Scene: Opening titles.

A group of sunny So-Cal cheerleaders kick and shake: “Give it an L. Give it an I. Give an S. Give it a Zee. Give it…”

They’re going to do the whole fucking alphabet…

“...an O. Give it an M. Give it an A…”

We’ll be here all day….Jesus fucking Sanchez...

“..Give it an N. Give it an I. Give it an A.”

Wait…

“...What does it it spell…LISZTOMANIA!”

Cue Alan Whicker, for it is he…He speaks into his microphone…

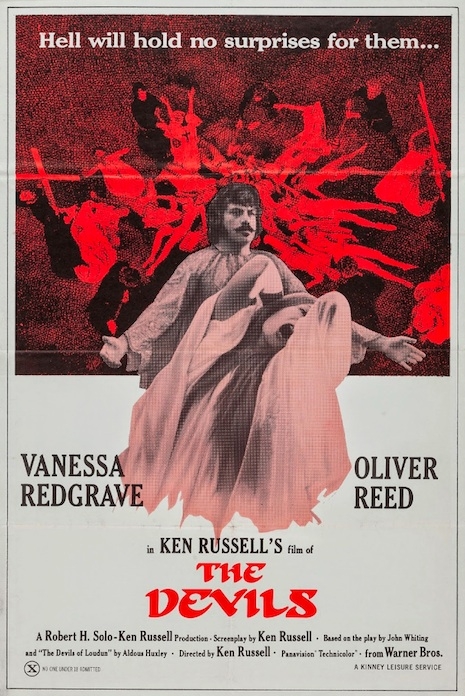

Whicker: The thing about Ken Russell’s most misunderstood and most reviled film Lisztomania is that it has some of his best stylistic devices and some of his worst artistic traits. It is a film that shows the best of Ken Russell while revealing the problems involved in ever fully realizing such a febrile imagination on a shoestring budget.

Cut to: Archive footage of producer David Puttnam in a bank vault counting money while reading movie reviews. In the background hundreds of Oompa-Loompahs are making telephone calls to very important Hollywood producers.

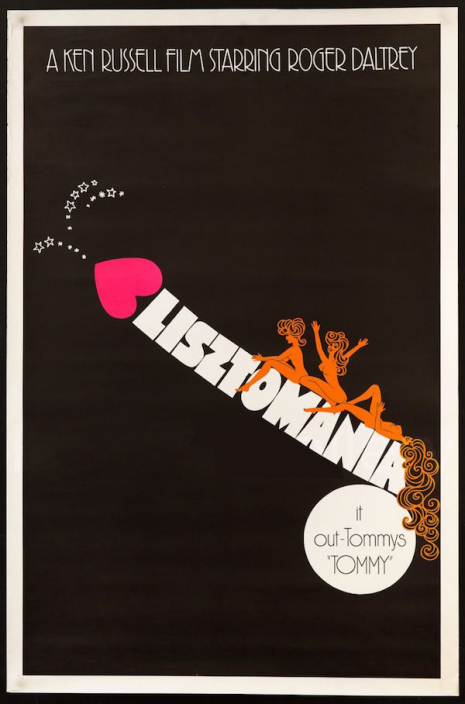

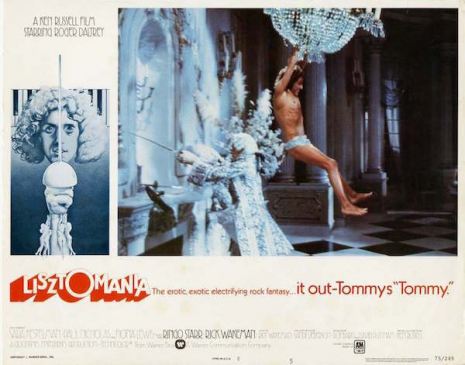

Whicker (in voice-over): This man is God. He is a movie producer. He wants to leave his fingerprint on everything he touches…Today he wants people to know he is making the Ken Russell film that will “Out-Tommy Tommy.”

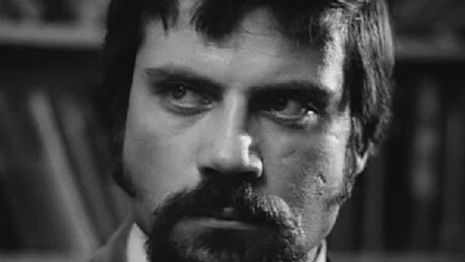

Note that David Puttnam has a beard. The writer Roald Dahl hated people who wore beards because he thought they were hiding something. Ken Russell sported a beard during Tommy. Two beards could be seen as two negatives. But as Woody Allen once noted, two negatives make a positive.

Puttnam hopes Lisztomania will be a positive.

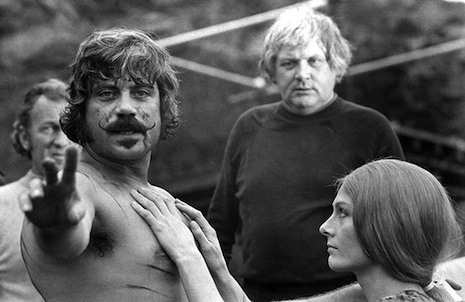

Unfortunately, Russell shaved his beard before filming and tried out a rather dapper mustache…

Suitable music, cue the blog:

Russell had originally intended to make a film about George Gershwin starring Al Pacino. He was under contract with Puttnam to make six movies on six composers. Together they’d already made Mahler starring Rober Powell and Georgina Hale to mixed reviews though some minor success at the box-office. Then came Tommy, the movie version of the Who’s classic concept album. Tommy had been a major hit with both audiences and critics across the world. Russell’s movie kick-started pop promos and whole new way of cinematic storytelling. At Puttnam’s bidding, Russell wrote two scripts. One on sex-mad classical composer Franz Liszt. One on George Gershwin. The latter was dull, The former interesting...

Scene: Exterior Day: Enter Roger Daltrey juggling fish while walking on water and turning it to wine.

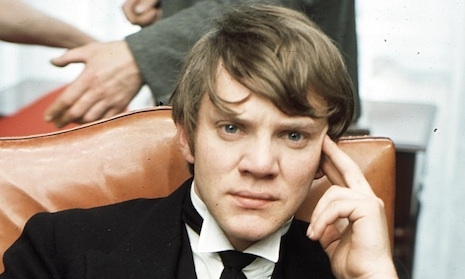

Daltrey was at his peak. He was Tommy. He was the frontman for the Who. He was the one name everyone wanted to work with. Russell wanted to make another film with Daltrey. Daltrey wanted to make another film with Russell—despite 32-takes running barefoot through a mustard field for Tommy.

Puttnam liked the idea of Daltrey and Russell making another film together. He opted for Lisztomania and dropped the idea of Pacino as Gershwin.

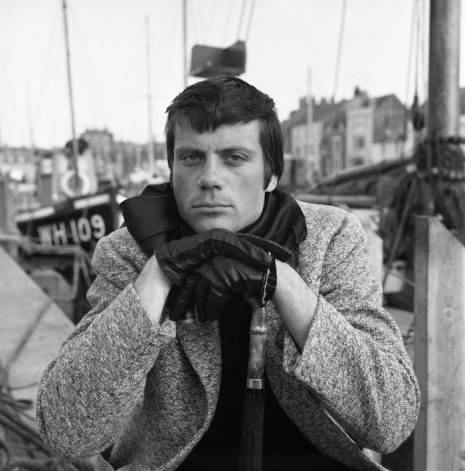

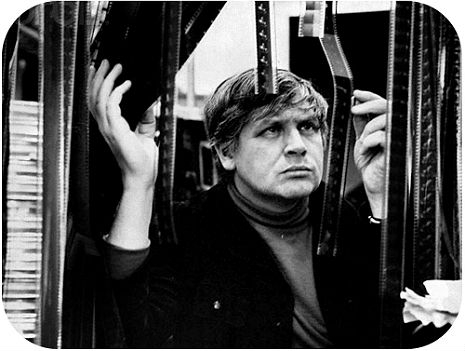

Cut to: Ext. Day: Archive footage of Ken Russell on location.

Russell: Roger is a natural, brilliant performer. He acts as he sings and the results are magical. He also has a curious quality of innocence which is why he was a perfect Tommy and why he is the only person to play Liszt.

Flashback: Roger Daltrey discusses Liszt in a TV interview from 1974.

Daltrey: Liszt’s music is just like modern day rock. He was a lot like me. He had this religious thing like me but he still went lusting after women.

Cut to Alan Whicker walking on a surf-washed beach.

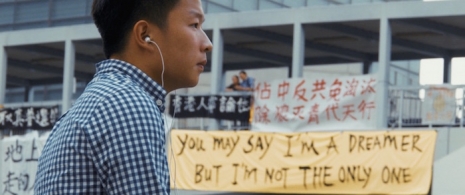

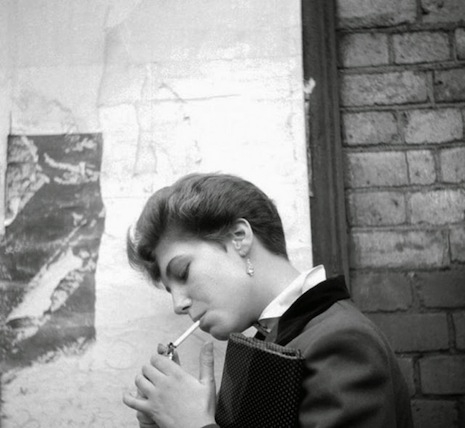

Whicker: Lisztomania was the term coined by German Romantic poet Heinrich Heine to describe the mass adulation composer Franz Liszt aroused in his fans. Liszt was mobbed by breathy young women, who swooned at his recitals, chanted his name, plundered discarded detritus for keepsakes (cigar butts, coffee cups, gloves) and dared to touch the hem of his garment.

Many Germans considered Lisztomania to be a genuine fever, but no one could find its cause or its cure. Heine later wrote:

What is the reason of this phenomenon? The solution of this question belongs to the domain of pathology rather than that of aesthetics. A physician, whose speciality is female diseases, and whom I asked to explain the magic our Liszt exerted upon the public, smiled in the strangest manner, and at the same time said all sorts of things about magnetism, galvanism, electricity, of the contagion of the close hall filled with countless wax lights and several hundred perfumed and perspiring human beings, of historical epilepsy, of the phenomenon of tickling, of musical cantharides, and other scabrous things, which, I believe have reference to the mysteries of the bona dea. Perhaps the solution of the question is not buried in such adventurous depths, but floats on a very prosaic surface. It seems to me at times that all this sorcery may be explained by the fact that no one on earth knows so well how to organize his successes, or rather their mise en scene, as our Franz Liszt.

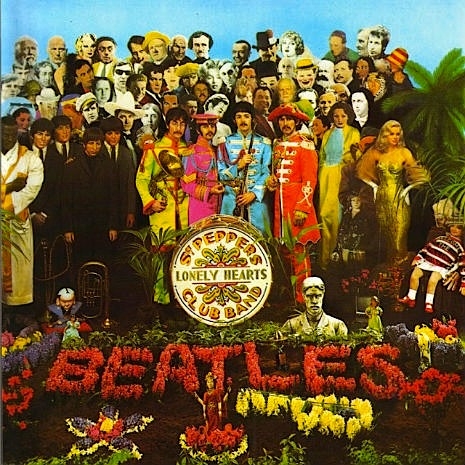

The seed was sown in Russell’s brain. Classical musicians like Liszt are the same as pop stars like Daltrey, Mick Jagger or the Beatles.

Cut to the blog:

Actually, Russell originally wanted Mick Jagger to play Liszt. However, the starting point for his script and the film was the novel Nélida by Marie d’Agoult–the “thinly disguised fictional account” of her four year affair with the long-fingered composer Liszt.

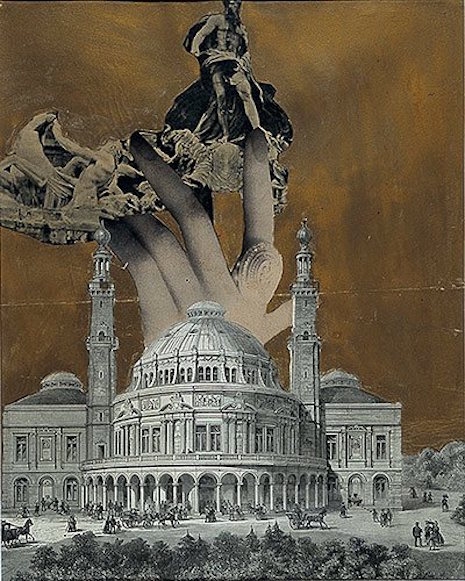

Russell saw Liszt, as Joseph Lanza notes in Phallic Frenzy: Ken Russell and His Films, as “Romanticism’s baby and the precursor to the modern pop star.”

Like other great names that caught Russell’s eye, Liszt fought internal wars. He was torn between love for his music and his prurient desires, his guilt about leading a cushy lifestyle and sitting idly during the 1849 Hungarian rebellion against the House of Hapsburg, his desperation for the kind of commercial success that would belie his artistic integrity, and most important, the queasy fact that Wagner was eclipsing him as Europe’s symphonic superstar.

Russell saw much to play with here and described Lisztomania as not a straightforward biography but coming:

...from things I feel when I listen to the music of Wagner and Liszt, and when I think about their lives.

Russell wanted to make a film about the rivalry between Liszt and Wagner, and how Wagner plagiarized some of Liszt’s work and ended up marrying Liszt’s daughter, Cosima. However, Puttnam wanted another Tommy full of rock stars and great tunes. Tommy was money. Tommy was Oscar-nominations. Puttnam liked both. But Lisztomania was an unknown quantity. Puttnam forced Ringo Starr on Russell. He added scenes and even included some musical cues that had nothing to do with anything. Russell was beginning to feel frustrated.

Sidebar: When I produced stuff for TV, I saw my job as enabling the director to bring their vision to the screen. Puttnam was of the olde school where he thought a producer had his/her vision on the screen, not so much the director. The problem with creative industries is that everyone thinks they are creative. But in truth: Producers are money and editorial. Directors and writers are talent.

Here’s another interesting piece of casting: Russell allegedly wanted Marty Feldman to play Wagner but he settled for Paul Nicholas. Not that there’s much wrong with “Cousin Kevin” Mr. Nicholas, but he ain’t Marty Feldman…

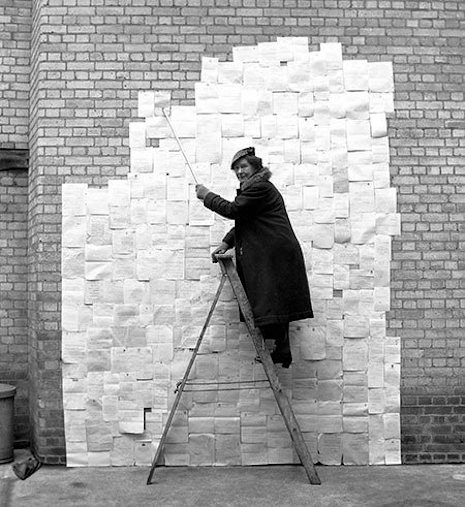

Russell’s screenplay was only 57-pages long. The script was all in his head. Puttnam insisted on having everything down on paper so he could cost it. The budget spiralled upwards but not as much as Russell wanted. What should have been Fellini became end-of-the-pier cabaret. It probably suited Russell as his imagination soared in adverse circumstances. But the different aims of a producer who wanted a pop promo; and director who wanted to make a film about art, music, and rivalry between two composers, were never fully resolved.

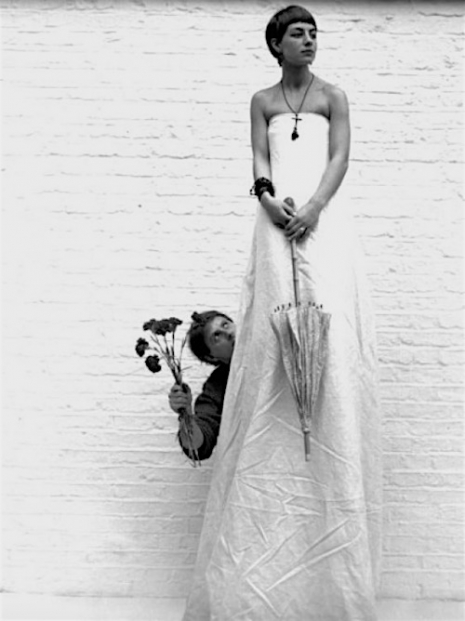

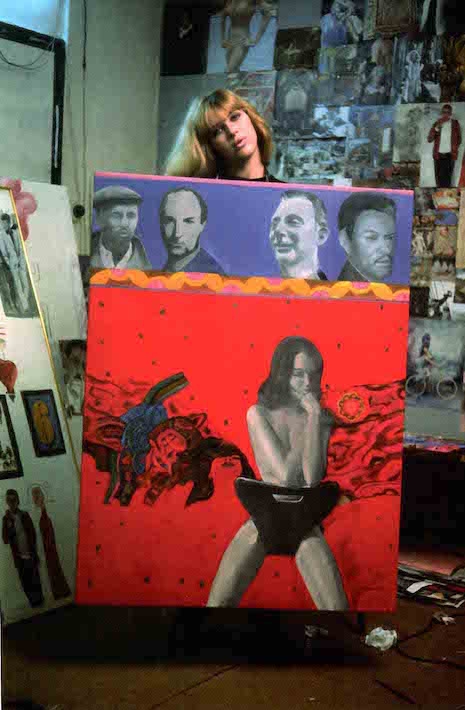

Russell fell back on the comic strip format he had used with his (banned) TV biopic on Strauss Dance of the Seven Veils. The film became a series of dreams which highlighted key moments in Liszt’s life. Russell eschewed any realism using references to Universal horror movies, pop concerts, the rise of National Socialism, mensch und übermensch, Pop Art, comedy, and even some of the movies that most influenced the young Ken Russell.

The resulting film may be considered by some as a mess, but it’s a genius mess. A film that offers up more ideas in one sequence than a dozen studio movies with one-hundred times the budget. As Ross Care correctly noted in Film Quarterly:

Ken Russell is an intuitive symbolist and fantasist, a total film-maker who orchestrates his subjects in much the same manner that a composer might transcribe a musical composition from one interpretative medium to another…

Or as Joseph Lanza wrote:

Lisztomania—[was] the film that established once and for all Ken Russell’s refusal to pay any more token favors to biographical “realism.” Lisztomania contains many relevant facts about Liszt—his music, the people who affected his life, his marital problems, his womanizing, his recourse to religion, and of course, his strained relationship with Wagner—but it goes further into the deep end than even the swastika-adorned portrait of Strauss from five years before.

Released in 1975, shortly after Tommy, Lisztomania continues Russell’s harder, more satirical edge, with more lavish sets, more crazed acting, more frenetic plot pacing, and a premise that is simultaneously silly and fantastic.

Cut to: Alan Whicker up to his next in water on a beach.

Whicker: Cinema and TV was never the same after Tommy. And Ken Russell’s career was never quite the same after Lisztomania.

End titles.

More on Ken Russell’s ‘Lisztomania’, after the jump…