found a 15-year-old boy of mixed race sleeping on his sofa. Andy Fraser was a musical prodigy, who was already playing bass guitar in John Mayall’s band and dating Korner’s daughter Sappho. In his recent autobiography Fraser writes that Korner was ‘almost a father figure’ to him. I am sure Brian Jones would have said the same if he’d lived long enough to write a book about himself.

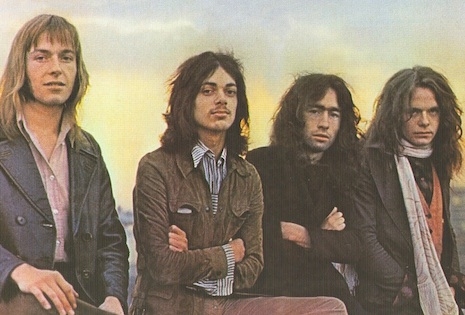

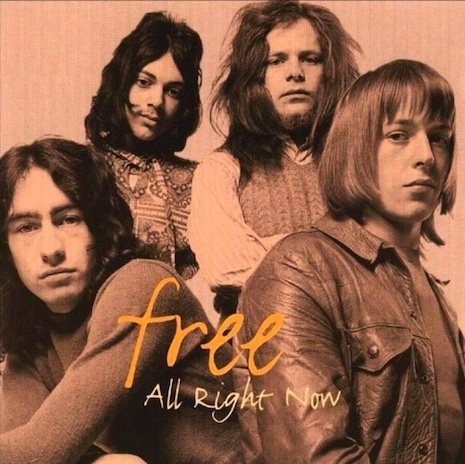

Korner took the boy under his wing and, as with Jones, introduced him to other brilliant teenage talents who had come under his tutelage: Paul Rodgers, Simon Kirk and Paul Kossoff. He blessed this outfit with the inspired band name Free. It was the Rolling Stones story all over again. The young band members were bound for glory, but like all aspects of the Korner narrative there was a curse alongside the blessing. His professional advice ladled out between fat hash joints was now tainted with a bitterness: there were “breadheads” everywhere, musicians were selling out, becoming pop stars rather than soulful players and, after Plant left him in the lurch, blaming much of the decline on the all-conquering Led Zeppelin. He was filling the impressionable young man’s head with impossible notions of purity which have troubled him, and dogged his career ever since. The kid had it all. He could compose hit songs, arrange like a musician twice his age, play piano and was a bass giant with a firm reductive style. Check out Free’s biggest hit “All Right Now,” where he has the steely nerve to lay out of the song’s verses then come thundering in with an irresistible bass line on the chorus.

Free should have been superstars, but Andy Fraser carried his Korner-nurtured demons into the Free camp. They played magnificently and fought like alley cats–broke up–reformed –broke up again and reformed without Frazer before mutating into Bad Company, which signed with Led Zeppelin’s record company and prospered. Their original guitar player Paul Kossoff didn’t live to see the good times. He died on an aeroplane from a heart attack brought on by hard drug abuse.

I first met Korner in 1973 when I sang in a band formed by Andy Fraser: The Sharks. Fraser was heavy company to say the least. I lived in his country cottage for a few months. The House of Usher must have been a more pleasant abode; long silences, abrupt mood swings and a superior air were the hallmarks of the Fraser experience. He was twenty years old at the time, a year younger than me, and acting out like an embryonic Phil Spector.

Every so often we would swing over to Korner’s London flat to pick up a block of black hash. I loathed that place. It had a fusty quality, with Korner radiantly charming at its center. He monopolized the conversation and what used to be known as “mind games” were the order of the day. Even casual, offhand remarks were loaded traps for the unwary. Kossoff was present a couple of times but in no state to chat. Korner’s two teenage sons Nico and Damien were also usually in attendance. It seemed obvious to me that the father of British Blues was keen surround himself with younger men who were easily impressed by his undoubted intelligence and ability to express himself with a sage-like clarity. I had met a few sophisticated bullshitters before so I was impervious to his cultured performance. Others didn’t seem to be so lucky.

Fraser didn’t last long with The Sharks and, despite my enormous respect for his talent, I wasn’t sorry to see him go and, as far as I was concerned, Alexis Korner went with him.

Five years later Korner reappeared in my life when, by coincidence, we were both signed to the same management company. The financial success of his unmusical activities on radio and television had mellowed him somewhat; he seemed less imposing and a little fragile. A long term combination of drink and dope will do that to a person. His musical ventures from that period to the end of his life consisted mainly of profitable European tours in a series of duos with highly talented younger players such as Peter Thorup and Colin Hogkinson.

When I sang with Ginger Baker in the 1970s, Alexis Korner played at Ginger’s 40th birthday party in a duo with Steve Marriott. Despite Marriott’s spine-tingling voice, they were sloppy and disappointing. I remember asking my own mentor, the Grand Master of Percussion, for his view on Korner and it is the pragmatic Ginger who gets the last word on the matter:

‘Musical tosser who surrounds himself with talent so he can look cool’

This is a guest post by SWP aka Snips/Stephen W Parsons/Steve, the founder of the Scorpionics self-improvement system. He sang for various beat groups until 1982 and then pursued a more successful career as a composer for hire until 2004. Since then he has voyaged into peculiar seas. His latest musical adventure is The Presence LDN which will be releasing product in October 2013. His younger, and more handsome self can be seen singing with Ginger Baker in the video below: